The month of September is important for the people of Mexico because it celebrates the anniversary of its Independence. In the year 1910, the celebrations were grand and special as the first centenary of the Independence of Mexico was celebrated with multiple activities.

The government of General Porfirio Díaz prepared the celebration with great care and in advance and invested a large amount of effort and money in works to commemorate such an important anniversary. The most representative monument that was erected was undoubtedly the Independence Column, which was located right on one of the most important avenues in Mexico City: El Paseo de la Reforma.

The main buildings such as the National Palace and the Cathedral were illuminated for the first time with hundreds of electric lights as a symbol of the modernity that the country had entered according to the desires of President Díaz himself.

But not only the people of Mexico celebrated such an important anniversary. The Mexican government invited diplomats from other countries to take part in the celebrations. The representatives of seven countries sent a special representation, a participation that showed the interest they had in their relations with Mexico. The government of Emperor Meiji sent one such delegation which was led by Baron Yasuya Uchida and his wife. Together with Uchida, a military delegation was appointed, chaired by Lieutenant Colonel of the Imperial General Staff, Konishige Tanaka, and Captain Totukataro Tanaka, with the purpose of highlighting the Japanese delegation. In addition to them, the diplomat Kinta Arai was asked to support the delegation of his country, who spoke perfect Spanish. Arai, decades later, would be one of the first foreign professors at the National University, in charge of teaching classes on Japanese culture and language. 1

For the special diplomatic envoys who arrived in Mexico, the government of General Díaz decided to house them in the most imposing mansions in Mexico City, which is why they asked their owners to serve as hosts for such important guests. The Japanese representation was housed in the “castle” of Mrs. Lorenza Braniff, a mansion located on the same Paseo de la Reforma.

As part of its participation in the centenary, Japan sent a magnificent exhibition of Japanese products that was mounted at the National Museum of Natural History, better known at that time as the Crystal Palace (current Poplar Museum). On September 2, the president of the republic himself and his entire cabinet, along with the Japanese ambassador to Mexico, Kuma Horigouchi, were in charge of inaugurating the exhibition.

The exhibition of Japanese objects was a success, as the products such as furniture, fabrics, tableware and vases that were exhibited were highly appreciated and put on sale. The wealthy sectors of Porfirian society began to take an interest in the importation of the goods that Japanese industry manufactured.

The most important newspaper at the time, El Imparcial , reported extensively on the exhibition and the Japanese presence. He highlighted in his articles that Emperor Meiji gave Mexico two beautiful porcelain vases, inlaid with pearl and gold that were designed especially for Mexico with designs of eagles, the national patriotic symbol.

President Díaz, upon receiving the message and the present that Japan had sent, thanked them with the following words:

“It is also very much appreciated that the delicacy of His Majesty the Emperor has gone to the extreme of not only sending a Special Mission composed of such worthy and honorable personalities, but also of making evident his benevolent esteem towards Mexico with the precious gift that you have received. pleasure in giving us, a gift that Mexico gladly accepts with its two meanings: the transcendental of the good relations that unite us and the mastery of the Japanese, who also know how to distinguish themselves when it comes to not allowing themselves to be taken away from the adjective that they have legitimately earned from unsurpassed artists.”

The exhibition in the “Japanese Pavilion,” as the Crystal Palace was popularly called, was open daily until October 30 of that year with hours from nine in the morning to six in the afternoon. The exhibition was such a success that on Saturdays, Sundays and holidays it remained open until eight at night. Admission was 30 cents per person on weekdays and 50 cents on Sundays and holidays. Children under seven years old were admitted free of charge.

The friendship and interest between the Japanese and Mexican governments had been strengthened not only by diplomatic ties, but rather by the emigration of large numbers of Japanese who began to arrive en masse in Mexico starting in 1897. By the year 1910 there were About 9 thousand emigrants arrived. Japanese workers were looking for a better future in Mexico, they worked as farmers in Chiapas or as workers in the sugar mills of Oaxaca and in the mines of Coahuila and Chihuahua. Communication between both countries was carried out by modern steamships that connected the ports of Yokohama with Manzanillo and Salina Cruz. A Japanese steamship company made regular trips between both countries, a situation that allowed trade and emigration to flow constantly.

The presence of the Japanese community was noted in the same exhibition. On the land adjacent to the Crystal Palace, a Japanese garden was built that was created by Tatsugoro Matsumoto, an emigrant who had lived in Mexico for more than a decade. Matsumoto was in charge of the care of the gardens of the Catillo de Chapultepec and the interior arrangements, the place of residence of President Díaz. The community as a whole also participated in the various centennial celebrations, as the press reports, the migrant workers had earned recognition in the various places where they resided for their discipline and responsibility at work.

However; Despite the integration of the Japanese community in Mexico, the emigrants were not seen well by the North American government. Japan's imperial expansion in Asia and its consolidation as a great power meant that the differences between the United States and Japan had repercussions on the lives of the tens of thousands of emigrants who lived in various countries in America. The North American government maintained that migrant workers were the “invasion army” of the Japanese Empire and that behind the poor Japanese miners working in Mexico “spies were hiding.” Likewise, the United States distrusted President Díaz because, according to its interests, it considered that the ties between Mexico and Japan were too cordial.

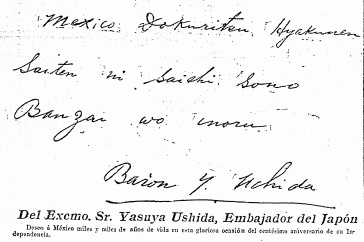

The excellent relations and the centenary celebrations were therefore not immune to the disputes between the United States and Japan, differences that would take on an unusual intensity and that would unleash the Pacific War in 1941. In this environment, Uchida expressed, in a note he left to the newspaper El Imparcial , his best wishes for the people of Mexico with the following words: “I wish Mexico thousands and thousands of years of life on this glorious occasion of the hundredth anniversary of Independence.”

Note:

1. Arai married a Mexican woman. His three children were outstanding Mexican professionals in each of their fields. See Shozo Ogino's article at http://www.mx.emb-japan.go.jp/sp/anecdota_marzo_05_2016.html .

© 2016 Sergio Hernandez Galindo