One hot summer afternoon back in 2008, my husband and I had just finished taking my mother to Huntington Library for her 83rd birthday. We decided to visit our old hometown Sierra Madre, where I spent most of my pre-teen years.

Even though we hadn’t planned on it, we thought by chance we might be able to meet up with Sho Nomura. Mom’s childhood friend Shag told Mom about Sho because she thought my husband John would want to talk to him. Sho was in China during World War II, and Shag knew that John was a champion of the People’s Republic of China.

So we headed up Grove Avenue, historically the street where many Sierra Madre Japanese lived and where the Issei had built a gakuen (language school). We see this old guy standing in his driveway looking out onto the street. Mom says, “I think that’s him.” So we back up and pull into his driveway. Mom gets out and goes up to the door to inquire if he is Sho Nomura.

YES, he is Sho Nomura! My mother makes the proper connections, mentioning Auntie Shag and that we were former residents of Sierra Madre. Mom motions John to the door—he jumps out of the car and asks Nomura-san if he would tell us about his time in China. Sho and his wife Florence graciously invite us into their living room and welcome John’s questions.

Sho eagerly brought out his photo album from a back room—it contained rich historical documents and photographs of this little-known chapter of U.S. history in China.

In 1944, a U.S. Army Observation Group, nicknamed the Dixie Mission, was sent to Yan’an, China. Sho Nomura was one of five Nisei to be part of the Dixie Mission. The mission was to get a better understanding of the political situation in China and try to facilitate a coalition between the Communists and Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang (KMT) forces to drive out the Japanese military invaders in China.

Yan’an was where the Chinese Communist Party forces had retreated to regroup and restrengthen their forces after near defeat by the KMT (which was more anxious to rout the communists than repel the Japanese). The Dixie Mission was an attempt to potentially ally with the Chinese Communist Party forces not only against the Japanese enemy, but to keep China from coming under Soviet influence post-war.

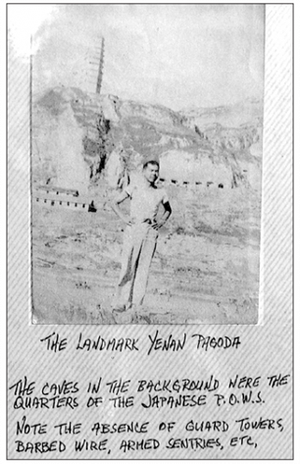

Sho Nomura and George Nakamura were the first Nisei to arrive in Yan’an, as guests of Chairman Mao and Generals Zhou En Lai and Zhu De, to interrogate Japanese prisoners-of-war. Koji Ariyoshi soon joined them, followed by Jack Togo Ishii and Toshi Uesato. There is a picture of Sho Nomura standing in front of the Japanese POW living quarters. His caption reads: “Note the absence of guard towers, barbed wire, armed sentries, etc.” as he remembers the Gila concentration camp where he enlisted with the MIS (Military Intelligence Service).

Sho said: “A lot of guys got upset being thrown in camp. I didn’t feel that way. Protests didn’t do anything. That’s why I volunteered for the Army. It was the only way to get out of there.”

Nomura’s memory book was filled with snapshots of the Americans, Chinese Communists, and Japanese prisoners-of-war who all lived in similar conditions in the Yan’an caves. Sho mentioned working with the famous Sanzo Nosaka, founder of the Japanese Communist Party, who was working with the Japanese POWs.

One of Sho’s proudest accomplishments while he was there was the invitation he created for the Christmas party the Dixie Mission hosted for the locals. He has signatures of Chairman Mao, General Zhou En-lai, and General Zhu De and many other high-ranking officers in the Chinese Communist Party and People’s Liberation Army.

Sho remembers that there was a dance every Friday night in the pear orchard, and Mao used to be a regular. When Sho had appendicitis he had the chance to fly out of Yan’an to get his appendix removed, but he decided to trust the local doctor. The Army photographer took shots of him during and after the operation.

Sho had a very positive experience when he was there. The Dixie Mission, under the command of Col. David D. Barrett, experienced first-hand the contrast between the Communists and the Nationalists. U.S. Embassy 2nd Secretary John S. Service criticized the KMT and Chiang Kai-shek as being “fascist,” “undemocratic,” and “feudal”; he described the Communists as “progressive” and “democratic.” These reports and shared assessments would take David Barrett and John Service down during the McCarthy Red Scare in the 1950s—both questioned by the HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee).

Sho said, “It was ridiculous. They were accused of being Communists. It was absolutely ridiculous. That McCarthy was off his rocker—he was nothing but a rabble-rouser…. It was not like I was supporting Chinese communism, none of that crap.”

Sho’s wife Florence was in Japan during and after the war. Shoso was in the civil service in U.S.-occupied Japan for five years as an interpreter. Sho and Florence had their first daughter, Ann, in Japan: “It cost me $5 to have my daughter in Japan—cheaper than meat.”

Before coming back to the States in 1951, Officer Cromley met with Nomura in Tokyo with advice—“Sho, don’t ever mention you were in Communist China” [because of the McCarthy Era]. So stories like Sho’s were easily silenced in this kind of climate.

Sho went back twice at the invitation of the Chinese government (1978 and 1991), along with other members of the Dixie Mission as some of the first goodwill ambassadors for the U.S. to the People’s Republic of China. And Nomura has been a goodwill ambassador for mainland China in the U.S.

John asked Sho what he thinks of China today: “I don’t think Communists are that strong any more. The Chinese are practical people, you know. They are more interested in business and commerce than politics.”

When asked why he had such a positive image of his time in Yan’an: “Its not a common-day experience. It’s all part of history.”

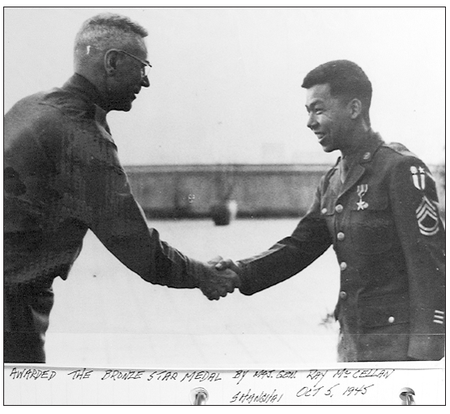

And what a history to tell—thank you, Mr. Nomura, for your extraordinary service to U.S.-China relations and representing the special role of Nisei MIS members in World War II. Nomura received his Bronze Star in Shanghai in 1945 and 65 years later, the Congressional Gold Medal along with the 442nd, 100th Battalion, and 6,000 Japanese Americans who served in the Military Intelligence Service. And in 2003, Sho and Florence were the proud grandparents of Nisei Week Queen Nicole Cherry.

Hats off to Sho Nomura, who is now 97 years old and has been “through the fire” and back!

Note: Col. Harry Fukuhara’s interview transcript with Sho Nomura is at the National Japanese American Historical Society (NJAHS) archive in San Francisco Nihonmachi. Fukuhara is in the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame (1988).

*This article was originally published by The Rafu Shimpo on March 27, 2016.

© 2016 Mary Uyematsu Kao