Luckily for us growing up in New York City, there was very little discrimination. And my dad became friends with the top godfather of the Italian mafia. I must’ve thought I was part Italian.

— Kazuo Yamaguchi

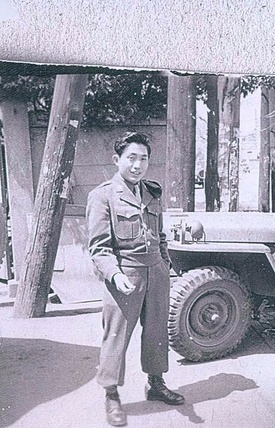

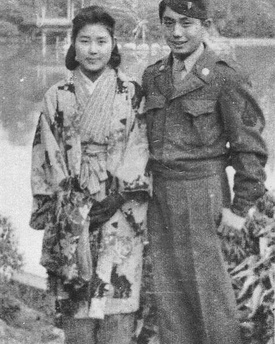

To hear Kaz Yamaguchi speak is to hear the voice of a born and bred New Yorker, complete with the “go to hell” attitude. At 92 years old and still living on the East Coast, Kaz calls himself an oddity, one of the very few Niseis drafted from New York into the Military Intelligence Service during WWII.

And how did his family get all the way over there from Japan? His maternal grandfather was a stowaway on a ship. Eventually, his grandfather built a successful greenhouse business for himself. “He was so good at it that by the ’40s by our standards today, he was a millionaire. He was very, very lucky.” Kaz followed suit and majored in horticulture, knowing more about the subject than his professors.

The war interrupted his career but he would go on to open his own business on Long Island, growing ornamental plants. “It really felt good,” he says. “Basically, I was dealing with all hakujins. There weren’t too many of us Japanese in New York who were in the greenhouse business.”

Though 75 years have past, Kaz’s wartime memories from the occupation in Tokyo are a point of distress for him: He still deals with PTSD. Despite this, he continues to volunteer at the Veterans Affairs office, giving visitors at rare—and special—opportunity to hear from his firsthand experience. I started by asking how his family planted roots in New York. (In Queens, to be exact).

* * * * *

How did your family end up in New York?

My grandfather came from Japan and they were from Fukuoka-ken. He was one of five brothers but the youngest. And he knew that if he stayed there he’d become a slave working for his oldest brothers. So he said, ‘The hell with this.’ He took a chance and stowed away on an American freighter and when he got to New York, he jumped ship.

Wow, so he actually was a stowaway. And he went alone?

Yep. All alone.

What did he do after that?

He hired himself out, working here and there. And finally ended up going into the flower business. And from there he was so good at it that in the 1940s, by our standards, he was a millionaire. He was very, very lucky.

How was it growing up in New York City? Was there any anti-Asian sentiment?

Luckily for us growing up in New York City, there was very little discrimination. And my dad became friends with the top godfather of the Italian mafia. He got to be friends with the Don, the head of the Italian mafia. And me and this Italian American kid became good friends. He became the counselor for John Gotti. In a way I guess growing up, I must’ve thought I was part Italian [laughs].

Were your parents traditional Japanese?

Very, very traditional. My father insisted on speaking only in Japanese when we were home. I look back now and think I was very lucky because I became bilingual. Think about it: A Nisei kid growing up in Queens in 1930s, all the people around us were white, and people who were very close to us were German. Other friends of mine were Italian Americans. And this good friend of mine, he was part of the mafia. I didn’t think anything of the mafia, it was a little odd.

Looking back it seemed like people were looking out of you. You had some community.

Frankly, Ellis Island was a detention center for so-called enemy aliens. And it turns out that my grandfather, because he was a Japanese community leader, was put into Ellis Island. And when my dad told his mafia friends, my grandfather was out the next day. Doesn’t that show how powerful the Italian mafia were? It’s really interesting.

Yes, it’s fascinating.

We had a very small Japanese American community. And especially since my grandfather was in the greenhouse business and was successful, I guess he would be considered a millionaire. And then when they drafted his grandson [Kaz], for him it was very puzzling. He said, ‘Why are they drafting Japanese Americans when we’re at war with Japan?’ Back then, the government didn’t know what to do with Nisei. I never saw so many Japanese American guys in my life when they sent me down for basic training.

Did you have any Japanese friends at all while you were growing up?

When I was sent down to take my basic training, I was the only New Yorker. And I thought to myself, ‘What the hell am I doing in a segregated unit?’ I must’ve thought I was Italian. I was offended I was put into a segregated unit but those other Niseis from the camps and from Hawai’i, they straightened me out real quick.

How so?

Well, without my realizing, I had an attitude. I didn’t think I was Japanese. So one day we’re on the force marching and our break was over and they said, ‘Lets go.’ I told the guys, ‘No I’m not going, I’m going to wait for the meat wagon.’ Before I knew it there was a bunch of Niseis around me and they’re telling me, ‘Get up Yamaguchi, or we’re going to kick the crap out of you.’ And I thought, what the hell are they talking about?’ Here I am in a segregated unit and we’re all Japs and now they’re picking on me because I’m a New Yorker. I didn’t realize I had a New Yorker attitude. Then when they told me the story about internment, I go holy mackerel. I was really amazed. I guess I must’ve thought I was Italian.

It’s funny that you grew up bilingual and spoke Japanese but that didn’t seem to apply to your identity. You just lived as a New Yorker.

Those Niseis from the coast, from the camps, and from Hawai’i, they taught me what it means to be a Japanese American. I guess I got the pride from being a Japanese American because I was exposed to all the Niseis and nobody had to tell me, ‘Hey, Yamaguchi, straighten out.’ And when basic training was over, I thought I was going to go to Europe. But the captain told me that was going to the MIS–Military Intelligence Service Japanese language school. They’re going to teach you all about Japan, all about the Japanese, how to read and write Japanese.

Why was Europe where you wanted to go instead of Japan?

I guess I was thinking that I was white. And I was insulted that they were going to send me to learn all about the Japanese. But they told me that I go where the army wants me to go. But maybe that saved my life because I was gung-ho. If I had gone with the 442nd, probably would’ve been one of those Niseis that said, ‘Banzai, let’s go after the Germans.’ I would’ve been killed because I was naively stupid.

What surprised you most about learning about the camps?

When I heard those guys who were from the camps, I said, ‘Hey, some of you guys actually volunteered? If I was put into camp like you guys were, I would’ve told the army and country go to hell.’ I would’ve been a no-no boy. But they taught me what pride meant. They taught me what it meant to be a Nisei. And when I ended up in the Philippines and eventually in the occupation, I know if it wasn’t for us MIS, the occupation of Japan would’ve been terrible.

Nagasaki and Hiroshima was bad but what we did in fire bombing Tokyo and a hundred other cities, it was terrible what we did to them. There were little kids wandering around. They didn’t know who their parents were, they had no parents. Their clothes were rags and we tried to bring them into our place where we lived and then we would sneak extra food out of the dining hall. The boss said, ‘No, no do not give aid and comfort to the enemy.’ All of us said, ‘Go to hell. Kids are not our enemy.’ God, those were terrible days. People dying all over the street. It was getting cold and these kids were wearing rags. God, that was terrible.

What else do you remember having to do during the occupation?

Well since I was a lot different than the West Coast and Hawaiian boys, not growing up in a Japanese ghetto but with all the white people, I guess somehow they sensed that I didn’t take a backseat in dealing with the white GIs. There were a number of times I had to tell even officers, ‘Go to hell.’ When they found out I was MIS, they just backed off. Because MacArthur told the occupation that these Niseis are very, very important.

It was really interesting and if it wasn’t for the Niseis, the occupation in Japan would’ve been a horror like it was in Germany. It was really interesting to see how important we were to be the bridge between the Americans and the Japanese people. MacArthur made certain that the occupying forces understood to not give the Niseis a hard time. And one of his chief advisors was a Kibei Nisei named Tagami, and he was an excellent guy.

How did your parents react to being drafted?

When I think about it, it must’ve hurt my father very deeply when he heard that his only son was going to fight the Japanese. It had to be hard for him. The one thing he said was, ‘Son, don’t be a coward or be a traitor. Never bring shame to our name.’ And that’s all he said.

In Japan, we took over the old NYK (Nippon Yusen Kaisha) Shipping Company right near the main Tokyo station. I think it must’ve been 3,000 of us there. And again, from there we were assigned to all parts of Japan. For some reason they kept me in Tokyo. They assigned most of us in teams of four or five. When they captured Japanese soldiers who spoke in dialect, they really needed us Niseis there. It was an interesting job and no matter where we went, there were Japanese who were very suspicious of us. What’s this Japanese face wearing an American uniform? So it was sometimes a miserable job.

What bothered the hell out of me is that later when I was asked to give a talk about the occupation, I started the have nightmares. How could I have nightmares about something that happened 70 years ago? So now, the VA hospital is treating me for post-traumatic stress syndrome. Ain’t it ironic?

I’m sorry to hear you’re still dealing with this. I’m not surprised that it still would bother you all these years later.

I guess I got the right genes from my father and my grandfather. I still have all my marbles, I think.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on May 13, 2017.

© 2017 Emiko Tsuchida