Cherry blossoms made out of tiny white shells. A handcarved wooden vase. A Japanese doll in kimono.

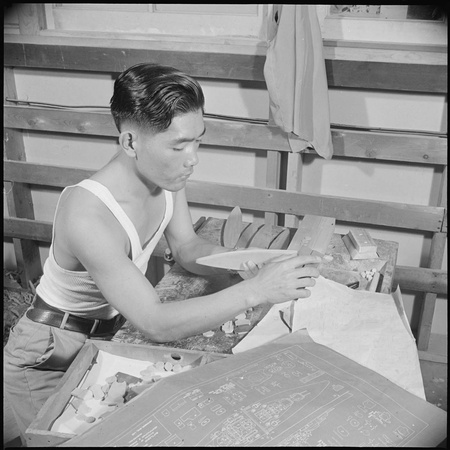

These are some of the artifacts in Handmade in Camp: What We Couldn’t Carry, now on display in the White River Valley Museum in Auburn, Washington through November 6, 2016. The artifacts were handmade by incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II, from found and scavenged materials. The cherry blossoms are made from the shells found in abundance around the Tule Lake site. The wooden vase, from a piece of firewood from Tule Lake. The Japanese doll is made out of scavenged scraps of silk, rayon, and toilet paper.

Guest curated by Seattle Central Community College curator Ken Matsudaira and funded by 4Culture, Handmade in Camp provides a beautifully intimate look into camp history. Matsudaira is a Yonsei whose Bainbridge Island family was incarcerated. “Each item,” he writes in the exhibit description, “is a testament to human ingenuity, craft and courage.” While some of the objects are on loan from the Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle, many more are from private family collections. The majority of objects appear to be made in Tule Lake and Minidoka, two of the main confinement sites where Japanese Americans were sent after their their initial stays in “assembly centers” like Camp Harmony in nearby Puyallup.

Matsudaira is quick to credit museum director Patricia Cosgrove and her staff for the exhibit’s success, stressing that he was most able to assist with its broader tone: “I suggested that the exhibition should focus far less on the act of removal, and instead attempt to portray the years of incarceration that people lived through. The idea was to ensure that the exhibition not only highlighted the artifacts that were made in camp, but also that the human hands that made the objects could be felt as well. Furthermore, we wanted to portray how internees struggled to create a sense of normalcy, struggled to retain a sense of hearth, despite the sparseness of barracks life.”

The exhibit places these handmade objects in just the right amount of historical context, beginning with Executive Order 9066 and continuing through instructions for what each person could take. “Allowed 1 suitcase per person,” a sign reads above a handmade quilt on a bed. An open suitcase on the quilt shows us just how much—or how little— one suitcase holds. Additional historical context comes from Densho’s website and quotes from local Nikkei families, as well as other physical objects: hand-stenciled suitcases, paper identification tags, a copy of the instructions to persons of Japanese ancestry” using local Auburn addresses. For the Handmade in Camp exhibit, the museum has also created a book display focused on the stories of incarceration. Young school-age visitors are given bookmarks with Japanese American names and encouraged to find these names in the exhibits.

Visitors who are interested in Nikkei history will also be interested in several permanent exhibits at the White River Valley Museum, and these are not to be missed. There is an exhibit on the history of truck farming (which many Japanese Americans in the area participated in), and an exhibit called “What Was Left Behind” on Japanese cultural artifacts that would have been left behind during the wartime incarceration. The life-size Issei farmhouse kitchen and the interactive “My Favorite Things” exhibit (for kids) next to it are also well worth a visit. “My Favorite Things” has a dresser filled with Japanese and American artifacts of the Issei and Nisei era, for young visitors to see.

Handmade in Camp has been well received by members of the local community. “I am surprised by the positive and thoughtful reception,” says museum director Patricia Cosgrove. “I say surprised because this exhibit tells a story that is difficult and not positive—not something most of us go out of our way to encounter. That said, we have had steady, good attendance with people coming specially to see Handmade in Camp. By and large the visitors are of two groups, mature Caucasian people who want to learn about this and families of persons who were interned—usually multigenerational.” For Fife resident and Nikkei artist Mizu Sugimura, the exhibit reminds her of family. Her mother and 13 other adult relatives were incarcerated during the war, although they tried their best to put this history behind them. Of those 13 relatives, her mother is the only one still living. “[The exhibit] felt like they were in the room,” she wrote to me in an email message.

Sugimura’s reaction to the exhibit prompted her own family story of a Handmade in Camp” object. “For years a small carved wooden box was tucked into the first drawer of my mother's dresser in my childhood house. I didn't understand why she hid such a beautiful object inside the dresser, rather than to proudly display it as I would on top. As I grew older I came to understand that it was a joint project between her and her dad and it was made in the "camps" where, unlike during her own children, he had plenty of free time to indulge in a father-daughter interaction.”

“There are many people in our area that do not even realize that about ¼ or 1/3 of our pre WWII population was persons of Japanese ancestry,” says Cosgrove. “So even that is a story that should be brought up time to time. Why people left, where they went, and why they didn’t come home are all key parts of that story.” Sugimura adds: “This is why it is such a good thing that institutions such as White River tackle some of the painful threads of our history even in a time of great turmoil—because we can't be expected to move forward on all sides if these things are relegated as they were in the past, to a space under the carpet.”

© 2016 Tamiko Nimura