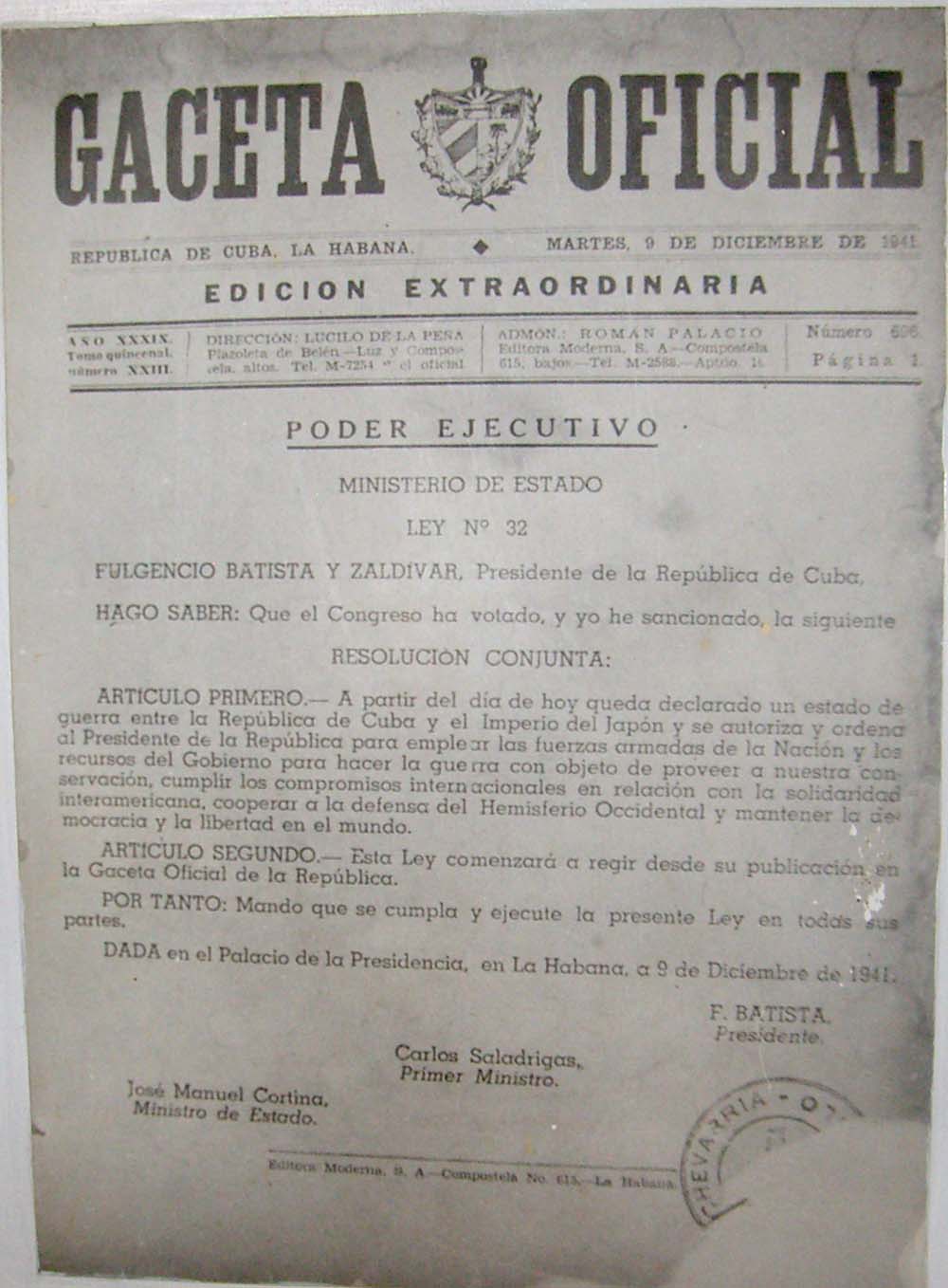

One lesser known fact about Cuban history is that the United States and Cuba were allies during World War II. The Cuban government declared Japan an enemy of the state on December 9, 1941, just a few days after the attack on Pearl Harbor in the United States. On this day, Cuban Law Number 32 was signed into law by Cuban President Fulgencio Batista which declared:

“A state of war between the Republic of Cuba and the Japanese Empire and authorizes and orders the President of the Republic to employ the armed forces of the Nation and the resources of the government to fight the war with the goal of providing for our conservation, fulfilling our international agreements in relation to Inter-American solidarity, to cooperate in the defense of the Western Hemisphere and maintain democracy and the liberty of the world.”1

In August of 1942, German submarines sank two Cuban frigates. This action prompted President Batista to allow the establishment of U.S. military bases in Pinar del Rio for the purpose of training U.S. and British air force personnel.2 This significant move established Cuba’s verbal commitment to assist the United States in the defeat of the Axis powers, including Japan.

Another lesser known fact is that the Batista regime, following the same policies of the Roosevelt administration, interned 350 Japanese Cubans in a prison called the Presidio Modelo from 1943–1946. Almost all of them were innocent Cuban citizens.3 The Isle of Pines (la Isla de Pinos), today called the Isle of Youth (la Isla de Juventud), is where 341 Issei and 9 Nisei Japanese Cuban men were detained without cause.4 Added to the Japanese detainees were 114 Germans, 49 Italians, two Chinese, and one Spaniard. (See Appendix A [original list] & Appendix B [English translation]) The United States exerted pressure on Cuba and other Latin American countries to detain Japanese, Germans, and Italians.

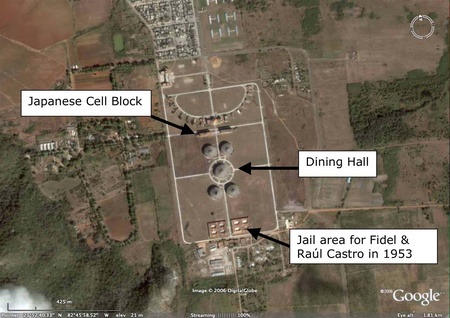

Pine trees cover a large part of this tiny island which is approximately 2,200 km2 and 60 miles south of Surgidero de Batabanó, a port town approximately 30 kilometers south of Havana.5 The Presidio Modelo consisted of four circular jail units, one circular dining unit, and two six-story rectangular buildings on a large plot of land peppered with armed guard towers throughout the perimeter.

In 1953, the Presidio Modelo housed the Castro brothers (Raul and Fidel), along with their captured comrades. Fidel and Raul were not put with the rest of the common criminals, but in a separate building approximately 300 feet behind the circular units. Here, Fidel received the education “in radical politics that had been lacking in his early schooling.”6 Today, the Presidio Modelo is a museum highlighting its significance in Cuban history.

With regard to the Japanese interned in the United States, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was signed by President Ronald Reagan, authorizing a payment of $20,000 to “each internee, evacuee, and persons of Japanese ancestry who lost liberty or property because of discriminatory action by the Federal Government during World War II.”7 Many Japanese Americans had been lobbying the United States government for an official apology for its actions during World War II. However, with regards to Japanese interned in Latin American states such as Cuba, it is interesting to note that within one year “the Department of Justice adopted rules to deny compensation to the internees from Latin America on the grounds that they were ‘illegal aliens’.”8 Eventually, a coalition called the “Campaign for Justice,” consisting of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, the Japanese-Peruvian Oral History Project, and the National Coalition for Redress Reparations was formed in 1996 with the goal of having the U.S. government apologize and offer compensation for Japanese internees from Latin America.

In 1998, President Bill Clinton formed an agreement called the “Mochizuki settlement” which provided the apology and a sum of $5,000 to each Japanese Latin American.9 Many Japanese Latin Americans did not apply for the funds, due to the short application period provided by the U.S. Congress, as well as communication issues. What is not known is if any Japanese Cubans were successful in applying for and receiving funds. The provisions of the Cuban embargo would most likely have made the transfer of funds to Cuba very difficult.

When Fidel Castro’s Revolución occurred in 1959, Japan’s relations with Cuba soured as the United States, now allied with Japan, imposed what started off as an arms embargo on Cuba. The U.S. embargo would affect not only Japan–Cuba relations but others as well, notably Soviet–Cuba relations.

Notes:

1. Cuban Government. Executive Authority, State Ministry. Gaceta Nacional. “Ley No. 32 de 9 de Diciembre de 1941.” Dec 9, 1941. Translation by author.

2. Gott, Richard. Cuba: A New History. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2004. p. 333n5.

3. The Japanese were kept separate from the other inmates, although the open yard allowed intermingling during the daytime. In the circular units, there was an open area in the middle with the cells lining the outside rim on eight levels. There were no cell doors so prisoners were free to intermingle with each other. However, there was a lot of infighting and prisoners would fabricate weapons using whatever they could get a hold of. Since there were no cell doors, it provided a prime opportunity for inmates to murder one another during the night. The cells in the circular units were simple, two bunks and a toilet with a fairly large space of approximately three by five feet for a window which had no bars. Prisoners on the lower levels could have jumped out of their cells, but again, there were guards everywhere so even if they managed to escape the Presidio Modelo they were still stuck on the Isle of Pines, approximately 28 miles long from north to south and 30 miles long going east to west.

4. Issei are first generation Japanese, born in Japan. Nisei are any second generation Japanese born abroad. Sansei is third generation born abroad. Yonsei is fourth generation.

5. Cuban Government. “Cubatravel.cu: The Cuban Portal of Information: Information- Cuban Archipelago.” Accessed November 6, 2006.

6. Gott, Richard. Cuba: A New History. p. 151.

7. United States Government. Department of Justice. “Japanese American Internment.” November 15, 2006.

8. Masterson, Daniel M. and Sayaka Funada-Classen. The Japanese in Latin America. p. 280.

9. Ibid. P. 280.

<<Appendix>>

A—List of Japanese Prisoners (Original)

B—List of Japanese Prisoners (Translation into English)

*This article is an excerpt from the master’s research project, “Japanese Cubans: Past, Present, and Future,” by Christopher David Cheng (Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, December 19, 2006).

© 2006 Christopher David Cheng