I have, for years, advocated the celebration and codification of a uniquely Japanese American culture of eating that I have come to refer to as “Nisei cuisine.” Nisei cuisine is the uniquely American food that developed as the “second generation” (first to be born in the USA) of Japanese Americans, generally considered to be those born between 1915 and 1940, came of age and, post-internment, moved throughout the United States, taking part in the development of the great post-war American middle-class.

The foundation of this cuisine are the taste elements the Issei, the first generation of Japanese immigrants, brought from Japan, combined with available ingredients, both Japanese and American—essentially, Japanese flavors, sensibilities, and adapted technique collaborating with American proteins and vegetables.

Japanese Americans were engaged in mainstream communities, contributing to the development of both urban, suburban, and rural middle class American society. The formalized institutions that anchored our identity as Japanese Americans—churches, community centers, local civic organizations, local chapters of JACL—provided and reinforced cultural coherence and cohesion.

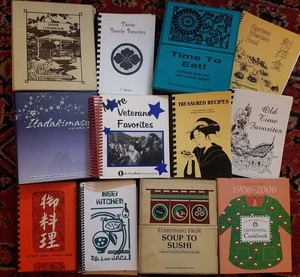

Nowhere is that sense of community more strongly manifested than in the self-published cookbooks these institutions created. The cookbooks created by these civic entities—church groups, community centers, civil service organizations, family groups, and even public institutions—serve to identify and support a community, but, as important, function to recognize that community’s history and effect its continuance.

These community sourced collections of recipes represent more than instructions on how to replicate cooked food. They are the manifestations of a tacit adherent of individuals within families, within a community, of that which makes us unique and separate from the mainstream but binds us to each other. They are mortar to the bricks of each family’s, each church’s, each civic organization’s foundation of identity within and apart from the dominant society that may—however reluctantly—have accepted our presence, but does not identify us as equal participants.

These cookbooks are the products of a uniquely Nisei experience. It was the burden of the Nisei to return the community to “normalcy” after the war. It was the obligation of the Nisei to work their way back into a full partnership with post-war American society. They left their houses every day to work in the offices, factories, laboratories, and schools among White Americans. They dressed like White Americans. They spoke like White Americans. But, when they came home, when they closed the door to the world outside, when they were surrounded by family and friends from their own community, they ate like Japanese Americans.

Today, it might be popular among us, our peers, our children, to look upon Nisei cuisine as “comfort food,” but it was, at its most prevalent, “shelter food”—repast that provides not just pleasure, sustenance, solace, and relief, but also social sanctuary and reinforcement of who we are in the face of a sustained social pressure toward conformity.

The communal authors of these cookbooks—primarily Nisei women who defined and protected the internal home—had clear awareness of the cookbooks’ ulterior mission of community preservation and perseverance.

The dedications that open these books almost universally acknowledge the recipes as a link that binds the previous generation to the next.

“From our ISSEI parents, the first generation of Japanese to live in America, we NISEI, the second generation, lovingly transmit the miracle of life and richness of heritage to our children, the SANSEI, or third generation.”

—Nisei Kitchen, St. Louis Chapter JACL, 1972

“Our biggest hope is that this book will help to provide a thread of traditional Japanese American cooking through the generations of your family.”

—Oryori Plus, Women’s Fellowship Christ Church of Chicago 1972/1993

However the food is referenced informally, within the household, the authors of these cookbooks were not passing on “Japanese food” recipes, they were clearly and knowingly interpreting, documenting, and disseminating a unique American culture across generations.

Many of these cookbooks include numerous non-“Japanese” related recipes— stroganoffs, macaroni and cheese, tuna casseroles, lasagnas, tamale pie—a compendium of multi-cultural home-making specialties of the time, straight out of the Junior League or Better Homes & Gardens. Yet, the primary category of cuisine remains a home-and-hearth version of a Japanese-based American ethnic fare.

As noted before, this is shelter food, food of the home, to nurture, comfort, and safeguard our identity from a world that does not understand, embrace, or trust us as Americans. Ethnic Japanese American food has never been well-represented in restaurants. This is food that, when available at all for commercial consumption has been most often offered in diners, luncheonettes, and bowling alleys.

The food that Nisei ate in public is well represented in these cookbooks. That fare, the sustenance of community and family celebration and gathering, is the food of Chinese restaurants of the day. Without exception, every JA community cookbook includes a collection of home versions of the Chinese food people ate at celebrations and social gatherings. Hamyu, chow mein, egg foo young, sweet and sour pork all appear in JA community cookbooks.

There are numerous reasons for the acclimation of “Chinese food”—an Americanized version of Cantonese culinary form that came to prominence throughout the United States in the 1950s and 1960s—just as the Nisei were becoming heads of households, homeowners, and parents. As the Nisei came of age, the landmark events of their lives —weddings, funerals, birthdays, organizational celebrations—necessitated venues to accommodate multi-generational gatherings. In areas where Nisei were well-concentrated, the local Chinese restaurants became major gathering places for the Japanese American community. The most famous example is the Far East Café in the heart of Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo. It became known as the social epicenter of the city’s JA community, starting in 1935 and ending in 1994, as a result of the Northridge earthquake.

Every major JA community in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s had one or two Chinese restaurants that served a similar local function. The food was cheap and different from what we ate at home. The venues promoted a culture of group dining unfamiliar to Western restaurants of the day and a social informality that allowed for variations in guest count and accommodation of multiple generations—staid seniors as well rowdy children were always well received. Most important, the owners of these venues openly welcomed their Japanese American customers. Japanese Americans could publicly celebrate the social rituals of their community in Chinese restaurants absent the curious and critical gaze of the mainstream White society.

Chinese food was becoming a mainstay of many middle class American families. Ironically, eating the Chinese food of the day was a practice the Nisei shared in common with their White counterparts. The distinction between JAs and mainstream diners in Chinese restaurants is that Japanese Americans may not have felt as comfortable in other restaurants, as did their White neighbors. And, again, in most cities with concentrated JA communities, the local Chinese restaurants went out of their way to advertise to and welcome Nisei clientele.

In Japanese homes and communities, a phrase began to be used to describe the Chinese food they came to embrace—China meshi.

So, these are the primary components of Nisei cuisine. Mid-century, further Americanized, versions of the adapted Japanese food made by Isseis, the shimmering, rambunctious China meshi of public dining and discourse, and a smattering of all-American dishes of assimilation combine to constitute a specific and unique American ethnic cuisine.

Does it matter? Immigration history and current patterns have disrupted the fixed sequence of Japanese American generational succession. The terms “Issei,” “Nisei,” “Sansei” have lost their association with specific decades. Current Japanese immigrants include well-to-do professionals and young people seeking to express themselves in ways not available in the country of their birth.

Japanese food has been embraced, internationally, by mainstream society. It is the “model minority” of foreign cuisine, embraced by the cognoscenti as pure, precise, elevated, and setting standards of excellence and artistry unmatched by other cuisines of cultures of color. White people love it and foodies go out of their way to explain to us why we should, as well.

Nisei cuisine is the opposite of Japanese food. It, like the people who created it, is unseen, unknown, and uncared about. The food, like the people, must be foreign because the face is not familiar.

But it does matter. People do care.

When chef John Nishio lovingly and painstakingly recreates the China meshi menu items of the Far East Café for community fundraisers in Los Angeles and activist and entrepreneur Julie Azuma is directing adult children of recent Japanese immigrants in making mochiko chicken for a gathering of both Japanese natives and Japanese Americans in New York City, they are not indulging in simple culinary nostalgia.

They are reminding us who we are. They are holding us accountable, requiring us to acknowledge our forebears, and sustain and bequeath to the next generation our unique identity as Japanese Americans, as did the many contributors—named and unnamed—to the community cookbooks.

Pouring gravy on rice may not be a revolutionary act, but, it is disruptive to the notion that we, as Japanese Americans, are either foreign inhabitants in our own country or fully assimilated to the culture that seeks to keep us a quiet and safe minority.

© 2017 Tamio Spiegel