Norm Ibuki (NI): From your research, what was it like to be Japanese Canadian in those days before, during, and immediately after WW2?

Dr. Jordan Ross-Stanger (JRS): This is a really big question, and one that I want to be really careful in answering. Japanese Canadians, of course, were very diverse, and the circumstances of their uprooting and internment varied. Internment also changed over time during its long duration. A statistic that I first read in Mona Oikawa’s book, Cartographies of Violence, stands out to me in this respect—2,000 Japanese Canadians were born in sites of internment (one of them our project’s Community Council Chair, Vivian Rygnestad). If we pause over this reality, we can see that no simple answer can be given to the question. Japanese Canadians lived through these events with all of the complexity (including the joys) that would characterize the lives of 2,000 different sets of parents (as well as people in a wide range of other life circumstances), but they also suffered the injustice of the internment in doing so. I’m glad that our project has a robust Oral History Cluster that is exploring memories of these events and linking very textured human stories to the documentation available in the archives.

NI: Any particular stories that you heard that you can share here?

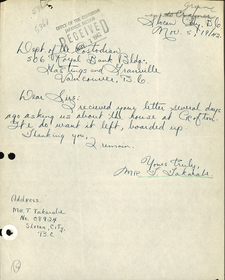

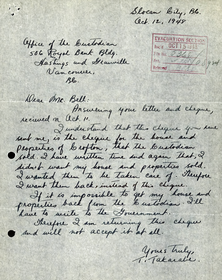

JRS: So many of the stories are powerful. I have been fascinated and inspired by protesters, some 300 Japanese Canadians who wrote the federal government in protest to the forced sale of their property (and the wider policies of the internment era) and whose letters were collected together by officials. I’ve been humbled by the bravery of Japanese Canadians in speaking truth to power, even when their lives remained so insecure. For example, writing on September 5, 1946, Tsurukichi Takemoto forcefully reminded government officials, “[w]e are not Japanese Nationals.” With outrage, she explained: “I did not answer [the notice of the sale of her property] until now because your letter just made me mad enough not to answer… Isn’t the method you’re using like the Nazis? Do you think it is democratic? No! I certainly think you’re just like the Fascists confiscating people’s property, chasing them out of their homes, sending them out to a kind of a concentration camp, special registration cards, permits for traveling [sic]. Don’t you think this is the method used in dictatorship countries? Democracy means no racial discrimination, or is it the very opposite.” Thanks to the initiative of Canadiana.org, this letter, and hundreds like it, are now available online.

NI: How engaged with the Nikkei community and the National Association of Japanese Canadians will you be as you go through this process? What will that engagement look like?

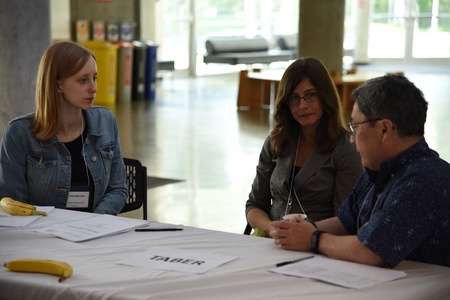

JRS: We’re very grateful for and encouraged by the engagement of the Nikkei Community and the National Association of Japanese Canadians in this project. We are proud of our Community Council, comprised of established and emerging leaders in the Japanese-Canadian community (including, for example, Art Miki). They attend our annual research collective meetings, have a direct line to our Executive Committee and to me (the Project Director), and each is connected with one of our applied research teams for reporting on activity.

We also are proud to partner with the NAJC. Every year we report our work at the NAJC AGM, and they are represented at our annual meetings. Our oral historians (headed by Pam Sugiman, Ryerson University) have conducted community-based workshops in Ottawa and Steveston, and we are hoping soon to connect with local NAJC member organizations for similar events.

Also, the NAJC and Landscapes of Injustice jointly fund a student to work on the project, with the annual $10,000 Hide-Hyodo-Shimizu Research Scholarship. We’ve had superb students win this award and they’ve made great contributions to the project. This year Nicole Yakashiro spearheaded our research on Eikichi Kagetsu, whose lumber company was forcibly sold far below its value. I hope some of your younger readers might consider applying for our scholarship this coming spring.

In addition, Nikkei organizations play vital roles within the research collective. The Nikkei National Museum was a founding partner of the project, and its Director-Curator, Sherri Kajiwara, sits on our Executive Committee and oversees our research in community records, especially those housed at the museum. The NNM will take a lead role in developing our museum exhibit, starting in 2018. We’re also glad to have the support and involvement of the Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall and Toronto’s Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

We’re open of course to further engagement and our researchers across the country are available (without charge) to meet or speak with local Japanese-Canadian organizations. We’re passionate about this work and committed to sharing with and learning from the community most affected by the events we are studying.

NI: How did the project get started?

In conversation. I was researching the dispossession of property on my own and came across others who were interested and engaged. First and foremost, members of the Nikkei community. At the Nikkei National Museum, in particular, Linda Kawamoto Reid conveyed to me significant institutional interest in the same questions I was asking—why was JC property sold? Who was responsible? Who benefited? And beyond the museum I met many other Japanese Canadians (Joy Kogawa, Audrey Kobayashi, Midge Ayukawa, Masako and Stan Fukawa) who convinced me that this story was too big and too important for me to try to tell alone. These conversations soon carried outside of the Nikkei community, to institutions and fellow scholars who were also convinced that the dispossession was an important and enduring event in the history of British Columbia and Canada (Royal BC Museum, Canadian Museum of Immigration (Halifax), Eric Adams, Reuben Rose-Redwood, etc., etc.). Before we knew any better, we had launched a major research project, one of the biggest in the Humanities in Canada today.

NI: How has this story of dispossession affected how the Nikkei community evolved after WW2?

JRS: This is a big question. Of course the dispossession had major impacts, especially, perhaps, on the generation that had worked and saved and built to hold property in 1942. As I mentioned above, I’ve been very moved by a collection of letters of protest, written by Japanese Canadians between 1943 and 1947, in which they forcefully objected to the forced sales and conveyed to officials how much they lost in these thefts of their homes, businesses, and belongings. It is a very powerful collection and is actually freely available online.

Work by scholars who I admire, such as Pamela Sugiman and Mona Oikawa, has explored the ramifications of these policies over multiple generations, showing the very intimate and personal effects of the internment era, even within families that rebuilt their lives so remarkably in the decades that followed. At the gatherings of our research collective (and also elsewhere), members of our Community Council like Mary Kitagawa give powerful voice to the impacts of these policies, inspiring our researchers and our students. It is hard for me to summarize these impacts briefly, but I can quote the words of one Japanese-Canadian property-owner from Haney British Columbia, Rikizo Yoneyama, who wrote federal officials in July of 1944 to explain that the home and farm that his family lost “meant more than just a home. It was to us, the foundation of security and freedom as Canadian citizens.”

NI: Can you please tell us a little about yourself?

JRS: I’m an historian who has been working for almost two decades to understand race and inequality in twentieth century Canada and the United States. As an undergraduate student at McGill University, I wrote an honours thesis on Jewish refugees from Europe who, when they arrived in Canada, hid their Judaism from others, including their own children. As a graduate student, I explored the responses of Italian immigrants and their children to the racial inequalities and spatial rearrangements of North American cities in the mid-twentieth century. Since my appointment at the University of Victoria in 2005, I have written on the efforts of municipal planners to push Indian Reserves out of Canadian cities, the geography of poverty in urban Canada, and now, for the last number of years, on the dispossession of Japanese Canadians.

NI: Can you tell us a bit about your own ethnic background and how it informs your passion as it relates to this project?

JRS: My family is Jewish. Like many in Canada, I grew up with a vague awareness that Japanese Canadians had been interned during the 1940s, but without deep personal connection, or indeed concern, about this history. The informal educational settings of my youth—a blue couch in my family-room where my dad read aloud a biography of Golda Meir, the metal shelves in my grandparents’ basement near Bathurst Street, Toronto, where my brother and I picked curiously through neglected family heirlooms, and the dreary gymnasium of Beth Jacob synagogue in Waterloo, Ontario, where Israeli-accented teachers exhorted us children of the diaspora to understand our roots—the places, in short, where deep connections with the past are forged, pointed me to different histories. It took almost two decades in university classrooms for me to begin to grapple seriously with the importance of the uprooting, internment, and dispossession of Japanese Canadians as events that comprised my own past and the pasts of the students that I was teaching. Still, I cannot remember a time before feeling in my bones an outrage at racism, and my engagement with the dispossession of Japanese Canadians surely grows from those very early lessons about racism as it related to Jews and to my own family. As I look with apprehension around the world today, I’m glad to be doing my own small part to tell an anti-racist history. And I’m very heartened by all of the wonderful colleagues I have found to tell this history with.

NI: Drs Midge Ayukawa and Tom Shoyama had deep connections to UVic. Did you know them personally?

JRS: I never met Mr. Shoyama, but Midge was a great support to this project in its first stages. I met with her several times in her apartment to discuss this history, and she helped me in my early research, particularly as I examined the memoir of Kishizo Kimura, a man who served on government committees overseeing the forced sale of property and about whom I eventually wrote this article.

I often think of a story that Midge told about her mother insisting on taking her stove with her when the family was uprooted. Midge conveyed so effectively her memory of a small but forceful woman insisting (successfully) on being able to feed her family and heat her home, wherever the internment took them. Knowing Midge herself to be a small and forceful woman, I smile to imagine her mother staring-down some RCMP or BCSC employee until she got her way.

NI: I know that you have project members working at all levels of education.

Are there specific learning goals that there might be for university students?

JRS: At the university level, individual professors set their own learning goals, so our efforts are directed at providing them with compelling material in this topic area. We have a number of initiatives that aim to do exactly this. Dr. Sugiman and I have contributed to a widely-used open textbook.

At UVIc, supported by the Community-engaged learning curricular development fund, we are developing a resource that will allow students to engage deeply in LoI research materials and then to create podcasts with material they find important. This resource will be tried-out at UVic first (starting in January 2017), and then shared with professors at universities across Canada.

We are also hoping to develop, in collaboration with the Nikkei National Museum, a virtual exhibit of the letters of protest (above) that would find use in university classrooms.

But the most important way to get this material into university classrooms is to publish material that other professors find compelling and that they might assign to their students. Our researchers are hard at work on this task as well, with materials coming-out regularly in academic venues. You can see some of our publications here >>

NI: What specific aspects of the project is your group working on now? Are there ways that interested JC teachers and community members can become involved in the project?

JRS: We are currently in the research and writing phase. So we’re busy digging into archives, searching land title histories, digitizing maps, and interviewing people to learn as much as we can about this history. We have over a dozen writing projects currently underway that will share our findings with scholarly and public audiences. We also alert the media to our most “newsworthy” findings, in an effort to keep this topic within public discussion and awareness.

To provide just a few examples, our researchers are currently writing work that will: (1) explain the importance of the promise to protect the property of Japanese Canadians, which the federal government made in 1942; (2) detail the relations between Jewish Torontonians and Japanese Canadians in the 1940s and 1950s, when the latter resettled in large numbers in the city; (3) trace the life-paths of Japanese migrants to Canada, including their acquisitions of property and their subsequent dispossession and internment.

We are always looking for new ways to connect our research with members of the Japanese-Canadian community, including teachers. We would certainly invite your readers to connect with Mike Abe, our Project Manager, at mkabe@uvic.ca. He can add people to our newsletter, if they would like to be informed of all the latest news from the project. He also runs a feature of our project called “Touched by Dispossession” where members of the community are invited to share their stories and to help the public (and the project) to continue learning. We’re open to connecting with, learning from, and presenting to local organizations. Mike can facilitate that too. And we’re open to suggestion. Ours is a long project (ending in 2021) and still evolving. We’d love to hear from your readers about how we can better connect our work with members of the community. Engagement is a priority and a passion for me and for the research team.

NI: What is the importance of the timing of this project?

JRS: The project got its first beginnings around the 70th anniversary of the uprooting of Japanese Canadians and it will end when we are almost 80th years past that date. Like many of your readers, I think these markers are important. One of the aims of the project has been to help to keep the dispossession in scholarly and public discussion, to maintain awareness that these are major events of Canada’s twentieth century, and they retain relevance today. These particular anniversaries (70 years, 80 years) are also significant because they mean that we are in the last phase in which a history of these events can be directly informed by the people who lived through them. We’re privileged to have on our Community Council three people who have vivid memory of this history. Mary and Tosh Kitagawa, and Art Miki gave powerful testimony at our Spring Institute in 2016, making a deep impact on our students and indeed the whole Research Collective. For my part, listening to Mary, Tosh, and Art, I was shocked and outraged all over again, despite the years that I have spent studying this topic. I feel grateful and privileged that the project started when it did, so that this kind of learning can still take place and our entire Research Collective can learn, in that very profound way, just how important this history remains.

NI: Can you please give us some idea of what the project might look like at the end of 7 years and the kind of change it could potentially make?

JRS: At the end of the project, I hope we will have created a powerful museum exhibit, distributed widely-used teacher resources to classrooms across the country, established an enduring online archive of materials for public and scholarly use, written compelling histories of these events, and trained dozens of young Canadian leaders. I hope we will have captured some small piece of public attention, to keep this history a part of how Canadians understand themselves and their country, and to make it part of how they consider and confront the challenges of the future.

I hope that the project is not the final word on these events or these topics, but that it inspires new learning and thinking about this and related topics. I hope that our project contributes to democracy in Canada by encouraging us to be a country that grapples seriously with our most difficult pasts.

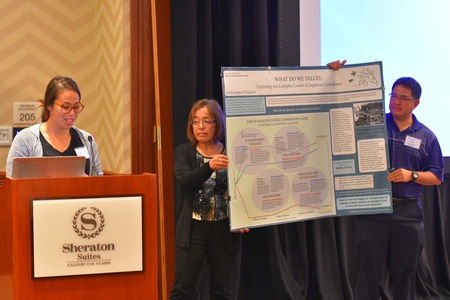

STUDENT PARTICIPATION AND TRAINING

Landscapes of Injustice centres on student participation and training. Approximately 75% of the funding in the project is spent on student salaries and support; every year some two dozen students find employment with us. Students work directly with leading researchers and museum professionals. They do archival research, conduct interviews, design and manage complex databases, translate documents, create maps, communicate across disciplinary boundaries, connect with communities, speak to the media…the list could go on and on. Our students do everything that our project does.

I’m very proud of the training that our students receive. As part of the project, they learn important facets of this history and acquire skills that will serve them in future places of work. They engage questions of social justice, democracy, and activism. They learn how to find their own place within a team comprised of people with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and capacities. Students who are not Japanese Canadian, a majority on our project, learn how to engage historical injustice as active allies—to contribute to excavating harms perpetrated against a particular community while also communicating respectfully with and learning from members of that community. Students of Japanese-Canadian origin have told me that they have discovered new ways of understanding the history of their own families and new people with whom they can explore and interrogate this past. In all, I believe that students acquire important skills while also becoming better citizens of a multicultural society.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki