The migration over to Southeast Portland on the first day of the year is something that I will always remember. There were the times when the grass was crunchy with ice, where all we brought was a pillow to nap after the meal, and other times where some people (…I won’t out them here) were too hungover to take part in the best meal of the year. Regardless, New Year’s lunch at my grandparents place has been a constant in the years since I have been in this world.

New Year’s in Japan is the most important traditional holiday. According to Shinto beliefs, a kami (god, 神) enters the house on the first day of the new year, therefore the home must be cleaned top to bottom in order to properly welcome the guest. The kami of New Years is not to be disturbed with noise from the kitchen for the first three days of the new year, so all of the cooking needed to be done before the holiday. Most businesses would be closed the first three days of the new year and people would take time off of work. This all combined for an extremely busy Juu-Nichi Gatsu (December, 十二月), with lots of preparation for the start of the year.

The osechi-ryori (おせち料理) is the traditional meal served on New Years, and is made up of symbolic and delicious food. Most of the foods are preserved with salts, vinegars, and sugars to keep for the three days when cooking is frowned upon. Examples of these dishes include kuromame (sweetened black beans, 黒豆), kamaboko (boiled fish cake, かまぼこ), kurikinton (sweet potatoes and sweet chestnuts, 栗金とん), and ebi (prawns, えび). Each dish has its own meaning and purpose. Ebi is representative of an old person with a bent back and long hair signaling a long life. The characters for “kinton” (金とん) in “kurikinton” literally mean “group of gold” for a wish for lots of wealth and financial gains. Food holds a dear spot in the Japanese culture, especially on the most important holiday.

The Inahara Tradition

When it came to the Inahara Japanese New Year’s lunch, it was not as traditional as above. Myself being a yonsei (4th generation Japanese American, 四世), a lot of the strict Shinto traditions gave way to more relaxed Japanese American ideals. The most traditional part of our gathering was the food itself. It also happened that my grandmother and her family were excellent tsukemono (漬物) picklers and we got to enjoy gobo, fukujinzuke, and sunomono (ごぼう, 福神漬, 酢の物). The meals featured salmon (usually), ebi, lots of rice, fresh fruits, noodles (chow mein), fried chicken, and ozoni (a traditional New Year’s soup, お雑煮).

Ozoni is a clear dashi (seaweed and bonito broth, だし) soup that features mochi as the main star. Mochi has always held a very special spot in the Inahara family. My grandpa’s father was one of the larger producers of Japanese confections in the Portland area and was especially known for mochi. Mochi (餅) is a pounded rice cake, that has a chewy texture and is usually filled with sweetened bean paste.

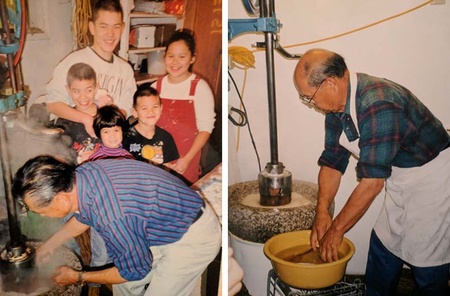

The Inahara side of my family owned a Japanese confectionery store in the 1970s in Portland. Mikado was located on 20th and SE Powell and was run by Tetsunosuke “Tets” Inahara and his wife Tei. Tets was trained in Japan as a professional confectioner and moved back from Ontario, Oregon after Public Proclimation No. 21 was announced. During the weeks building up to the new year, the family would converge and help turn 200 pounds of cooked rice into the delicious New Year’s treat. The mochi would make its way into 20-30 pound banana boxes and then to the local Buddhist churches that would prepare and feed it to their members.

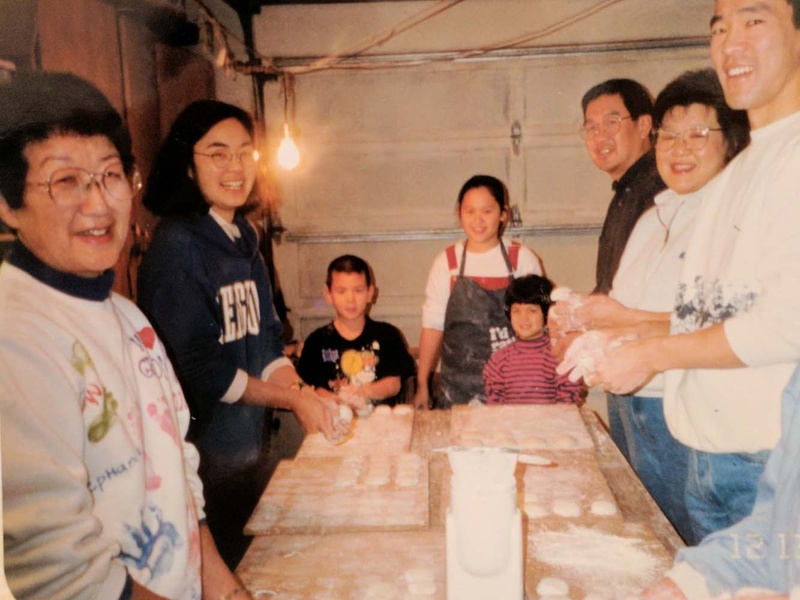

After the Mikado closed, the family used to gather a few weeks before the New Years and spend the day making mochi. The process was more industrialized than the traditional manual hammer method thanks to a large machine that provided the manpower. About 20–25 of us would get together and watch as the older men would work in the machine, flipping the rice and wetting the mallet between each downfall of the large wooden block. Once a giant mochi ball had been formed we would split the 25 pound rice ball into smaller, individual-sized balls and start shaping them. The end result was an obscene amount of mochi, clothes covered in cornstarch, and a belly full of the delicious treat.

[Right] Grandpa Yosh making mochi

As it happens, I have moved away from my hometown and the trip to Southeast Portland is much more difficult for me to make. I figured if I can’t be there then I might as well run my own New Year’s meal in Seattle. The New Year’s meal has always connected me with my Japanese family, but the invitation was extended to friends who have never experienced a Japanese New Year’s meal. Like any great meal, it brings people together from every background and cooking this meal helps to keep an important tradition alive. Just like my grandparents who grew up in a country that forcibly removed a whole population of their people based on fear, the drive to keep traditions alive was more powerful than their circumstances. I am truly humbled by their sacrifices and courage to be themselves. To put family and friends at the center of their life, to use food as a way to love and building community around tradition.

This is what Half+Half is about; navigating culture and diversity through the lens of food. I strongly believe that food has become the strongest way to identify someone. Most of the racial epithets used come from food that is commonly associated with their cultures. Within the cultures of food there is a huge amount of misunderstanding, appropriation, and distrust—and we hope to offset that here at Half+Half. In my humble opinion the most important and powerful way to love someone is to feed them. So get in the kitchen, and let’s get to work—we have a lot of love to spread.

* This article was originally published on Half+Half on January 5, 2017.

© 2017 Justin Inahara