Tadatoshi and Setsuko, my parents, arrived in the capital of São Paulo, coming from Vera Cruz, in the interior of São Paulo, in 1955, with 5 children.

After a brief stay in a house on the east side, in the district of Ermelino Matarazzo, my father acquired a small grocery store/ mise , nearby.

As the customers didn't learn to pronounce their names, Tadatoshi became Mário and Setsuko, Helena. Seu Mário and Dona Helena had to communicate in Portuguese with customers, with all the unimaginable difficulties. Thus, our Nihongo was restricted to some expressions and words such as hai, iie, benjo, baka, itai and furo ; greetings such as Ohayo , Konnitiwa , Konbanwa and Sayonara ; foods: daikon and tsukemono , oh, and sake because we also sold cachaça and tabako . And other words that I always forget to remember.

The Nihongo schools were far from our little village and so my brothers and I, without studying it, were embarrassed by the visit of a Japanese relative or friend of the family.

I remember that, around noon, we called dad for lunch.

-Gohan !

And I heard from a funny customer: - Are you going to catch a frog, Seu Mário?!

The family subscribed to two newspapers: Jornal Paulista , which was later acquired by Jornal Nippak , from the Japanese community, and Diário Popular , which no longer exists. When the newspaper fell, the joke was inevitable:

- the newspaper... shimbum ! in floor.

Shimbum ! it was an onomatopoeia of the sound of the newspaper falling to the floor.

My best friends were the Ietsugu brothers: Hiroshi, Sigueru and Massatoshi. At their house, they spoke to Okaasan in Nihongo. I listened, imagined the content of the conversation, but rarely asked the meaning of a word. Shy, at most he would risk a mizu doozo . Thanks to the Ietsugu, I participated in an undoukai , but at the end of the race, when I was leading, I fell. Without the undou , my world fell apart and I lost the test.

My Nisei classmates in junior high school, currently elementary school I, studied Nihongo but had difficulties with Portuguese. I remember a Portuguese competition where anyone who got the question wrong on a rolled-up piece of paper was eliminated. Of the 9 or 10 Nisei, only I continued in the competition with my friend Amaury. The following week, with the school principal present, I won the final duel. This academic achievement led me to Literature and Human Sciences while Hanada & co. automatically took the path of Exact Sciences and Economics. Unconsciously, the erroneous idea that Nihongo would not be missed by me was consolidated.

In high school, now the Fundamental II course, Portuguese teacher Avelina praised my essays. At that time, I wrote poems and even published them on the poetry page of the magazine A Recreativa and on the Portuguese cover of Jornal Paulista , in the early 1970s. Nihongo became increasingly distant.

At the International Song Festival, on TV Globo, Kyu Sakamoto was successful with the song Sayonara, Sayonara, years before, Sukiyaki , by Rokusuke Ei, became a hit in Brazil. I memorized the lyrics and sang in Japanese, without understanding the meaning of the songs. This had already happened when Italian music prevailed and I sang in Italian without understanding any nonsense, just as I sang Beatles songs with my poor English . At least Nihongo survived in my memory.

In the 80s, I took a brief Japanese Conversation course but due to mistakes such as calling my doctor colleague oishii instead of ishi , I was embarrassed and dropped out of the course.

In addition to English, I learned a little Français and Español. I've always liked playing with words from other languages. For example, I know of phrases in Portuguese that seem to be from another language. For example, “Eating an apple makes you sweat.”, doesn’t it sound like a phrase in French? And “Does ó have a u sound?” doesn’t remind you of English? And “If it snowed here, would you wear skis?” Doesn't it sound like someone speaks Russian? And “Canker sores burn and hemorrhoids the same”, doesn’t it sound like German? The phrases that sound like Japanese are in the statement I gave to the Japan-SP Foundation about the Marugoto Course, in 2013.

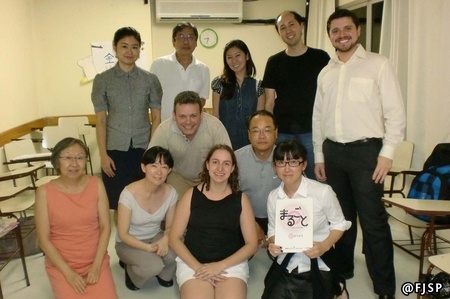

“When I turned 60, I gave up and said: Sayonara, Nihongo! Until I found out about the Marugoto Course. Little by little I went fromあいうえお/aiueo toやゆよ/yayuyo . The mystery is over. I only knew how to say, in Japanese, “Bamboo fishing rod” and “Chiclé chewing gum”, now I know how to say Doozo yoroshiku and Tanjoobi Omedetoo. And I say Sumimasen when I want to disappear from class early. The course is “3 D”: Democratic, dynamic and fun. Another D: It’s Awesome! That's why, when leaving Marugoto, I don't just say Sayonara! but also Arigatoo !”

I was excited about the course until the kanji appeared. I found them extremely muzukashii and dropped out of the course again.

In 2014, much to my surprise, my text on Nikkei Names was published on the website discovernikkei.org . in different languages. Even so, I didn't feel like going back to the nihongo course.

In order not to forget nihongo , I made mnemonic texts:

My family

Hello, I'm Watashi Kazoku and I want to introduce you to my family. My father is Chichi , he doesn't spread it, and my mother is Haha , funny, right?; my older brother is Ani and my older sister is Ane ; my younger brother is Otooto and my little sister is Imooto . My grandfather is Sofu ; my grandmother is Sobo . My wife is Tsuma Kanai. My children are Oniisan , the eldest; Oneesan , the oldest, Otootosan , the youngest, and Imootosan , the youngest. My dog is called Inu and the cat is Neko .

My friends

I'm happy because I have friends of all kinds. Look:

The best: Oto Modachi

The one on the side: Naomi Yoko

The one from the subway: Chica Tetsu

The banker: Eliza Ginkooin

The little one: Chisato Chiisai

The interesting thing: Luciano Omoshiroi

The dentist: Leonardo Haisha

The artist: Tereza Origami

The funny one: Eriko Tanoshii

Sensei: Maki Kyooshi

The engineer: Paulo Enginia

The important thing: Sussa Taisetsu

The decorator: Matheus Ike Bana

The Drinker: Sake Nomimasu

The stylist: Diego Fasshon

The sushi chef : Hiroyuki Tempura

The poet: Genésio Haiku

The journalist: Aldo Shimbum

The journalist 2: Alex Nippaku

The photographer: Luci Shashin

The handyman: Lion Shimasu

The polite one: Renato Oneigashimasu

The sad one: Carlos Kanashii

The cheerful one: Andoré Ureshii

The slacker: Hiromi Hima

The vegetarian: Celia Yasai

The birthday boy: Kyoo Tanjobi

The Busy: Toire Isogashii

The doctor: Vanessa Isha

The deaf man: Moo Ichido

The glutton: Hayashi Hashi

The actor: Ricarudo Kabuki

The lawyer: Lauro Bengoshi

The chicken-eater: Tonico Toriniku

The one of summer: Natsume Natsu

The One of Autumn: Akira Aki

The spring: Haruko Haru

The fraternal: Ietsugu Maitoshi

The consumerist: Kyoko Kyaku

The smoker: Coutinho Suimasu

The fishmonger: Claudio Sakana

The footballer: Ivan Sakkaa

The fisherman: Denis Tsuri

The scholar: Claudine Benkyoo

Pop and chic: Bruno Manga

The animated one: Alessandra Anime

The Korean: Arumando Kankoku

The “Chinese”: Letícia Chuugoku

The passenger: Basu Subo Desu

The singer: Karake Utaimasu

The grandmother: Sumako Morita Sobo

The surfer: Taka Surufa Honda

The pretty one: Lyvia Matsubarashii

Now, at 64, am I a goner? Will I be a bakka forever? lol How I'm cherishing the dream of visiting Japan, Nihon go ! In the near future, I must return to nihongakkoo to perfect my Nihongo . I don't want to be the odd one out. I don't want to be a stranger to Nihon .

© 2016 Jorge Nagao