Nisei Jesse Nishihata (1929-2006) was working on a TV series idea in the 1980s about the Japanese Canadian community that lived in the Powell Street area of Vancouver in pre-World War Two days. While reading Powell Street Diary, I wondered if a TV series about our community couldn’t have some success in 2017? The ingredients are certainly all there...

First: way, way back in 1942 when Vancouver’s Powell Street area was home to a thriving Japanese Canadian community (yes, we did have one) that was vibrant, colourful, and ‘exotic’. At the time, Puccini’s ‘Madame Butterfly’ opera painted a picture for Canadians about what we were, the general public had no idea what “sushi” was and Japan was fighting a war in China and were occupying Korea. Once Canada was officially at war with Japan, we Japanese Canadians immediately became “the enemy” too.

The truth was that ours was a remarkably well behaved, hardworking, and law abiding community in the midst of a very racist city. Remember: it was a time when being Japanese Canadian meant that we were legally barred from the professions, voting and employers could even pay us lower wages than our white counterparts. Racism in the political system was rampant. Isn’t this the stuff of great TV?

Now, moving the clock 75 years ahead…. those pre-WW2 kids like my own Dad, today are octogenarians. In the post-WW2 era, our community was scattered across Canada and has grown up without knowing about life in Vancouver’s Japantown. Those were certainly our glory days. (On your next trip to Vancouver, I would urge those who haven’t already done so to visit Powell Street which today is an area of derelict buildings just west of the famous Gastown tourist area. Some buildings like the Alexander Street Japanese School still survive to this day).

Jesse was a filmmaker of such noteworthy documentaries as Watari Dori and also the editor of the Nikkei Voice newspaper in Toronto in the early 1990s. Powell Street Diary was first published in Pan-Japan, Volume 1, Number 1, Spring 2000, Illinois State University and just put into book form this past summer by his son Junji who lives in Montreal.

So, a 12-year-old Jesse begins the narrative in the weeks before Pearl Harbour. The master storyteller draws the reader into a world which, though somewhat ‘normal’ from a child’s point of view, is also attuned to the drama and racism that was systematically taking the Japanese Canadian community apart even though it had done nothing wrong except be “Japanese”. Fathers were torn from families and placed into “road camps”, others into prisons at the Vancouver Immigration Building, and still others were ‘fingered’ by members of the JC community and sent to POW camps in Angler and Petawawa, Ontario with bona fide German POWs. This was the Japanese Canadian community as it was in 1942.

As Jesse tells his story, he is opens subplots like the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group (NMEG) that was meeting secretly at the Patricia Hotel and other turmoils that were occurring. Our collective histories have a myriad of intersection points and mine touched on in the book are in place names like Strawberry Hill and Shiga-ken, names like Dr. Michiko Ishii Ayukawa whose mother was a friend of my grandmother and stores like Maikawa Shoten, Frank is a good friend. Through his narrative, one hears the echoes, smells and pictures of that lost time.

As swiftly as he painted this picture, Japantown is quickly ‘deconstructed’, shutdown, obliterated in no uncertain terms: businesses closed, families herded and imprisoned in the Hastings Park barns and stalls before being sent to concentration camps in interior British Columbia ‘ghost towns’ like Greenwood, Kaslo, Sandon, Bayfarm (sic), Lemon Creek, New Denver, Slocan, and the largest, Tashme, which was prison for 2,636, including Jesse, for four years.

It has the ignonymous distinction of being named after the three vainglory and racist BC politicians who were amongst the strongest proponents of the internment: “TAylor, SHearer and MEighan”, get it?

For the most part, life before the war was pretty much the same as for any kid of that age: getting into various kinds of trouble in different areas of Powell Street, experiencing first ‘crushes’, going to Strathcona Public School, the Powell Street United Church, living in a culturally rich area at a time before Nintendo, Toyota, and anime. In today’s Canada where multiculturalism is celebrated, it is almost incomprehensible to think that we were regarded with such hatred. Thankfully, times have changed.

In 2017, Powell Street Diary is a somewhat chilling reminder about the importance of keeping Japanese Canadian stories alive or else they will become a forgotten part of Canadian history. As most of us have relatives who went through the experience of being targeted as ‘Enemy Aliens’ (the government stealing away all of our property and throwing every woman, child, and man into internment camps), there has been a certain willful amnesia on the part of Nikkei whereby we are more embarrassed than morally outraged by internment so we’d rather keep the experience quiet, another skeleton in the closet.

My own father grew up close to Powell Street on Alexander Street. Mom grew up in New Westminister. Dad’s family moved to a farm in Strawberry Hill (now Surrey). In 1942, we Nikkei had our own communities in other places too like Haney, Bowen Island, Salt Spring Island, in the Fraser Valley, even in places like Kelowna. This history must never be forgotten.

The innocence of 1942 Canada juxtaposes nicely with bittersweet goodbyes by the graduating Grade 8 Nikkei students from Strathcona, singing “Will Ye No Come Back Again” who were on their way to prison camps; friends gathered for one last time at J-town ‘soda shops’ like Sister’s Cafe where jukeboxes were loaded with the hits of the day like “Chattanooga Choo Choo” by the Andrew Sisters and Gene Autry’s “Down Mexico Way”. The young JCs seemed to take it all in stride as if this was a fate they couldn’t fight.

“Wednesday, September 30, 1942 - My first entry in Tashme! And we’ve been here already two weeks tomorrow. But let’s begin on the day we left Powell Street….” The story ends shortly hereafter as the happy-go-lucky boy who is somewhat oblivious to the chaos that many who were a little older were likely going through (e.g., how am I ever going to finish high school? What is going to happen to my dream to go to university? Separated parents were torn by worries like how to keep the family together and how to educate the kids when there were no schools?). The objective calm in the telling of this storm of events lends it clarity.

As life begins for Jesse in Tashme, BC, located outside of present day Hope, BC: “We stumble into our quarters, a tar paper home, freshly built, and we have a new address, 316 Third Avenue, Tashme, B.C. Outside, all around us, a clamour of pounding hammers and shouting men continues as the work of building a hasty town goes on....” a new chapter in the narrative for the entire Japanese Canadian community begins: separated families were trying to get back together, others chose another-kind-of-imprisonment on sugar beet farms in Manitoba like my own Dad’s family did, there were the POW stories about camps in Angler and Petawawa, Ontario where the principles of democracy failed abysmally.

It’s clear that Jesse knew that what he experienced had the makings of a great story and as a filmmaker he saw this potentially being a TV series even back in the 1980s.

As 2017 marks the 75th anniversary of internment, this book is a timely reminder of the enormity of the price that we paid simply to be people of Japanese descent living in Canada.

Jesse’s observations even as a child foreshadowed what would come in the next few years when the Canadian government did its best to rid it of the ‘Japanese problem’ once and for all by exiling us either to Japan or east of the Rockies to places like Montreal where Jesse’s settled and where Junji lives today.

As most right thinking Canadians know today, the only ‘problem’ in 1942 had to do with the racist and opportunistic politicians who used our “Japaneseness” to their advantage. It was a purely evil and invented one: a malicious setup to rid Canada of anybody of Japanese descent.

As for Jesse’s TV series idea? One can only hope that this story will one day be serialized so that we can see how life for the young Jesse unfold after those first few weeks in Tashme as was his clear intent.

This is the beginning of another great Canadian story that still needs to be told in its entirety. Jesse’s Powell Street Diary fills in a significant blank in the Canadian Nikkei experience. It is one of the most important books of its kind to be published in decades. I urge you all to read it.

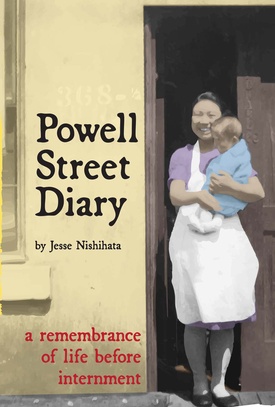

Powell Street Diary: A Remembrance of Life Before Internment

By Jesse Hideo Nishihata

(Tombo Communications, Montreal, 2017, 106 pages, $20 Canadian)

ISBN: 978-1-387-09174-4 (ebook)

ISBN: 978-1-387-05406-0

Available through Amazon.ca, Barnes and Noble, and lulu.com.

(*Editor's note: Norm interviewed Jesse Nishihata's son, Junji, in an article on Discover Nikkei.)

© 2017 Norm Ibuki