Just two months away from the Rio Olympic Games, let us take a moment here. Do you know that once in the history of the Olympic Games, one podium was dominated by three athletes, all from different countries but of the same Japanese ethnicity? In the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games, the podium for the 1,500-meter freestyle in swimming was taken by Ford Konno, a Japanese American from Hawaii who took first place, Shiro Hashizume from Japan who took second place, and Tetsuo Okamoto, a Japanese Brazilian who took third place. In Brazil, not only was Okamoto a hero who brought the first medal ever in swimming but he was also the first one to achieve such success in the Nikkei community—a legendary story to be remembered in every Olympic Games by Nikkei people all around the world.

Tetsuo Okamoto (who passed away in October, 2007) was a Nisei Brazilian born in Marilia in 1932. His father Sentaro was from Hokkaido, and his mother Tsuyoka was from Fukuoka. Located approximately 440 kilometers away northeast of São Paulo, Marilia is a flourishing city along the Paulista Extension Railway. Thousands of Japanese immigrant families worked in farms before and after the war, and the Japanese were especially spotted frequently even in the inland of the state of São Paulo.

Tetsuo’s birth registration number was 36, which is the history of the city itself. He started swimming when he was about 7 years old, in the 1940s just before WWII.

According to the Paulista newspaper on September 18, 1952, Shinzo Tozaki and Yoichi Yamazaki built a “Japanese pool” on their own farmland at their own expense on October 8, 1940. The pool was 25 meters long and 12 meters wide. The estimated cost of 30 contos ended up at 50 contos. Back in those days, it was extremely rare for Japanese people to own a pool.

Suggested by his parents, Tetsuo who had childhood asthma, started swimming there to strengthen his body. In the Nikkey Shimbun on August 14, 2004, Okamoto is quoted: “In the countryside we didn’t have such things as a tiled pool, and ours was built as they held back the stream water, so I often saw frogs swimming. The water got cloudy once we started swimming, and I couldn’t see anything in the water with my eyes open.” This was his first experience.

A light of hope in the difficult time for Japanese immigrants

The periods before and after the war, when Okamoto spent his time as a pre-teen, were times full of hardship for Japanese immigrants in Brazil.

Under the regime of Getulio Vargas which began to gain power in 1937, its nationalism policy placed a ban on foreign language education for children under the age of 10 in 1938, and all foreign language schools (Japanese, German, and Italian) were forced to close by the end of that year. In July, 1941, all Japanese papers ceased publication. The Japanese immigrants were deprived of their hope for the future (Japanese education for their children) as well as their eyes and ears (ways to get Japanese information) at the same time.

At the Rio De Janeiro Meeting of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the American Republics which was led by the U.S. and held in January, 1942, ten countries in South America except for Argentina agreed on breaking off economic relations with the Axis powers, and on the 29th of that month, the Brazilian government declared the severance of diplomatic relations with the Axis powers.

The Security Administration of the state of São Paulo, as a way to enforce such policy on “enemy citizens,” placed severe restrictions on Japanese immigrants such as banning distribution of things written in their first language, use of such language in public, traveling without permission from the Administration, and moving without prior notice to the Administration.

The “Japanese pool” was completed, yet there was some problem in the paperwork which resulted in the closure soon after its opening. Soon they headed to São Paulo and talked with the head of the Physical Education Bureau.

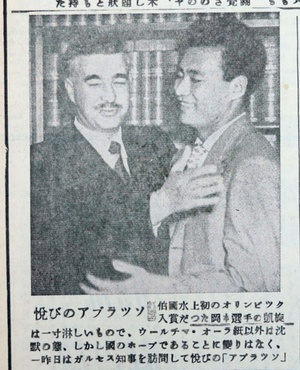

They were pleasantly surprised. “They kindly told us what to do, and even though we were told to close the pool temporarily during the wartime, Mr. Pasilia gave us his permission and so we ‘passed.’ We can say that Chief Pasilia made Tetsuo Okamoto a world-class athlete.” (quote from the paper) Being an exception to “enemy citizens,” Okamoto was able to continue swimming.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, starting from March, 1946, the “Winning or Losing Feud” broke out, forcing the Nikkei community to face unprecedented turmoil.

For the Japanese immigrants, their only source of Japanese information had been the Imperial Headquarters announcement from Tokyo Radio on shortwave since 1941 when Japanese papers were forced to cease publication. Brazilian papers reported American stratagems—they were brainwashed into thinking that way.

As a result, the community faced a crisis in which the Japanese were split into two groups, the winning group that refused to believe Japan’s unconditional surrender and the losing group that accepted the defeat. The feud ended up with more than 20 people getting killed among the Japanese themselves. Starting from April, 1946, the chaos peaked in July of the same year and continued until the beginning of 1947.

The publication of Japanese papers resumed at the end of 1946, and things gradually settled down. Yet the disunion lingered for nearly a decade after that.

In 1948, with the strong influence of the feud still in the air, Tetsuo who was only 16 years old at the time, competed in the South America games held in Uruguay.

“A night in the capital spent with thoughts on the first swimming battle” (Yukimura)—Tetsuo’s father Sentaro made a poem in delight.

Flying Fish of Fujiyama changed Okamoto’s life

In March, 1950, Okamoto experienced a life-changing event. On March 4th, the swimming team that led to building the Japan-Brazil relationship after the war arrived in Brazil. The team included Coach Masanori Yusa, Captain Shuichi Murayama, Hironoshin Furuhashi also known as “Flying Fish of Fujiyama,” Shiro Hashizume, Yoshihiro Hamaguchi, and others. Okamoto wouldn’t have imagined even in his dreams that he would be competing against Hashizume in the Olympic Games.

Already a representative of Brazil, for two months, Okamoto participated in friendly games that were held in cities with high populations of Nikkei such as São Paulo, Marilia, and Londrina in the state of Parana, together with the Japanese team. Okamoto was greatly inspired by the world’s fastest swimmers.

As a defeated nation, Japan could not participate in the 1948 London Olympic Games. However, as soon as Japan was allowed back into the International Swimming Federation in June, 1949, six athletes including Furuhashi and Shiro Hashizume were invited to take part in the U.S. Championships held in August in Los Angeles and set world records in 400-meter freestyle, 800-meter freestyle, and 1500-meter freestyle.

Since it was before the Treaty of Peace with Japan was signed, there were no U.S. dollars in Japan. The incredible world records were made possible with donations from officials of Japan Swimming Federation and the Nikkei in America. Local newspapers praised the team as “Flying Fish of Fujiyama” which heartened Japanese citizens so much.

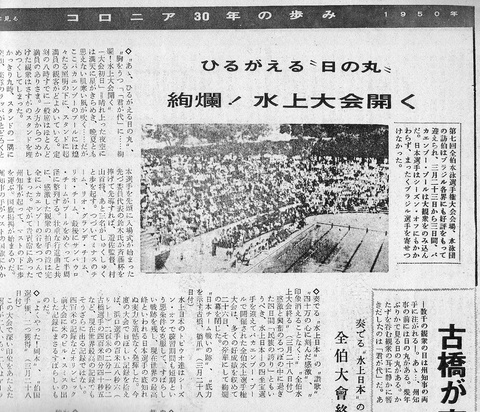

In the following year, on their way home after the U.S. games, the team was invited to South America by the Ministry of Sports in Brazil. The “Flying Fish” were at their peak. Using their visit as an opportunity, the Brazil Swimming Championships were held at the Pacaembu Pool in the city of São Paulo, and Furuhashi set the new South American record in the 400-meter freestyle, another great accomplishment.

At the time, Japanese immigrants who had been oppressed in the country received an unforgettable gift with the special care of the President. For the first time in eight years since the severance of diplomatic relations, a Japanese flag was shown in public. The sight of the flag consoled and empowered the hearts of Japanese immigrants who went through so many sufferings during the wartime.

The Japanese team gave Okamoto a piece of advice—if you want to succeed, you have to practice more. Until then he had practiced 1,000 meters per day, but he took the advice and began swimming 10,000 meters per day. (from the Nikkey Shimbun quoted above)

In the article in Folha De São Paulo on October 3, 2007, which reported the passing of Okamoto, it says that Okamoto “had to fight with cold since there was no heated pool at the time. He did the daily 10,000 meters of swimming with bloodshot eyes from chlorine. It almost seemed insane.” And it changed everything in his life.

It was the time when Brazil still had a great number of kachigumi (winning group) members who refused to accept the defeat of their home country, despite the visit of the swimming team from faraway Japan. In November, 1950, the Marilia police arrested 50 members of “Citizen Vanguard Unit,” a fraud group that took money from the kachigumi as returning home expenses. It was definitely a dark period of time in the city where the remains of the winning or losing feud were clearly visible.

Becoming a hero with fierce training

At the time in Brazil, people were still recovering from the shock of Brazil’s defeat in the final match against Uruguay in the World Cup that was held in their home country in 1950. The city of Marilia declared a city holiday and took Okamoto on a victory drive in a convertible, and the citizens welcomed him passionately. During the parade, however, Okamoto’s house was robbed with his valuables taken, a very Brazilian anecdote that accompanied the event.

The Nikkei community in Marilia wanted to give him a car as a celebration gift, but he declined the offer. “Olympic athletes need to be amateurs. If I get something that can be mistaken for a prize, I would lose my qualification as an amateur.” This was his thinking behind it.

Back then things were greatly different, unlike now where many professional athletes participate.

In the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games, on the podium of the 1500-meter freestyle were Japanese American Ford Konno from Hawaii in first place, Shiro Hashizume from Japan in second place, and Japanese Brazilian Tetsuo Okamoto in third place.

According to the Nikkey Shimbun quoted above, Okamoto was almost about to pass out at the final turn of the 1500-meter race. But he heard his father’s voice—“You are an offspring of samurai. Show your Japanese spirit before you die”—and he did. It’s a reflection of the time they lived. When told that he took third place, Okamoto was overjoyed and cried in delight.

It must have been such an emotional moment for him to stand on the podium after competing with Hashizume, one of the members of the Japanese team that excited Brazil in 1950, just two years before the Olympics.

Ford Konno was born in Hawaii in 1933 and was already a successful swimmer at McKinley High School in Honolulu and at Ohio State University. He won a total of three medals, two golds and one silver at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics and one silver at the following Melbourne Olympics (1956). He was a national hero in U.S. swimming.

However, “Flying Fish” Hironoshin Furuhashi ended up taking eighth place in the 400-meter freestyle in the Helsinki Olympics as he developed amoebic dysentery while he was in South America. He set a number of world records but did not win any Olympic medals in his lifetime.

When Okamoto passed away on October 2, 2007, Brazilian Association of Competitive Swimming (CBDA) grieved his death and declared “three days of mourning.”

© 2016 Masayuki Fukasawa