Imagine having your marriage examined on the front page of metropolitan newspapers across the country and around the world. This was the case for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission’s first minister and his bride in the winter of 1910, the Reverend Joseph Kenichi Inazawa and Miss Kate Alice Goodman.

What caused all the commotion? Neither of them was a wealthy land baron, railroad tycoon, or royalty. Nor were they notorious for questionable politics or crimes. Both were in their forties and had known each other for some time. Theirs was a marriage between a respected Presbyterian clergyman and a long-time church worker that should have received a quiet announcement in the society section of the daily news.

He was Japanese. She was Caucasian. And, their groundbreaking marriage triggered intense public fascination of the kind we see in today’s celebrity media. It was a public spotlight that would make anyone want to run for the hills…or maybe for the peatlands of Wintersburg.

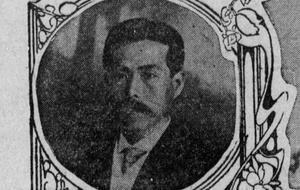

Reverend Inazawa

Born in the Iwami Province in Japan in 1863, Rev. Inazawa arrived in the United States in the late 1800s after attending seminary in Tokyo. He performed his post-graduate work at the San Francisco Theological Seminary, graduating with the class of 1894. The San Francisco Call reported he was one of two Japanese ordained at the annual Presbytery convocation in April 1896.

Prior to his work in Los Angeles, Inazawa worked as itinerant Presbyterian clergy throughout California, including in San Francisco, Salinas, Watsonville, and Santa Cruz. The Japanese Presbyterian Church of Salinas, California (Lincoln Avenue) credits Inazawa with the establishment of the original mission in 1898, meeting above a blacksmith’s shop. By 1902, he had negotiated a land purchase for the mission. The present-day church’s website describes Inazawa as “a rare person of integrity.”

Rev. Inazawa’s biography for the San Francisco Theological Seminary alumni indicates he helped compile the selected poems, artwork, and addresses for Spirit of Japan, dedicated to Dr. Ernest Adolphus Sturge, M.D., Ph.D.—a leader of the Japanese mission work on the West Coast for the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A.—and translated a number of Presbyterian publications.

By 1902—the same year Presbyterian clergy began meeting Japanese farmers in Wintersburg—the Japanese Presbyterian Church of Los Angeles was forming. Church records indicate Rev. Inazawa arrived in 1905, developing the Los Angeles group into a “regular Presbyterian congregation.” The Los Angeles Herald wrote Reverend Inazawa was fluent in English and the scriptures, and that he had been “actively identified with Presbyterian missions and churches” in the United States for twenty years.

Miss Kate Alice Goodman

Kate Goodman was originally from New York, a University of Chicago graduate, and was described by the New York Tribune as coming from a “good New York family.” She is reported as working for nine years to help establish Japanese missions in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Prior to the marriage, she had been teaching at a Japanese school in Moneta (Gardena, California).

She and Reverend Inazawa met while “thrown together” teaching bible classes and they formed an “attachment.”

Reports of the engagement between Reverend Inazawa and Kate Goodman in the spring of 1909 made news across the country and in other countries, including New Zealand’s Evening Post. The Olean Times (New York) reported that “Mr. Inazawa was greatly surprised when he learned his secret had leaked out but freely acknowledged the truth of the report.” Like anyone today wisely trying to avoid the paparazzi, Reverend Inazawa told the newspaper that no date had been set for the wedding ceremony.

The Los Angeles Herald reported in 1910 that “Cupid was sent scampering away until she could read and investigate the advisability and probably consequences of such a union.” At 42 years old, Kate Goodman was not prone to the flowery language that the Herald used when writing about the two.

Knowing there was more than a little interest about their marriage, Kate Goodman prepared a written statement that was delivered to the Los Angeles Herald on February 23, as she and Reverend Inazawa left for Laguna, New Mexico to be married.* The Herald reported her as telling friends, “Say for me that I am happy. I don’t care what the world thinks. Joseph and I are happy.”

Goodman’s written statement can easily be interpreted into 21st Century language as, “We’ve got this. Everything is fine.” There is a veiled admonishment to the media about sensationalizing the marriage.

Goodman writes, “When the marriage of two persons of humble circumstances is given space on the first page of a metropolitan daily the only inference to be drawn is that such marriage is regarded as sensational in character. When the hitherto law abiding members of a community leave the state in order to consummate a legal marriage, a decent regard for the opinions of mankind would seem to warrant a word of explanation…”

“It has been suggested to me that this marriage may be regarded by some as a piece of emotionalism unsupported by the judgement,” continued Goodman. “Such is very far from the truth. In fact neither of us has any startling record of rash acts committed in the past and after 40 years of age character should be somewhat settled, it would seem…In the choice of a husband I certainly have not been unduly precipitous…I have given to the subject the most continuous concentrated serious and honest thought of my life.”

Goodman concludes her statement with a Tennyson quote, Genevieve to King Arthur, “we needs must love the highest when we see it.” As with the leaked engagement news, Goodman’s statement was included in newspapers around the country—often on the front page.

A 1910 edition of the Pacific Presbyterian announced the marriage, “Rev. J.K. Inazawa and Miss Kate A. Goodman were united in marriage last week in a very quiet way. The engagement was announced some time ago.” The announcement concludes, “This new relation ought to increase the efficiency of both, as the promise is that one shall chase a thousand and two put ten thousand to flight.”

In Wintersburg

At the time of the marriage, President Taft had been in office a year and Washington was embroiled in the Congressional investigation of the Pinchot–Ballinger controversy. News about the Inazawas joined articles about Theodore Roosevelt’s hunting exploits in Africa and the Empress Eugenie’s last days on the French Riviera. New Mexico and Arizona had yet to be officially admitted into the Union. Railroad tycoon James J. Hill was chastising Americans for living beyond their means, while John D. Rockefeller announced he would donate a billion dollars to charity over his lifetime.

The Inazawa marriage—along with the features on Roosevelt or Empress Eugenie—does not seem to have had the same buzz in Wintersburg Village as in metropolitan society. Perhaps the diverse population was focused on the hard work of farming and creating a community.

In his 1982 oral history interview for the Honorable Stephen K. Tamura Orange County Japanese American Oral History Project, California State University Fullerton Oral History Program Japanese American Project, Henry Kiyomi Akiyama mentions Reverend Inazawa. His is the only oral history found that mentions the couple. Akiyama said Reverend Inazawa “was the first reverend after the missionary building was built here and he was married to a hakujin (Caucasian).” And, that’s it. Seventy-two years later, it was a simple observation.

A permanency of happiness

The Inazawas had many supporters. In the national newspaper, The Christian Work and the Evangelist (Vol. 88, page 348) in 1910, included a news item about the Inazawas shortly after their marriage, “Analyzing a future husband.”

“In Laguna, New Mexico, has occurred a marriage of the Rev. Joseph Kenichi Inazawa and Miss Kate Goodman. He is pastor of a Japanese Presbyterian Church and she is a mission worker. He is 46 and she is slightly his junior,” reports the newspaper, explaining that Goodman had to defend the choice of her husband.

“Anyone who considers her husband is all right biologically, anthropologically, sociologically, psychologically, and theologically ought to be happy!” The newspaper continues, “many of our girls only stop to inquire if a fellow is financially right. It is better to trust to induction and deduction every time!”

A few years later, Neeta Marquis wrote about the Inazawa marriage in a 1913 article for The Independent, “Interracial Amity in Los Angeles, Personal Observations on the Life of the Japanese in Los Angeles.” California writer Marquis authored books about Presbyterian history, art, and works such as Earth’s Story of Evolution: From Cosmic Dust to the Present Age.

“Between two and three years ago, when the native pastor of the Japanese Presbyterian Church, Joseph K. Inazawa, a scholarly and interesting man of highly pleasing personality, was married to an American lady, a reception was tendered the couple at the home of one of the prominent American ministers, and the American and Japanese friends of the two mingled as guests,” writes Marquis. “The alliance caused considerable comment at the time, the general sentiment of the American public not personally acquainted with the principals being, of course, opposed to the union.”

“Mrs. Inazawa, then Miss Kate Goodman, a Christian woman of independent character, experienced in teaching and normal school work, formerly a student at the University of Chicago, had for nine years worked among and studied the Japanese in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles,” Marquis explained. “As a concession to public opinion, she published a statement defining her attitude on the matter of her marriage. The statement…was a clear, finished, logical and sane production…”

Marquis writes about meeting with Mrs. Inazawa and finding her to be “a thoroly (sic) normal American woman of the broadly intellectual type, possest of a delightful sense of humor and more than willing to answer the questions I was eager to ask her.” Kate Inazawa is reported as telling Marquis that “she would be glad for the American public to know that over two years of life as the wife of a Japanese Christian gentleman had in no particular altered the personal attitude toward inter-racial marriage which she stated at the time of her union with Mr. Inazawa*.”

Marquis summarizes that the Inazawa marriage is successful because the “husband and wife are one in ideals, aims and spiritual outlook” and that “a permanency of happiness can be expected.”

The Wintersburg Mission

Reverend Inazawa held the first official service in the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission building in 1910, during his first year of marriage to Kate Goodman. The couple would have been the first to live in the manse adjacent to the mission, as both buildings were completed in 1910 per a church history compiled in 1930 by Reverend Kenji Kikuchi.

*Author’s note: New Mexico—where the Inazawas traveled in order to marry—repealed anti-miscegenation laws in 1866. California banned interracial marriage between 1850 to 1948. In 1922, the U.S. Congress passed the Cable Act, which retroactively stripped the citizenship of any U.S. citizen who married “an alien ineligible for citizenship.” In 1948, the California Supreme Court in Perez v. Sharp ruled that the anti-miscegenation statute violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, repealing anti-miscegenation law and becoming the first state to do so since Ohio in 1887. In 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that the state bans still in place violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on July 29, 2012.

© 2016 Mary Adams Urashima