To create the farming oasis called the Imperial Valley, in 1901 water from the Colorado River was diverted to the middle of the desert that stretches across Imperial County in the southeastern corner of California. The region is notorious for its scorching summer heat; the temperature exceeds 100 degrees Fahrenheit for more than 100 consecutive days. For a few days during the month of July, it is not uncommon for the afternoon highs to reach at least 120 degrees.

But it is the area’s warm climate that makes possible the production of fruit and vegetables during the winter season. As a result, the Imperial Valley became one of the most important agricultural regions in the country. Before global marketing, 90 percent of the fresh produce consumed in the United States during the winter months was shipped from the Imperial Valley. The area was consequently nicknamed “The Nation’s Winter Salad Bowl.”

The Imperial Valley’s winter and spring harvest season gave it a special niche in the national produce market. And the Issei pioneers deserve high praise for developing and supplying that niche market. Winter tomatoes from the Imperial Valley, for example, were highly sought after especially in northeastern cities. In 1940 an estimated 95 percent of the tomato acreage in Imperial County was cultivated by ethnic Japanese farmers, according to one government document.

Crop prices were highest when fruit and vegetables were in limited supply. Once harvesting was fully underway by all growers, prices plummeted as markets became saturated with perishable produce. It was for that reason that the produce industry was characterized as a mad race to be the first to harvest. In farmers’ parlance, the objective was to “come out” first.

In the highly volatile produce business, farmers who began picking their crops before anyone else made a killing and were the talk of the town. Under the headline, “First Squash Shipped,” the Brawley News announced on March 22, 1915, that T. Okubo harvested the first summer squash of the season and that he received five dollars for the 25-pound crate.

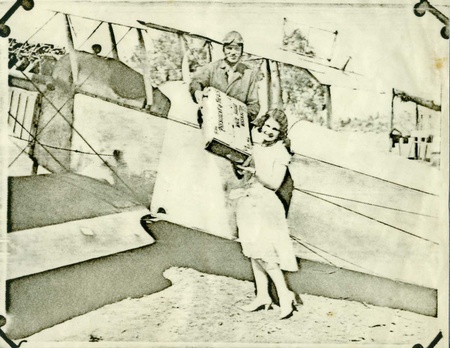

Moreover, it became a local tradition to send the first crate of cantaloupes harvested in the Imperial Valley to the president of the United States by airplane. The honor of doing so spurred fierce competition between all of the farmers and grower-shippers throughout the county. It is known that on at least two occasions, the accolades and bragging rights were earned by Issei farmers. The first cantaloupes harvested during the 1915 season were grown by Kyutaro Nakamura and shipped to President Woodrow Wilson. And in 1927, the distinction went to Kenichi Iwata who airmailed the first crate of melons via biplane to President Calvin Coolidge.

While farmers had an incentive to “come out” first, by planting early they did run the risk of losing their crops to unpredictable winter frosts. Despite the Imperial Valley’s warm climate, winter mornings could be dangerously cold.

In late January 1937 severe frosts devastated the region’s fruit and vegetables. In different parts of the Imperial Valley temperatures dropped to between 12.4 ºF and 21ºF. Even in Niland in the extreme northern part of the county, dubbed the “frost-free zone,” the temperature fell to 18.2ºF. It was reported in the Holtville Tribune that the temperature reached the lowest level in the valley’s history and caused $3 million worth of losses in the agricultural industry. Only 40 percent of the grapefruit crop had been harvested; what was left was a total loss. Cantaloupes and watermelons suffered 50 percent damage, the pea harvest was set back by a month, and 100 percent of the tomatoes and squash were completely “wiped out.”

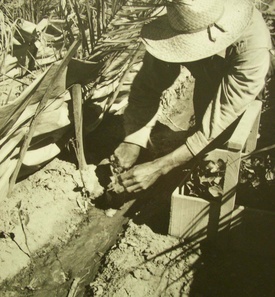

So to reduce the risk, Issei farmers came up with two farming practices called hot-capping and brush-covering. Both innovations provided some frost protection but they were primarily designed to promote early harvest by artificially generating more heat, which accelerated plant growth. The two techniques epitomize the Issei generation’s ingenuity in adapting to natural conditions to create more favorable growing conditions.

Planting crops under hot-caps or putting up brush-cover were labor intensive operations and increased the cost of production. However, crops grown under hot-caps or brush-cover could “come out” at least ten days to two weeks earlier than crops grown without either capping or covering devises, and that justified the added expense. Local farmers referred to crops as being “open” if they were not hot-capped or brush-covered, as in “open melons” or “open squash.”

Hot-capping and brush-covering were primarily used in the production of cantaloupes, tomatoes, squash, eggplant, peppers, and other frost-susceptible vegetables. Because of the cost, typically just one of the two techniques was used for a given crop. In the growing of tomatoes, brush-covering was more common than hot-capping. While in the melon industry, the use of hot-caps was the prevalent practice.

Hot-capping was reportedly invented by an Imperial Valley Issei named Abe. He took a strand of wire and hooped it over the planted seeds. A single sheet of waxed paper was then draped over the wire and the ends of the paper were buried in the soil. One hot-cap was placed over each clump of seeds so that they resembled miniature pup tents in single file along each row of a field.

Rows for vegetable crops were made so that they ran east to west. Seeds were sown on the southern slope so that the plants were always exposed to sunshine. As the plants grew, the east end of the hot-cap was opened up to allow the vines to creep out. The west end of the hot-cap was kept closed because the prevailing winds usually blew from that direction.

Brush-covering consisted of a paper wall that lined each row of a field. The paper was propped up with arrowweed brush, hence its name. Palm fronds could also be used. Wooden stakes and wire added additional support but they were also more expensive. The paper walls were erected a few inches behind the seed-line at an angle so that they leaned over the growing plants. The paper captured solar heat and increased the temperature by as much as ten degrees. It also afforded some protection to the plants from wind, which reduced wind-scarring on the fruit. Ideally, large rolls of kraft paper were purchased from local suppliers, such as the Scheniman Paper Company in El Centro. But when farmers fell on hard times, particularly during the Great Depression, they made do with old newspapers.

In describing the cantaloupe industry alone, the agriculture commissioner of Imperial County, B. A. Harrigan, declared that by 1914 “Japanese farmers dominated the field and improved methods by introducing the covering and brushing systems.” The invention of hot-capping and brush-covering is yet another example of the instrumental role that the Issei generation played in the development of Imperial Valley agriculture.

© 2017 Tim Asamen