The establishment in 1947 of a Southern California NAU to oversee a basketball league was a very humble beginning. There were just two divisions: AA and A. Gymnasiums were difficult to obtain. Referees were just as scarce. Often, players from other teams in the league were recruited to officiate. Because job opportunities were so limited, money was in short supply. Honda recalled that most players and teams paid their league fees on a “pay as you go” system at a dollar a week. Team entry fees were $15, and the NAU membership was $1 per player. The referee fees were $1.50 per game. This was a sizable amount of money in a community where so many people were looking for work. What this meant is that only the top players were participating, because it was expensive to field a team. Fewer teams meant fewer roster spots. Local Nikkei businesses sponsored teams, but they were usually only interested in the elite ones.

While the participation level was small, community support was high. Chapman College—then located near Los Angeles City College on Vermont Avenue—often saw its gymnasium filled with people watching AA contests. It was a sign of the times. Most members of the Japanese American community interacted primarily with other Nikkei. Most worked for businesses that serviced the community. Options were few in terms of jobs and entertainment. Basketball games were free (although my uncle complained in a column about the meager response when the hat was passed through the crowd for contributions to help defray league expenses). The details of all of these games were dutifully recounted in the newspaper. This coverage of league games was a major reason for the Nisei to subscribe to the Rafu, and, as it turned out, for the Sansei as well.

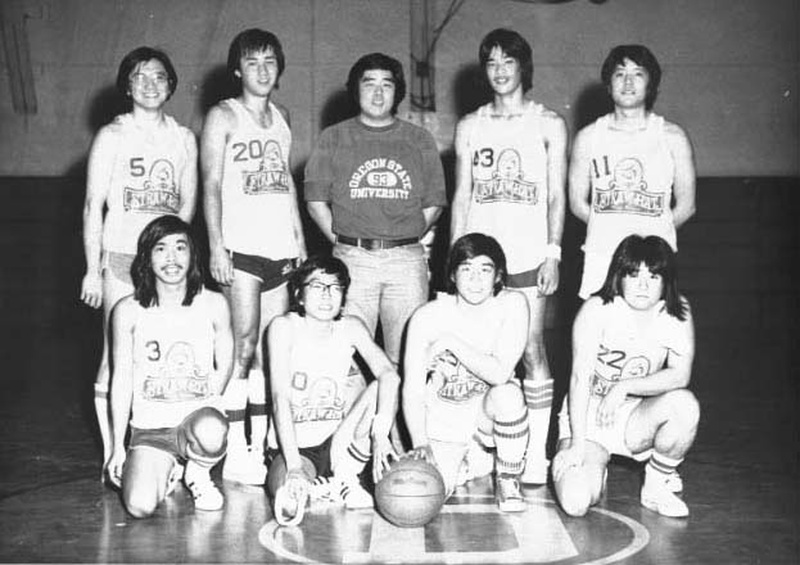

Jump almost 25 years ahead to my first year of play in the NAU. There had been a steady growth in the leagues. NAU had introduced a middle division between AA and A, known as A Plus. In 1971, Southern California NAU consisted of one AA league, four A Plus leagues, and seven A leagues, about 70 teams. The league was going through a transformation at the time as the Nisei players retired and young Sansei athletes took their place. In a way, everything changed in basketball throughout the country in the 1970s: Uniforms. Style of play. Shoes. No one had heard of Nike in 1971.

Moreover, gymnasiums became easier to obtain through the local school systems. And Japanese Americans had more money to spend on recreation, especially Nisei parents on their Sansei children. As the Sansei matured and moved into the workforce, they could afford to finance their own teams. So the two largest barriers in 1947 to widespread Nikkei participation—lack of gymnasiums and lack of funds—had both disappeared. This created opportunities for less-talented teams (like the one I played on) to join the leagues. Southern California NAU thus began moving from an elite league into a participatory community league. In 1947 NAU resembled a totem pole, with the AA division at the top and the A division at the bottom. However, by 1971 it had turned into a small pyramid, with the steady growth of less-talented teams at its base.

By the end of the 1970s, Southern California NAU hit a participation peak. There were 25 different men’s leagues in three skill divisions, which meant that more than 150 teams played regularly. The Southern California Women’s Athletic Union (SCWAU) had formed in 1969 and Nikkei women on about 70 teams competed in five different skill divisions. Given this Baby Boomer generation’s high participation level, it is not surprising to see two decades later that many of their children play Nikkei youth basketball.

It is also not surprising to see many older athletes still playing. Japanese American Masters’ divisions or leagues where the participants are all older than 35 or 40 years of age have grown substantially in the last decade. When I was in my early twenties, I used to see individuals in their thirties, and I wondered why they were still playing, because many of them had lost much of their athleticism. What I didn’t know at the time is that other elements, both on and off the court, would become more significant to me.

Thanks to good coaching and lots of observation, I learned how to be successful in community basketball. The objective of the game is to win and I knew what the key elements were. My teams didn’t always execute those elements, but I knew. And that experience, learning how to win, provided a certain amount of confidence for a young man growing into adulthood. It created a sense of how things actually worked in life.

I also learned that gaining respect as a person was more important than winning respect as a player. I remember hearing a professional coach say that sports don’t necessary build character—they reveal it. Having watched hundreds of Japanese American men and women play basketball, I have seen under the stress of competition their characters revealed. And that’s when it finally dawned upon me that how I acted on the court, win or lose, was a true reflection of what sort of person I was.

I still wanted to win each and every game I played or coached. It would often gnaw at me when we lost. But I also knew that there were many other things more important, and that my actions as a player, a coach, a scorekeeper, or an official would ultimately reveal my character. So I learned to keep my competitiveness in perspective. And learned to enjoy the experience of playing basketball and associating with many others who felt the same way as I did.

That’s why it’s hard to quit playing. Once you figure something out as important as that, you don’t want to leave it. You want to enjoy it. Savor it. Share it. And that’s why I believe so many parents want to pass this down to their children. They know that most of the young people won’t understand right away. Why should they? We didn’t. But, they want to put them in the position to figure it out one day.

Not everyone feels the way I feel. They get different things from the Japanese American basketball leagues. Or they get nothing. That’s the beauty of sports. Take it or leave it. However, for a lot of Japanese Americans—like me—who have moved away from the community, Nikkei basketball has been very important. It gave me the chance to move back.

Will this relationship between the Japanese American community and basketball continue? I make no predictions. There are many questions that only time will answer. I worry that too much of anything can be bad. Playing basketball year round may be too big a burden for young people. It can lead to burnout, so that Yonsei may turn away from the sport. They may not want their children to participate, at least not so intensively. And there is always the question of eligibility. Who is allowed to play, and who is not. And finally it remains to be seen how popular basketball will remain in the 21st century. Baseball was once the most popular game to play and watch. No more. Maybe in 20 years it will be soccer, or some extreme sport that was just invented in the last decade.

For me, I am grateful for what I experienced. I am glad there was some sort of vehicle for me to build relationships with other Japanese Americans. And I hope that the next generations have the same opportunities that were provided to me.

*This article was originally published in More Than A Game: Sport in the Japanese American Community (2000).

© 2000 The Japanese American National Museum