“When we got to camp it was really nice because there were all these kids, same age. From what I can remember, it was fun. It was fun.”

-- Sandy Kaya

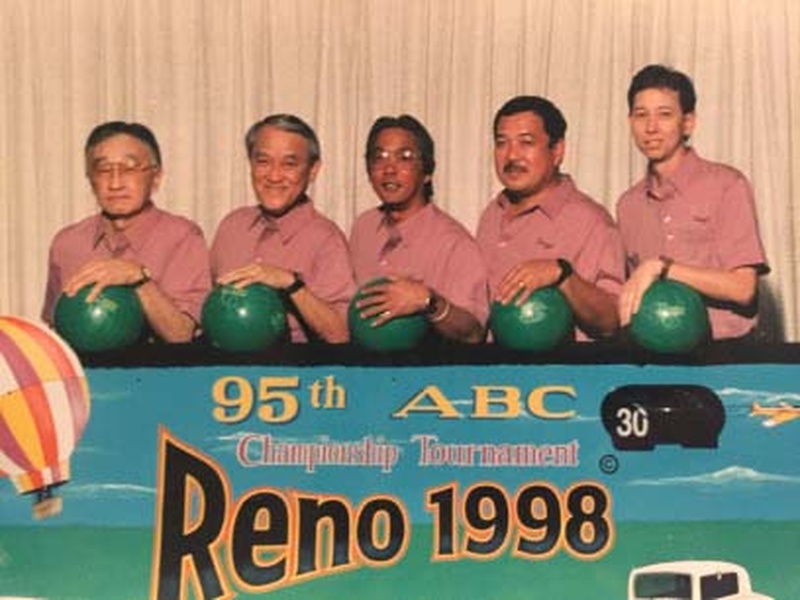

Sandy Kaya is one of my father’s oldest friends from elementary school. Soft-spoken, generous, and committed to keeping his Berkeley community of Japanese American friends and classmates in touch, Sandy is the anchor that sustains the relationships of the past. Each year he coordinates a reunion, maintains the master email list and is the group’s news anchor, telling others about the well-being of everyone else.

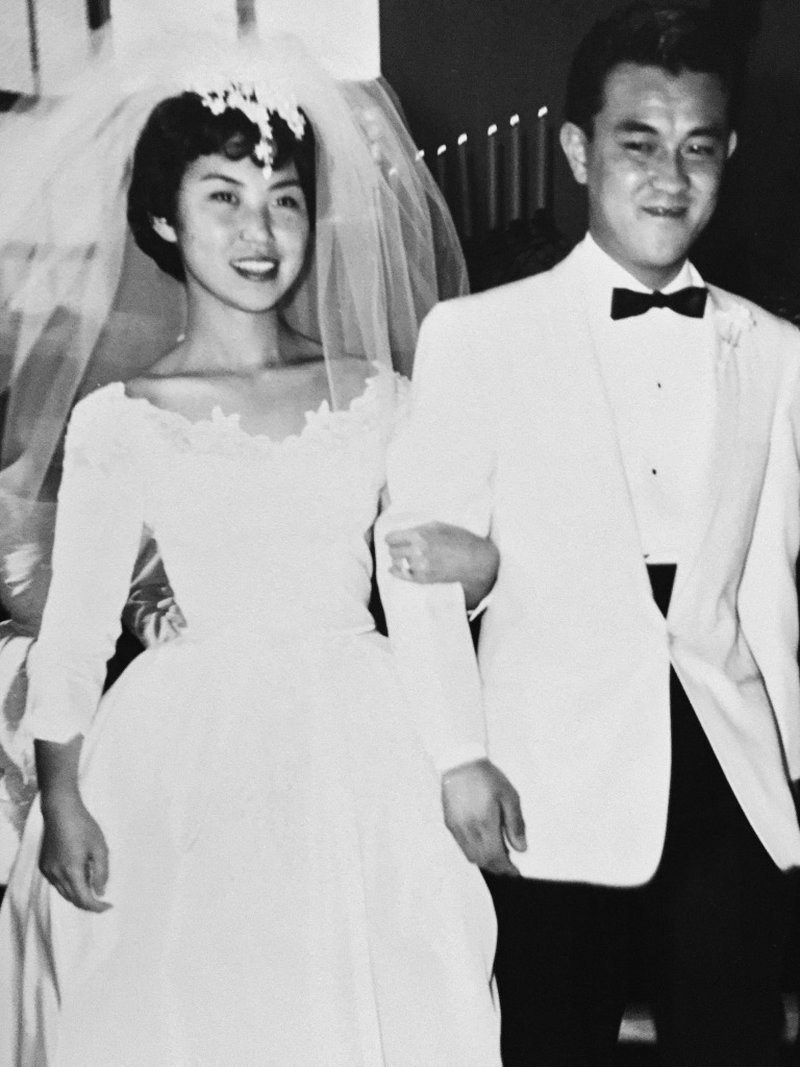

My father, an only child, remembers going over for dinners at Sandy’s boisterous house of nine brothers and sisters. Sandy would eventually marry Lois, his high school sweetheart, and when he was 25 years old, he went into the army little over two years. For the next thirty and a half years, he worked for Safeway, starting out as a produce clerk then as a clerk in the wine department for 15 years, the job that he enjoyed the most.

In his Martinez, California home, I sat down with Sandy. Lois tended to things in the kitchen as we talked. Behind him hung a photo of him from his days in the army, adorned with Hawaiian leis and peppered with well wishes and “Happy Birthdays” from friends on his 60th birthday. He is now 79.

* * * * *

Have you ever spoken to anyone about this before?

No. I went to my grandson’s high school and spoke to them. And I went to a church and spoke to the women’s group and that’s about it.

What do you remember from when you had to leave? Can you describe how you were living when the war began?

At that age I was five, I wasn’t in school yet. It was just before my fifth birthday when Pearl Harbor was bombed but I never knew it when it happened. Whatever happened at that time, my older brothers and sisters had mentioned it. At that age and not understanding anything, we were just wondering why we were moving. I remember going on a train, it was really early in the morning, bound for Turlock. We went to Turlock to go to camp there and our family being so large, we got a stable. The whole stall to ourselves. And then later on, we went to camp in Gila River. I started remembering things there. I was almost five and a half. I remember taking my sister to school, walking to school together. At first my mother took us but then she had to work.

What did she do?

She worked in the mess hall. And my father was a helper in the mess hall. And my father was born in Japan but was raised in Hawaii so he spoke pretty good English. My mother spoke very little English because she was from Japan and lived on the farm and when she came here back in 1918, once she met my father in San Francisco and they got married.

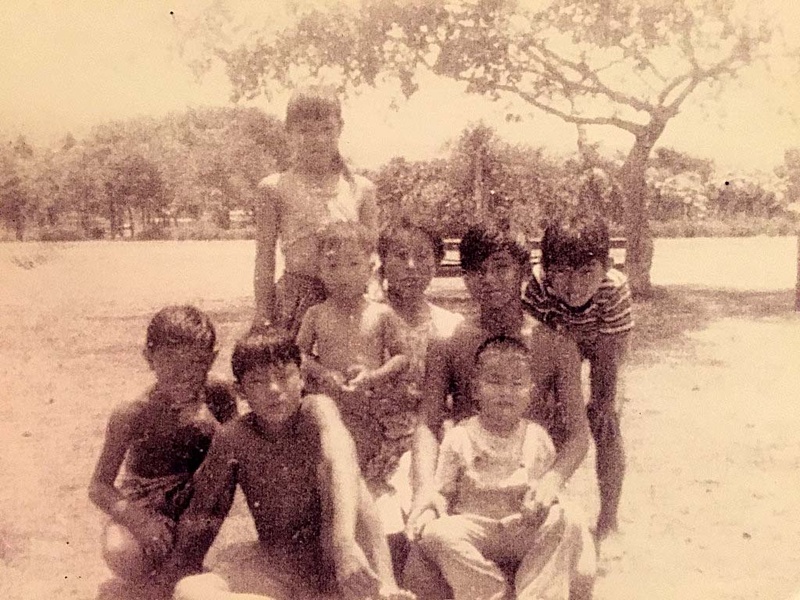

Anyway, we got to camp and being in camp, to me, was really something good because living in Lafayette where we were born, I don’t remember playing with other kids. But my older brothers and sisters used to go to the Japanese American hall in Concord and we would meet almost every Saturday night to go watch the Japanese movies.

When we got to camp it was really nice because there were all these kids the same age. From what I can remember, it was fun. It was fun. Because I knew what to look forward to when I got home. When we got back to our barracks we were going to play with the other kids.

But you didn’t have that when you were in Lafayette?

I had some nice friends, the kids on our block. And we had some that were not nice. I was too young and all we thought about was playing. Having a good time. But not knowing what my older brothers and sisters went through, later on we found out how tough it was for the older ones. Especially my parents.

That was my next question, your parents’ reaction to the camps.

All I remember was that they weren’t in the house too much because they had to work. I don’t really remember that much. The only thing that I remember was that the food in the camp, us kids didn’t care for, you know. Because we weren’t used to eating that kind of food.

What do you remember it being?

Well the spinach, we used to eat, it was the crushed spinach and the crushed carrots. You know, it was just like eating baby food. I just didn’t like the flavor, as I grew older I just didn’t like the flavor of those.

Are those things you still don’t care for?

Spinach and carrots, yeah. When it’s crushed. But my dad later on, this is what he used to tell us in junior high school. He would say, “You know the only good thing [about camp] for our family was we had a roof over our head.” Which we did have in Lafayette but [in camp] we had three square meals a day. Whereas when we were younger growing up, my father would say, “Yeah well, we couldn’t eat too much.” He couldn’t provide. Couldn’t go out and buy a lot of things. My father said they would go hunting for squirrels, possum, whatever they could get. And that was put on the table. And I didn’t know what they were eating.

Before camp, they were farmers. My mother would be out growing vegetables for us to sell at the produce market in Oakland. And after we got out of camp, my father got a job as a potato farmer in Litchfield Park, Arizona which is right outside of Glendale, Arizona. And right next to Litchfield Park, Arizona was the air force base. It wasn’t that great but it wasn’t that bad, compared to the other guys who moved back to California where they had a rough time in school being called “Jap.” “You gotta go back,” and stuff like that.

We were only there for six months in Litchfield Park. My mother didn’t like it there so she wrote to her mother and said we’d like to have some money to go to Hawaii. Because my grandparents were in Hawaii at the time. She was left in Japan in year 1900. She was born in 1899, so she was only a year old when they left her and they figured they were going to go to Hawaii to make their golden dream, whatever you want to call it, to make lot of money. But they never did go back to Japan.

Who raised her then?

Her aunts and her grandmother raised her.

So she felt like she wanted to go back in order to be with her parents?

Well, it was rough living in Litchfield Park. And they promised to build a home for us. They built the foundation and put the concrete down, put the foundation down, and that was it. So we lived in a tent for six or seven months. The army ten man tent. It was tough. So we’d take our baths outside in the open, because we had no running water in the trailer in we were staying in. And no running water through the tents.

Why wasn’t it finished?

I don’t know. All my father told us was that they’re going to build a house and it’s going to be done. My father and my brother George, they stayed there for another four, six months maybe. But they never did finish the house, never even started the house.

So we went to Hawaii and stayed with my grandparents for two and a half years. So that’s the bottom five [siblings]. There’s a top five who were already in Chicago and back in the Midwest. My youngest sibling was born in camp in 1944, Gary. So that’s how we became five and five.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on September 28, 2016.

© 2016 Emiko Tsuchida