“There were no Japanese Americans left in Juneau at that time. It was a moment when this community came together in an act of quiet disobedience for the injustice of the internment.”

—Juneau resident Mary Lou Spartz

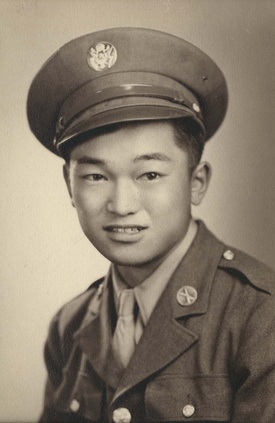

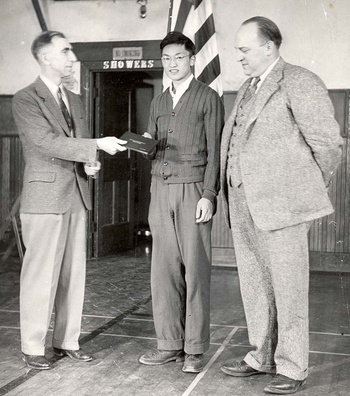

It was 1942. The valedictorian for the Juneau High School graduating class was affable John Tanaka, whose extracurricular activities included yearbook editorial board, honor society, science club, math club, photography club, and quill and scroll.

Unfortunately for John, Executive Order 9066—which authorized the forced removal of US citizens like him away from their homes and businesses on the west coast—meant that he would miss graduation.

The moment to which Mary Lou referred was preluded by the Juneau School Board’s courageous decision to hold a special graduation ceremony for John a month earlier, and resulted in the defiant decision of the graduating seniors to include an empty chair in the graduation ceremony to underscore the absence of their valedictorian. Greg Chaney has wonderfully assembled firsthand accounts of both protests in his documentary film, The Empty Chair, and I strongly encourage readers to view the film to hear details about John’s graduation that are not included here.

Due to the film’s title, the “moment,” and this article’s title (borrowed from the Empty Chair Memorial’s inscription), readers may be quick to conclude that educating viewers about the act of quiet disobedience during the 1942 graduation ceremony is the crux of Greg’s documentary. I urge readers, though, to not make that snap judgment just yet.

Yes, on one level, it is undeniable that the events surrounding John’s senior class graduation are at the heart of this film. And, without making light of the tremendous loss that American families suffered at Pearl Harbor, yes, this film covers the unnecessarily tragic incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII, complete with clips of foolish government propaganda (set against a backdrop of upbeat instrumentals) narrating the arrival of Japanese Americans in camps: “Naturally the newcomers looked about with some curiosity. They were in a new area, on land that was raw, untamed but full of opportunity.”

While those are all worthy reasons for readers to seek out this documentary, to understand the deeper meaning behind the film as the filmmaker intended is to realize why I love this documentary.

To me, there is an important distinction between these two levels of understanding.

As previously stated, on one level, this film is absolutely about the Japanese American experience during WWII. No way around it; and I am confident that viewers will learn a lot: from the forced removal and the severely-deficient camp life to the post-war struggles of families trying to reestablish their roots.

Not surprisingly, sharing the specific Japanese American experience of John Tanaka as well as the general Japanese American experience of displaced families during WWII was dear to the filmmaker:

“I found the story of the empty chair to be compelling from the first time I heard it. I decided on the spot that I would make a documentary about the event. This was a unique piece of history that needed to be recorded from those people who were still available to tell it. Once I began to uncover this dynamic period of history in Alaska, and the Japanese American internment story in general, I felt compelled to complete the project to honor those who lived through it.”

Beyond the heartbreaking Japanese American experience that Greg captures so well, however, viewers will find an underlying universal message that is at once beautiful and timeless. Aristotle philosophized about the very notion back in his day, and it is just as true and necessary in ours: “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Although these days, this maxim is most likely to be applied to successful sports teams or businesses, I would suggest that we need to think bigger, much bigger. I sincerely believe that this principle has the power to transform society (communities).

Using the Japanese American incarceration as a case study, that is exactly what the filmmaker set out to accomplish.

When dissecting this second level of understanding, it is important to realize that the filmmaker’s intention was to transcend any one ethnic group, and focus on the community at large. He even commented that his focus was to portray an American story—not just a Japanese American story—one of “egregious government overreach and…a little town that did what it could to blunt the injustice of the situation.”

At this time, I would like to revisit Mary Lou’s quote at the beginning of this article because it reveals something remarkable considering the country was at war. She describes a community coming together and quietly defying the Japanese American incarceration even though no Japanese Americans lived in Juneau at the time of the May 1942 high school graduation! That has to be a first, or at the very least, extremely rare.

Furthermore, while the documentary details what happened to the Japanese Americans in the years after Pearl Harbor, it can just as easily be described as a powerful film not about Japanese Americans at all but rather the Caucasian Juneau community.

Too often, Caucasians are left on the periphery when recounting the Japanese American incarceration. This film adeptly deals both with Caucasians involved with the forced removal of Japanese Americans as well as those who were spectators.

Regarding the former, the filmmaker expounded, “One stereotype that I did want to dent, if not shatter, was the impact on the people who were ordered to incarcerate the Japanese Americans. In the case of Juneau, these people were lifelong friends and neighbors. Often…in movies or books, the people who show up to arrest the Japanese Americans are portrayed as callous, indifferent military or law enforcement men. In Juneau, being ordered to arrest friends and neighbors left deep scars on those who were forced to carry out the orders.” To that end, the filmmaker interviewed family members of, and individuals who knew, Alaska’s commanding military officer Skip MacKinnon whose son was good friends with John Tanaka and who was obligated to do just that, and regretted it for the rest of his life.

Regarding the latter (spectators), this is where the real beauty of the film lies.

John Tanaka’s sister, Alice, stated that Juneau was a “community in the fullest sense of the word.” Take for example, the Tanaka family. Realizing that Juneau was a mining town, John Tanaka’s father opened his restaurant near the mine so workers could stop at his café on the way to work to pick up their lunches. His father’s loyalty to the community even compelled him to keep his café open on Christmases because he reasoned that his customers would have nowhere to go to eat their holiday meals if he closed.

Before providing further details that support Alice’s statement, I want to draw attention to a word in the fourth paragraph of this article. I deliberately used the word “resulted” instead of “culminated” because I believe Aristotle’s maxim (the whole is greater than the sum of its parts) applies here. Accordingly, I contend that there was not one event that represented the culmination of the Juneau community’s quiet disobedience, but rather a series of acts.

The filmmaker articulates how the maxim applies to his film thusly:

“A reoccurring theme in The Empty Chair documentary is that several small acts of kindness could add up to something profound. The community of Juneau was powerless to stop the war and they couldn’t stop the internment orders but they were able to display several small acts of quiet defiance that let the Japanese American members of their community know that they hadn’t been forgotten. The moral of the story is that even though you can’t stop an injustice, even a small gesture of solidarity can make a difference to those who have been singled out. And a series of small gestures…can add up to make a profound difference. Don’t be afraid to stand up for someone who is being denied their rights, even if you can’t singlehandedly reverse the injustice, your small act could begin to turn the tide.”

To add to the filmmaker’s remarks and to provide further support to Alice’s statement, there was no shortage of small acts of kindness among the Caucasian Juneau community toward the Japanese Americans. Again, take for example the Tanaka family. During the forced removal, the community held an unprecedented special graduation ceremony for John, and a month later, the graduating seniors set up an empty chair on stage during the actual ceremony. During the Minidoka incarceration, longtime Juneau friends sent care packages; and those in certain professions did what they could, such as Juneau attorney Mike Monagle who worked tirelessly to obtain affidavits to help request releases of Juneau Issei who were imprisoned so they could be transferred to live with their families in the Minidoka concentration camp.

When the Japanese Americans returned, though, is when the Juneau community shined even more, if that is possible. In all my years of studying the Japanese American experience during WWII, I have never heard of a community that was so active in helping Japanese families reestablish themselves after the war. I will briefly touch on some of the highlights, but everybody really needs to view the film so they can hear it from those who lived it.

After the war, local businesses went above and beyond to help the Tanaka family reestablish life in town. The grocery store extended credit to John’s dad, the bank gave him a loan, and what warmed me the most was hearing about the people whom John’s dad had unofficially loaned money to over the years drop by the café and pay him back even though John’s dad admitted that he had lost his ledgers during the war. Based on the Tanaka family’s experience and the fact that Japanese Americans were treated equally in the community prior to the war, it is not a stretch to induce that other Japanese families in Juneau were recipients of similar acts of kindness by the Caucasian Juneau community.

What made the Juneau community’s solidarity unbelievably impressive is when you place it in proper context of the reality in which they were living, which the filmmaker clarifies:

“The actual story of what happened in Juneau is more complex and nuanced than we were able to portray in 70 minutes. It’s important to remember that Alaska was a war zone at the time. Imperial Japan had invaded Alaskan territory and bombed Dutch Harbor several times. Racism and hatred against Japanese Americans was at a fever pitch in Alaska and the US in general.”

It was against this backdrop that the Juneau School Board voted unanimously to acknowledge the injustice of the Japanese American incarceration. It was against this backdrop that the Juneau community stood behind their longtime neighbors and friends. Awe-inspiring.

Fast forward approximately 70 years. The Juneau community remains proud of their stance during WWII; and in fact, dedicated a bronze Empty Chair Memorial in 2014. Fortunately, the filmmaker was able to present the documentary to local audiences just before the dedication. “It was an extremely emotional screening with many of the internment survivors present along with family members and a large cross section of the community.”

What a perfect ending to this documentary, to capture the historic dedication ceremony. Consistent with the community’s solidarity during WWII, readers may appreciate that the memorial was not conceived by the Japanese American community. Of course it was completed “with the enthusiastic participation of Juneau’s present and past Japanese American community, but it is a somewhat unique monument in that it was undertaken by people from multiple heritages.”

I would be remiss if I did not mention the editing in this film, which really enhances the storytelling and keeps the viewer engaged.

Telling the story through those who lived it is very effective because it makes the film come to life. Otherwise, using a disembodied narrator’s voice may have translated into more of a dull or at least lackluster educational video presentation.

Also, varying the settings for the numerous interviews did wonders for me. Some were held in the sanctity of people’s residences, some were conducted outside around Juneau. The footage that I especially enjoyed were the ones on location. The filmmaker and John Tanaka’s sister, Alice, who narrated much of the film, visited the area where Japanese Americans were dropped off to board ships away from Juneau. They also visited the Puyallup Fairgrounds, which was their assembly center in Washington.

In closing, the filmmaker reflects on some of his personal takeaways, looking back on the whole process:

“The extremely bittersweet aspect of making this documentary was that when I interviewed people who lived through the events, their grown children were often in the room. These children were often in their late 50s or older and they had never heard about the internment from their parents. In some cases the elders who gave me the gift of their stories have now passed away. If it hadn’t been for the documentary, these people’s stories would have vanished forever.

“When I was in my early 20s I interviewed my grandfather about his life. By taking the time to sit down with him and ask questions, I learned things I never would have known. He died several years ago and I really am glad that I took the time to do that. I realized that talking to your elders and drawing out their stories is one of the greatest gifts you can give to them, yourself, and future generations.”

And while the filmmaker intended his documentary to have a general American audience, if he were to specifically address young Japanese Americans, he would encourage them to “be aware of the extreme challenges their relatives faced and how ultimately they were able to overcome them.” He would also add that “the Japanese American community has also inherited a responsibility to be vigilant to ensure that another group does not suffer the same fate.”

Presently, Greg Chaney is working on a narrative feature film structured around the events covered in this documentary. Additionally, he is always searching for a photograph of the 1942 Juneau High School graduation ceremony. If anybody is interested in backing a feature film derived from this documentary or knows of a graduation photo capturing the empty chair, please contact Greg.

* * * * *

Please join us on Saturday, April 2, 2016, at 2 p.m., as the Japanese American National Museum hosts a screening of the documentary, The Empty Chair, followed by a Q&A with filmmaker Greg Chaney and John Tanaka’s sisters, Alice and Mary. According to The Empty Chair Project website, Empty Chair Committee members will be attending as well. Go to the JANM website to RSVP for the screening.

© 2016 Japanese American National Museum