Among Japanese Americans, there are people called "Kibei" (returning Americans). They were born in America, but were educated in Japan during their childhood and then returned to America. They are called Kibei because they return to Japan once and then to America (the U.S.). In addition to referring to the person themselves, Kibei is also used as an adjective, such as "Kibei Nisei."

Most Issei men who emigrated from Japan married Japanese women and eventually had children. Many of them viewed their work in America as a kind of "work abroad," and thought that they would return to Japan once they had become successful and made a certain amount of money. They had a strong sense of being Japanese and were proud of it.

Therefore, many Issei wanted their children to learn Japanese if possible and receive an education in Japan to cultivate their Japanese spirit. In addition, because their jobs in America were too hard and they were unable to take care of their children properly, they sometimes asked their parents in Japan to look after them temporarily. Although they were a minority overall, there were some who returned to America due to their parents' circumstances, even though they were born in America and were American citizens.

After the outbreak of the Pacific War, each Japanese American had mixed feelings between two nations and cultures, but these were especially complicated for those who were both American citizens and had a Japanese mentality.

Japan and the US for one Hiroshima family

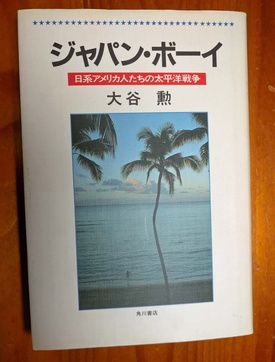

A non-fiction work that depicts the life of one of these second-generation Japanese who returned to America, spanning the period of the war, is "Japan Boy: Japanese Americans' Pacific War" (Kadokawa Shoten, 1983). The author, Otani Isao, was born in 1939. In 1979, he won the 6th Japan Non-Fiction Award for "Japanese Americans." This work was later republished under a new title, "Someone's Country, My Own Country: Records of Three Generations of the Ozaki Family of Japanese Americans" (Kadokawa Shoten).

The term "Japan Boy" refers to young people who are second generation Japanese who have returned to the U.S. One of the main characters in this book, Teruo Higashikubo, was born in Florin, California in 1918 as the second son of Aijiro and Ichiyo, who came to the U.S. from Hiroshima Prefecture to work.

Three years later, he went to Japan with his family and grew up in his father's hometown of Hiroshima, where he received his education. When he graduated from elementary school, he was invited by a neighbor's son who had just returned from the US to come to America, and he decided to go. The background to this was the harsh economic situation in Japan, and his fear of being drafted and sent to the battlefield in Japan. In any case, he went to America with the intention of returning to Japan in the future.

Teruo left his parents and was placed in the care of a Japanese farm in California, where he attended a local elementary school to learn English. The white people in his village called him a "Japan Boy." This term was used to refer to those who had returned from Japan, not pure second-generation Japanese.

As the times move towards war, Teruo, his brothers, sisters, and other Japan Boys find themselves living through the unexpected flow of time. Based on many documents, interviews, and reports, the film depicts the relationship between Japanese Americans and the war.

In particular, the book provides detailed information on the activities of the Army Intelligence Department, of which Teruo was a member, including how it dealt with Japanese prisoners of war, and how anti-American activities were carried out in Japanese-American internment camps during the war.

Win or lose, you'll get hurt

Higashikubo Teruo had one older brother, two younger brothers, and three younger sisters. Teruo was drafted into the army and entered the Japanese Language School of the US Army Intelligence Service, and after the outbreak of war was assigned to collect information for the Japanese military. His older brother also returned to the US, but after being in an internment camp he joined an anti-American youth organization. His oldest brother died of illness, and his youngest brother, who grew up in Japan, joined the Japanese military as a kamikaze special attack unit. His oldest sister spent the war in China, then returned to Hiroshima, where she witnessed the horrific scenes of the atomic bomb and was exposed to radiation herself.

After the war, Teruo was discharged from the military, but was stationed in Japan again after a while. One of the reasons was to see his parents in Hiroshima. His mother was overjoyed, but his sisters had mixed reactions.

Being in Hiroshima, where they knew about the devastation of the atomic bomb, and seeing their brother dressed in the uniform of the American military that dropped the atomic bomb, one of them said, "We felt a little guilty," while the other said, "It was a great shock." The wounds of the war had yet to heal, and Teruo, an American soldier, was not invited to a reunion with his former friends in Japan.

It is clear that at the time this book was written, vivid testimonies from many second-generation Japanese were still available. It makes you realise the great value of the words left behind by people who are now almost impossible to contact.

© 2017 Ryusuke Kawai