The Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 had immediate repercussions for Japanese Americans living throughout the nation—not least the Issei and Nisei civilians in Hawaii living near the naval base who were wounded by falling bombs. Amid the nationwide confusion and anger that resulted from the attack, people with Japanese faces were targeted for hostility, harassment, and insults, as well as official discrimination.

Particularly targeted were the Issei. Barred by law from naturalization, however long they had resided in the United States, they had none of the legal protections of citizenship. Even before Congress voted a Declaration of War on December 8, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526, and 2527, which transformed the entire Issei population at a stroke into enemy aliens who were subjected to a curfew, limitations on travel and freezing of bank deposits.

In the days that followed, hundreds of community leaders whose names appeared on the so-called ABC lists as potentially dangerous, were arrested and held by the Justice Department. Other individual Issei were detained or held for questioning by the FBI. Local authorities, especially in areas with long-established Japanese populations, were generally supportive or neutral. However, there were cases of negative treatment. Perhaps the most curious was that of Tsuyoshi “Mat” Matsumoto, whose wartime experience lay at the center of his many-sided life.

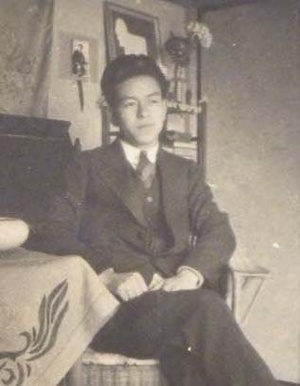

Tsuyoshi Matsumoto was born in 1908 in Hokkaido, Japan, the son of a doctor. His Christian mother sent the Matsumoto children to church. After attending Meiji Gakuin University, a missionary college in Tokyo, he arrived in the United States in 1930. There he studied at The San Francisco Theological Seminary. In 1933 he received a Bachelors of divinity and was licensed as a Presbyterian minister. He then moved to New York and enrolled at Union Theological Seminary as a theology and music major. In May 1935 he received a master’s degree in Sacred Music from Union (with a thesis on Japanese hymnology), after which he returned to Japan. Once in Japan, he distinguished himself as an anti-militarist through his public speeches on pacifism and pro-American magazine articles. Although while at Union he had expressed an intention to serve as a missionary, he forsake the pulpit for music and took work as a guest organist at Nippon Gekijo, the first theater in Tokyo with a pipe-organ. While serving as organist, he met Emiko Nakamura, a hapa ballerina and film actress ten years his junior. Emi’s Russian father Alexander Lebedeff had fled to Japan following the Bolshevik Revolution, and she had grown up there. Even as the two courted, the upsurge of militarism in Japan made life precarious for Matsumoto because of his pacifist principles.

In mid-1937, at the time of the Japanese invasion of China, Matsumoto received an urgent telegram inviting him to take a job in the United States, and sending money for his passage. When he arrived in the United States that September, however, Matsumoto discovered that there was no job waiting: the telegram had been sent by friends who feared that he would be arrested or conscripted by the militarists. After chipping in to pay his fare and provide a scholarship fund, they had sent the telegram as a part of a scheme to persuade him to leave Japan. Matsumoto accordingly enrolled at Columbia University’s Teachers College, where he remained for a year. Emiko joined him in New York. In mid-1938 he moved to California—a New World Sun article lists him in August 1938 as playing organ at a Nisei Day church service in Little Tokyo. For a time, he lived in Watsonville, where he and Emi were married and where he preached and taught music in the Japanese community. During the next years, the Matsumotos lived in Los Angeles. Tsuyoshi studied for a master’s in Asiatic Studies at University of Southern California. A 1940 census form, which lists them as boarders in a rooming house run by an elderly Swedish couple, has no employment information for either. Soon after, Emi’s passport expired, and she was forced to return to Japan. While her absence was meant to be temporary, the war intervened and the Matsumotos were separated for 8 years.

During his years in Los Angeles, Matsumoto--a rare young and bilingual Issei—bonded strongly with community elders. They commissioned him to translate “Zaibei Nihonjinshi”, a Japanese-language community history. (Actually two works are listed under his name: “History of the Resident Japanese in Southern California,” and “The Japanese in California: An Account of their Contributions to the Development of the State and their Part in Community life”). Matsumoto also worked closely with Nisei, to whom he was closer in age. For instance, in May 1940 he was the guest speaker at a Young People’s Christian Conference retreat. A year later, he directed a concert of sacred music at a Los Angeles church, with a choir of with 125 local Nisei and with soprano Tomi Kanazawa as soloist.

During this period, Matsumoto served as a columnist for the English section of Rafu Shimpo. He distinguished himself by his Christian approach to social issues and by his encouragement of Japanese American fraternization with Blacks, Chinese and Mexican Americans. He reminded his Nisei readers that as a group exposed to discrimination and exclusion they shared a great deal with African Americans. "The more I learn about colored people, the more I realize the need of closer cooperation and better understanding between them and ourselves. We have many things in common." In another column, he deplored Japanese community anti-Semitism: “Some of my most respected American friends shamelessly admit their violent anti-Jewish sentiments,” he stated. Matsumoto added that many Nisei now expressed dislike for Jews, and asserted that their unjust words made for further difficulties for Jews and other “much abused minority groups.”

In Fall 1941, Matsumoto was engaged as a music teacher at the Trinity School, an African-American school in Athens, Alabama run by the American Missionary Association (AMA). The job came at the invitation of the school’s director, Jay T. Wright, a white man who was Matsumoto’s former classmate at Union Theological Seminary. He had only been there for a short time when the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor occurred, plunging the country into war. The following day, Matsumoto was summarily arrested, taken to the Limestone County courthouse, and placed into a cage by local officials, allegedly so that people could see “what a real ‘Jap’ looked like.” He was then taken into custody at Fort McClellan, where he remained for two months. During his time in custody, he pursued his hobby of drawing, and became friendly with soldiers who would come to his cell at night to have their portraits done.

Matsumoto’s arrest led to all sorts of pressure on Wright. Ruth Morton, the AMA’s director of Community Schools, wrote Wright stating that Matsumoto’s continued presence represented “a delicate situation” for the school and requesting an immediate report on his immigration status. Another teacher wired Morton that Matsumoto’s arrest and the wild rumors spreading from it could “imperil” Trinity’s existence, and recommended an investigation to protect the school. Wright travelled to Memphis to consult the head of the AMA, General Secretary Fred E. Brownlee (who was serving as acting president of LeMoyne College). Brownlee, in turn, wrote to Matsumoto to express concern over his care and to ask if he needed reading material. This sparked a friendly correspondence between the two men. (Matsumoto wrote about the curious feeling he had being taken out by soldiers for daily walks, like a pampered dog in New York City). After undergoing a loyalty hearing by the Alien Enemy Control Board, in February 1942 Matsumoto was released from confinement, and returned to Athens. Wright later insisted that the agents left Matsumoto in Wright’s custody and warned that he was not to leave. However, upon inquiry Justice Department authorities informed Wright that Matsumoto’s release was unconditional. Nevertheless, influential locals continued to express hostility toward his presence. Following a sensational editorial in the weekly Alabama Courier newspaper, the mayor of Athens, J.C. Richardson, protested to Brownlee: “I understand that you have been informed about the Jap that is out at Trinity. That should never be, in times of war or peace. The people here resent it, both white and colored, very much. We are at a lost (sic) to understand why he ever came here and at a greater lost to understand, why he still remains.” Richardson called for Wright’s resignation. While Brownlee resisted the pressure to dismiss his employees, Matsumoto did not remain long in Alabama.

During the war years, Matsumoto worked as an instructor in Japanese language for military intelligence, first at University of Michigan and later at University of Chicago. In a pair of articles, “No Surrender at all,” in The Nation and “We Fight the Emperor,” in Asia and the Americas, Matsumoto argued that the Japanese, despite their surrender, had not abandoned their will to conquer nor their hatred of foreigners, and should still be treated as a hostile military power. In February 1946, after the Army began permitting Japanese aliens to enlist, Matsumoto signed up, and was posted as a Japanese language instructor at the Presidio Army Language School in Monterey.

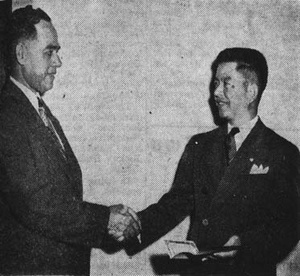

In June 1947, Matsumoto was discharged from the Army with the rank of technical sergeant, after which he was engaged as a professor of Japanese language at University of Hawaii (he was thus in the interesting position of continuing to instruct the returning 442nd and MIS veterans he had helped during the war) A year later, he was finally reunited with Emi. Meanwhile, despite his wartime service to the U.S. government, Matsumoto was faced with deportation, as his student visa had expired. Thanks to a private bill sponsored by Pennsylvania representative Francis Walter (later known for his co-sponsorship of the 1952 McCarran-Walter immigration bill) and enacted in April 1948, he was able to become a US citizen.

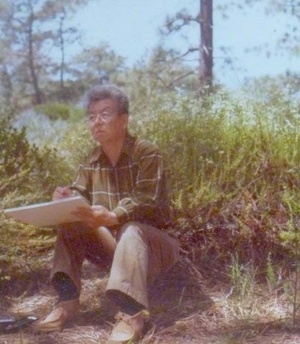

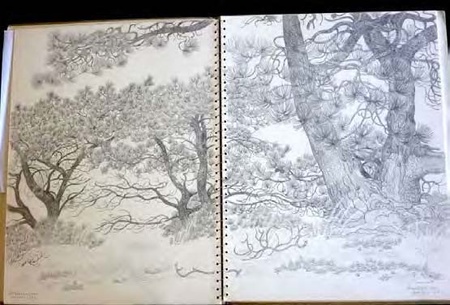

In 1950, he and Emi returned to Japan. There they spent what Matsumoto referred to as “two decades of stability,” while Matsumoto worked as Civil Relations Director at Commander Fleet Activities at Yokusuka, and studied for a doctorate at Tokyo University. Meanwhile, the couple raised two children. In 1964, Matsumoto published a book, “How to Earn Tourist Dollars,” as a guide for Japanese businessmen hoping to profit from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. During these years, Matsumoto returned to sketching, and began exhibiting at galleries around Tokyo. In 1958, a show of his abstract and expressionist art was held at the American Cultural Center in Yokohama. In particular, Matsumoto began intensive study of pines, the Japanese symbol of good luck and longevity—there was also a personal element in that “Matsumoto” means “root of the pine.”In 1968, aged 60, Matsumoto retired to pursue his art, and moved to New York, where he worked and exhibited.

In 1971, while looking for a retirement location, Matsumoto visited the Torrey Pines, a state nature reserve in La Jolla, California famous for its pine trees. According to one article in the Torey Pines newsletter, he spent hours wandering the trails at Torrey Pines and admiring the trees. In the process, he lost his wallet and keys and had to borrow money for a taxi home. In 1973 the family moved to San Diego, where they opened an art gallery in Wall St. in La Jolla. Matsumoto devoted the last decade of his life to drawing his beloved pines, spending many days at the Reserve. He filled 45 large sketchbooks with about 800 “studies of the pine”, as he called them, and he redrew many of these studies into finalized pencil drawings. He died in 1982, bequeathing his artworks to the Pines. In 2017, with assistance from Matsumoto’s daughter Helen Kagan, an exhibition of his art was exhibited at the Geisel Library at UC San Diego. His art, like his spirituality, remains a living legacy of the man.

© 2017 Greg Robinson