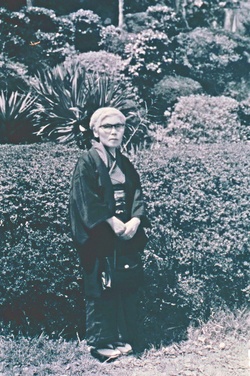

Itoko Nishida, who lived from 1891 to 1987, was originally from Hiroshima-ken before she left Japan to become a picture bride to Kaichi Imada, who was living and working in Vancouver. The Nishida and Imada families lived about 2.4 miles apart in Hiroshima, so when the proxy marriage was complete on October 20, 1910, Itoko was required by tradition to live with her in-laws, Heitaro and Hisa Imada, in the next town.

I thought I would like to go at least once to a foreign land, and insisted. My mother finally relented and gave her permission. It was necessary to hurry and get registered in the family records (koseki), so I entered the Imada family on November 11, 1910.

But unfortunately, Itoko’s father had just passed away, so out of mutual respect, she was allowed to stay with her own family unless the Imada house needed her. A year later, her new husband provided her with money and a passport for her travel to Canada.

I still remember clearly the happiness of that moment. After the wedding, there had been no letter from my husband and neither had I written to him and all I had been able to do was wait. When I think of it now, I think that in the past, farm girls were all like this. The picture bride marriages of 60 years ago were all like that. The young rural women of that era usually left marriage matters to their parents and decisions were made on the word of the marriage brokers. It was handled as if we were material commodities. We just saw the photos and really had no idea what type of men we were marrying.

It was exactly one year after my wedding on October 20, 1911, when I went to the Imada house and on the 21st my Nishida mother came. That night my mother and I slept together. But my mother is said to have greeted the dawn without having slept at all, so full of sad thoughts and tears to be sending her daughter to a far away land. Not knowing parental emotions, I was only of one mind: to go as soon as possible to my husband.

I left by train on the morning of October 21. My husband’s brother had just returned from Canada with his family, so he went to the hotel with me in Kobe and bought me a complete outfit of western clothes.

The ship, a small one, the Canada Maru, made four stops before resting briefly at Yokohama. It was November, the time when the seas are the roughest. We rolled from side to side and not a soul escaped seasickness. It seemed as if everyone had died. I couldn’t eat anything for about 20 days, and only slept.

I wondered why I had wanted to go to Canada when it led to so much misery. I felt even more miserable when I thought that in the future I would have to endure such a trip back to Japan. Eventually we were informed that the ship had reached Victoria and everyone was happy. There was much excitement on board, with some people rushing to the deck and others packing their baggage, forgetting the seasickness that they had suffered.

After the ship reached port and we disembarked (in Victoria), a man called Kuwabara was there to meet us. This person was an interpreter for the Japanese. He led us to the Immigration building. The Japanese who landed were six males and two women—Mrs. Irizawa and myself. Inside the immigration building, everything I saw was completely strange and puzzling. In a large room there were many bunk beds and we were told that everyone was to sleep there. Then a white person who was as big as a giant came into the room and taught us how to use the window blinds. Then this person led us to the toilet. In that era, the water tank was the type that was overhead. There was a chain hanging from the tank and if you pulled this, the water came out. We were startled. It was very strange.

The next day, Mr. Kuwabara came and cleared all the immigration arrangements for everyone. After clearance, the six men and Mrs. Irizawa were taken to the Ishida Hotel by someone who came to fetch them. Mr. Kuwabara said that he had been asked by the older brother of my husband to look after me, so I was taken to Kuwabara’s. At that time there were no automobiles, so the people who went to the Ishida Hotel went by streetcar. I went on a small horse and buggy to the Kuwabara’s.

As I had telegraphed my husband earlier, he came shortly after on November 17 about 10 p.m. How embarrassing and awkward it was. There was no one to even introduce the new husband and wife to each other. My husband’s job at the time was at a Japanese sakaya (saloon) in Vancouver. His job was to wash bottles and put sake into them.

On the 18th, Mr. Kuwabara took us to a church and we were married. It was just a formality and was conducted by a white minister. After shopping and taking care of some business we headed to Vancouver by boat on the 20th.

In those days, most of the Japanese men worked in lumber camps or sawmills and the women living in Vancouver usually worked in the homes of white people. The job was to clean homes and do laundry. Soon after I came to Canada, I too was introduced to a home of a white family by a Mrs. Yamashita who was staying at the same rooming house.

After that I was asked to help at the Taniguchi Hotel, so the female boss and I made the beds, cleaned, and cooked. It was unsanitary. I was shocked at the many lice in the beds where the white men stayed. I encountered these only after I came to this country. At that time, we did not have the convenience of running hot water. We had to use cold water for our cleaning.

Mrs. Imada did this work for only two months in exchange for room and board, and gave it up when she was offered a job doing laundry in a logging camp, a job in which she had limited experience.

At that time, there was a shortage of women so if a bride came from Japan, she received urgent requests from various camps to go and cook and do the laundry. So on February 2, 1912, led by boss Kato, with 13 people who were perfect strangers, my husband and I left Vancouver docks at 3 a.m. We went on a small gas boat to a place called Indian River, and from there got on a small rowboat and after two hours we reached a white man’s camp.

Boss Kato came and said to me that since I am a good cook, it was a waste for me to do laundry here. “I will pay your ship passage if you come with me to Seymour Creek camp. The male cook there is quitting, so I want you to go there and cook.” So reluctantly, since I could not refuse, my husband and I packed our meagre baggage and went to North Vancouver. From there with food and luggage, we got on a two-hour horse wagon ride, went about 10 miles, and reached a place called Seymour Creek.

I came to this camp in August and four months later, I gave birth to a baby girl. It was a difficult experience and I suffered for 12 hours. In this area, there wasn’t a single woman and the doctor was said to be 10 miles away. With no female beside me, in the woods without a doctor nearby, I gave birth like a cat or a dog.

Kaichi had been in contact with his brother and had secured employment north of Nanaimo on Vancouver Island.

We left on December 20. We hiked along the three-mile stretch of bad road, my husband carrying the baby and I the baggage. After one night in Vancouver, we went by boat to Nanaimo and after a day’s trip by train, we reached our destination in the evening. One half mile along a bad road from the station was the shingle camp of Mr. Heiichi Imada (older brother of her husband). Twenty-seven men worked here. I was brought here to cook for these men. This time since I had a child, I did not have to do any laundry, I just cooked. However, 27 people meant a lot of work for a woman with a child, but I worked while weeping. I had to get up at five in the morning.

Mrs. Imada continued living like this for another nine years, moving two or sometimes more times per year, subject to her husband’s whims. She continued to find it difficult to work and care for her ever increasing family, birthing a son in 1917.

After my husband returned from the city, he told me that he had lost all the money gambling. When I heard that the big amount of $1,000 for which I had worked every day like a man from dawn to dusk, leaving my two young children at home, slogging through 4–5 feet of snow, had been all lost by gambling, I don’t know how much I cried. But there were children to look after, so again I went into the woods and worked. I knew my husband’s weaknesses—his love of gambling, his drinking, and his fighting—and told myself that I would have to accept them. I vowed that I would do anything to raise my two children. I worked hard without complaining.

Eventually, in 1922, the Imadas bought land in Haney and settled there, beginning a farm growing strawberries and raspberries. Eventually they expanded to rhubarb, asparagus, white radish, Chinese cabbage, and hens. They built a large home, expanded the farm, and bought a truck to deliver their produce. They tried to grow hops and their five sons worked the farm too. The Imadas even went to Japan on the Hikawa Maru in 1939, on a well-deserved vacation.

In 1941, we decided that we were going to get a bride for my eldest son since he was now 25 years old. Following Japanese custom, many families still arranged marriages for their children in those days. We therefore decided to fix the house from top to bottom. We hired a carpenter and a paper hanger and we bought the best quality furniture for the living room, dining room, everywhere. However, in December Japan bombed Pearl Harbour and the following months were filled with worries, rumors, and problems.

Midge Ayukawa concludes the story by writing “Mrs. Imada and her family subsequently suffered the hardships and indignities of the wartime forced removal of all Japanese Canadians from the coastal area. They chose to move independently to the Caribou–Taylor Lake. Although they eventually lost all their Fraser Valley land (85 acres) and most of their possessions, they managed to survive.”

* * * * *

*Adapted from research conducted by Midge Ayukawa on the history of immigrants to Canada from Hiroshima, Japan, the full translation of Itoko Imada’s story was the basis of a paper in her fourth year at university. The quotes are directly from Midge Ayukawa’s paper entitled “Memories of Itoko Imada.” Compiled by Linda Kawamoto Reid for Nikkei Images.

**This article was originally published in Nikkei Images, Summer 2016, Volume 21, No. 2.

© 2016 Linda Kawamoto Reid