For the millions of Mexicans and

resident muslims

in United States

On the afternoon of December 7, 1941, the news of the attack by the Japanese navy on the North American naval base at Pearl Harbor had already spread like wildfire throughout the American continent. In the United States, Mexico and other countries where a large number of Japanese emigrants and their families resided, a period of great uncertainty, fear and anguish began to be experienced.

-“What will become of us? Will we be deported? Will we be imprisoned?” They were the first questions that the families of the emigrants asked themselves.

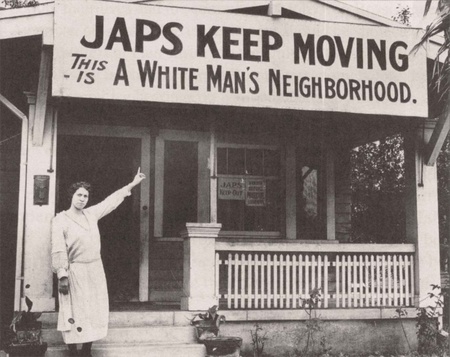

The War of the Pacific had begun, but at the same time a period of persecution and hatred against emigrants in various countries broke out in America. The Japanese attack caused signs of racism and intolerance against Japanese communities, which had already existed for some time, to increase systematically and massively. The adjectives in the press of “treacherous”, “vipers”, “invading army”, “fifth columnists”, “saboteurs” would be foisted without distinction on any emigrant with the purpose of convincing the populations of the measures that would later be taken by the governments in different countries to monitor, deport or imprison all families of that origin.

In the city of Washington, on the same afternoon of that Sunday, December 7, the FBI was working hastily to put into action the first measures against the Japanese emigrants. The agents of that agency in the states of California, Oregon and Washington, where the vast majority of emigrants lived, appeared at the homes of the leaders of the Japanese associations, of Japanese teaching teachers, among others, with the objective to interrogate and detain them. On that unfortunate day, just over 700 Japanese were among the first imprisoned. In the following days, the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, included these states and five others as a “theater of operations” under military control, a situation that, combined with the issuance of Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin Roosevelt in the month of February 1942, allowed military zones to be delimited in which “some or all people could be excluded.” Under these decrees, nearly 120,000 Japanese and their descendants (two-thirds of whom were American citizens by birth) were removed from their places of residence and held in 10 concentration camps.

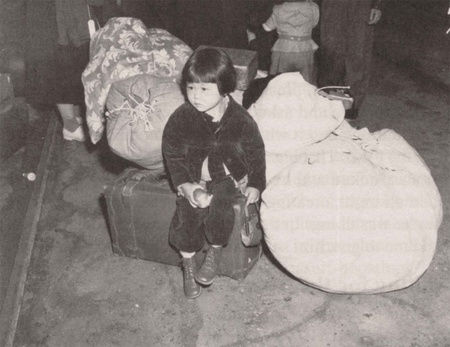

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, most American countries immediately broke off their relations with Japan. However, this measure was not enough for the governments and the war was directed against immigrants who were considered part of the same scenario. The Canadian government decreed to intern nearly 23,000 immigrants in improvised camps. In Mexico, in January 1942, the new year came with very bad news for the emigrants and their families; The authorities ordered them to evacuate the border strip with the United States and go to the cities of Mexico and Guadalajara. Fishermen who lived in Ensenada and farmers who worked in the Mexicali Valley growing cotton were among the first communities to be massively evacuated. Later, from small towns and cities in other states throughout the Republic, thousands more emigrants would leave for Mexico and Guadalajara.

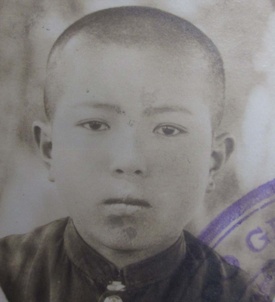

A special case to highlight is that of the fisherman Takeshi Morita who arrived in Mexico at the age of 14 from the Yamaguchi prefecture in 1928. A few days before the war broke out, Morita and his shipmates sailed from the port from Ensenada to capture abalone, lobster and other marine species that were abundant in those rich waters of the Pacific. As they routinely did, without being aware of the Japanese attack, the ship docked in the port of San Diego, United States, to unload the valuable cargo. The entire crew was immediately apprehended by the emigration authorities; The accusation leveled against them was that they were “enemy foreigners.” Without any proof of such an accusation, Morita was sent to the military camp in Livingston, Louisiana, where he was imprisoned for four years despite being a naturalized Mexican citizen since 1935. Takeshi Morita's citizenship did not matter to the authorities. Americans, racial hatred was enough reason to keep the Mexican fisherman detained.

In Peru, the first measures that the government took before the war consisted of the confiscation of assets and bank accounts that the emigrants had; Subsequently, the schools that had been formed by the community itself were closed. However, it is important to note that a year earlier, in May 1940, there was already a strong atmosphere of xenophobia against immigrants in that country. Mobs, incited by the press and sectors of Peruvian society, affirmed that the Japanese emigrants were hiding weapons with which they intended to overthrow the government. The fact was denied by the authorities who, however, did little to prevent the emigrants' businesses and property from being looted and destroyed. The riots cost the lives of 10 Japanese and the destruction of more than 600 businesses and homes of emigrants. Homeless and without a way to survive, more than 300 immigrants were forced to return to Japan, even though many of them were Peruvian citizens.

Many years before the war broke out, the United States already had accurate information on the number and location of emigrants throughout the continent. The FBI had agents stationed throughout Latin America who monitored the Japanese communities very closely to understand the activities they carried out. In the weeks following the outbreak of war, the North American government decided to forcibly transfer more than 2,000 Japanese to North American concentration camps. The detainees came from 13 Latin American countries, mostly from Peru, and although they had no criminal record to justify such a measure, they were practically kidnapped and put on a ship that took them to the fields in the state of Texas.

The policy of racial hatred and mass deportation led to the definitive separation of families, as was the case of Chuhei Shimomura, who was sent from Peru to one of the North American concentration camps. Shimomura was born in the Nagano prefecture in 1910 and, like thousands of young people from that prefecture, he was forced to emigrate due to the growing unemployment and misery that the global depression generated in the silk-producing towns. Chuhei arrived in Peru in 1930 and married a Peruvian citizen, Miss Victoria Ura, daughter of Japanese parents, in 1936.

The marriage produced two children, Flor de María in 1939 and Carlos two years later. The little ones were permanently separated from their father because the emigrant, after his deportation to the United States, was exchanged in 1942 for citizens of the Allied countries. After Chuhei's move to Japan, the family could never be reunited again.

The illegality with which Latin American citizens of Japanese origin were uprooted from their countries, as well as the concentration of hundreds of thousands throughout the continent, was a flagrant violation of their rights under the laws and constitutions of all those countries. In the United States, Min Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi were two of the first American citizens of Japanese origin to defy curfew and assembly orders, which is why they were arrested. Faced with this measure, the young people were dissatisfied and took their cases to the Supreme Court of Justice, which did not agree with them largely due to the pressure of the war itself and the military authorities.

However, in the second half of the 1980s, the cases of Yasui and Hirabayashi were reopened and the malicious conduct of the judges who clearly violated the constitutional rights of these citizens was proven. The Japanese community as a whole managed to raise a great movement based on this resolution and forced the North American government to recognize the series of illegalities that the State committed against its own citizens of Japanese origin. Even to investigate the terrible events faced by the concentration camps, the North American Congress was the one that authorized the creation of a Civilian Internment Commission during the War that concluded that the imprisonment was due to “racial prejudice” and “war hysteria.” ”.

Finally, in 1988, North American President Ronald Reagan signed the reparation decree that granted 20 thousand dollars to each of the concentrates as compensation, in addition to offering them a public apology for the infamies committed by the State itself. Unfortunately, in no Latin American country have governments offered an explanation, much less compensation, for the series of violations that were committed against the basic rights of emigrants and their children during the war.

The mass deportations and injustices to which Japanese emigrants were subjected in America can be re-presented against other immigrant communities. For this reason, the community of Japanese-Americans every February that commemorates President Roosevelt's confinement order does so under the slogan of Never Forget! We must be vigilant to raise our voices against the policies of hate, racism and persecution that are revived with great force in the United States.

© 2016 Sergio Hernández Galindo