Slideshow above: Manzanar Classroom Exhibit—Work In Progress. Photos by Gann Matsuda are ©2016 Manzanar Committee. All rights reserved. All materials shown here should be considered to be drafts, not final versions that will be used in the exhibit. Click on any photo to view a larger image.

February 19, 2017 will mark the 75th Anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, which resulted in the unjust incarceration of more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry, more than two-thirds native-born American citizens, into ten American concentration camps during World War II.

Coincidentally, just a few weeks later, Manzanar National Historic Site will mark its 25th Anniversary, having been declared a National Historic Site on March 3, 1992.

Over the last 25 years, the National Park Service has worked to preserve, protect, and interpret the site so that visitors can learn about what happened at Manzanar, dating back to its indigenous inhabitants, the Owens Valley Paiute, through the World War II era, when a total of 11,070 people were incarcerated at Manzanar, which, almost overnight, became the biggest city between Los Angeles and Reno on Highways 14 and 395, as you head north from the San Fernando Valley.

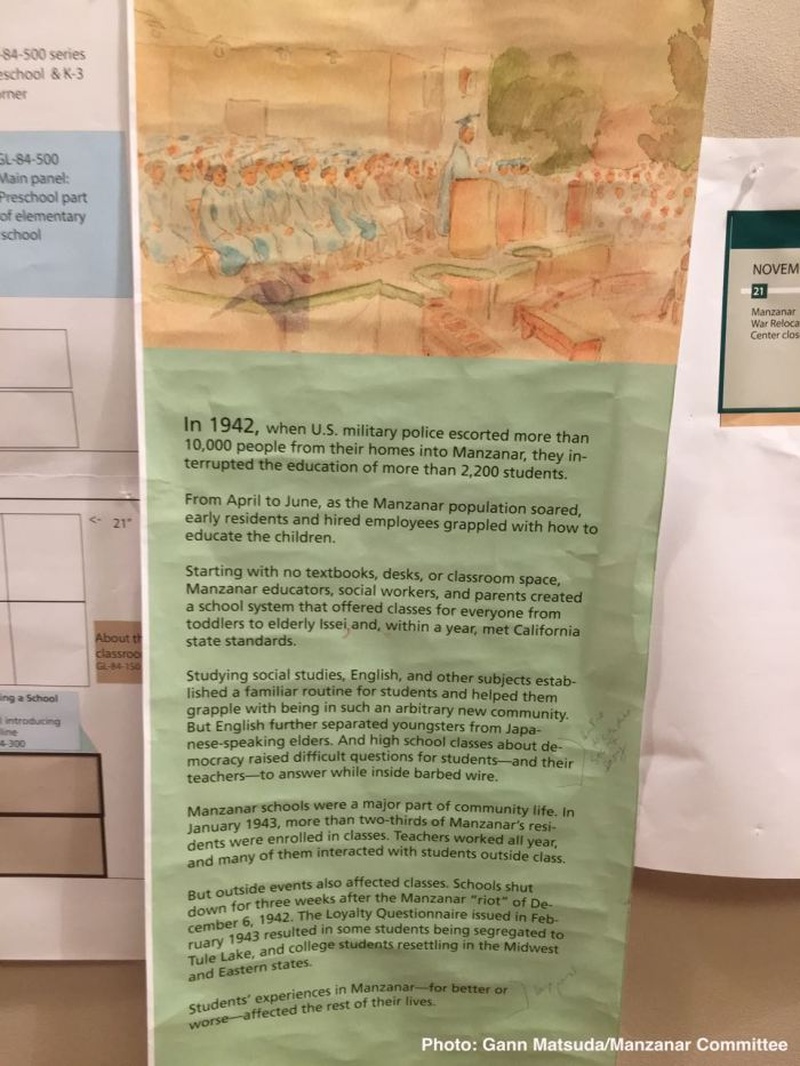

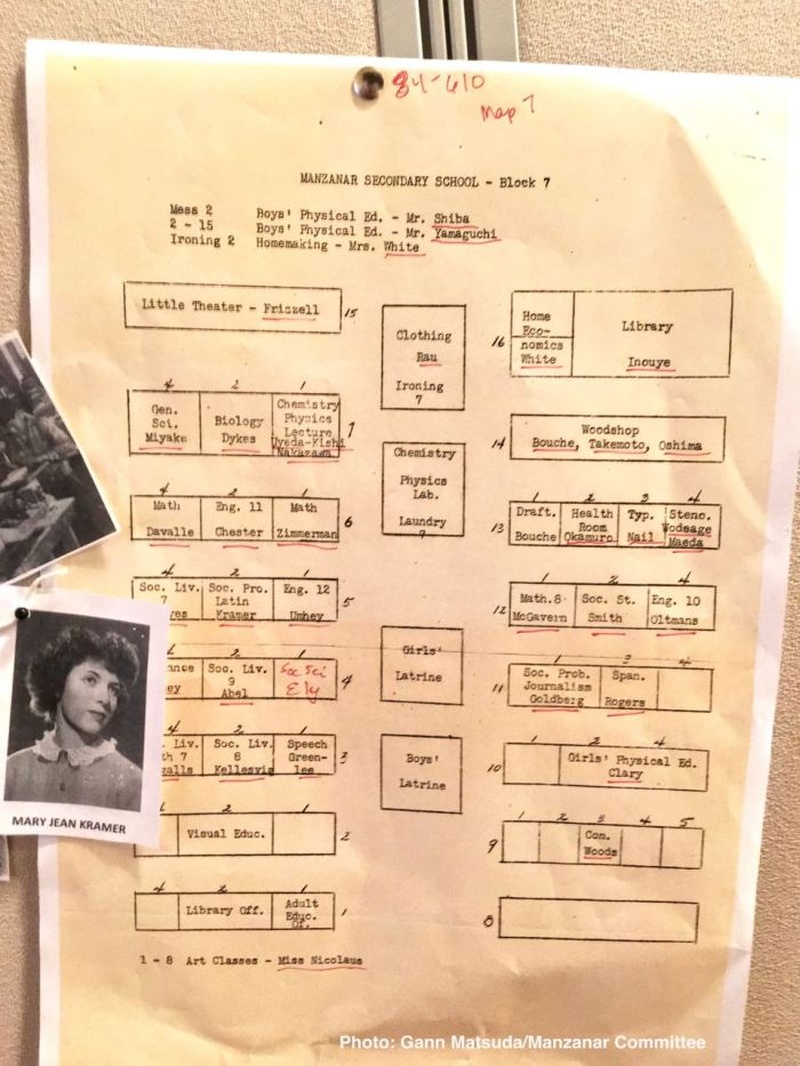

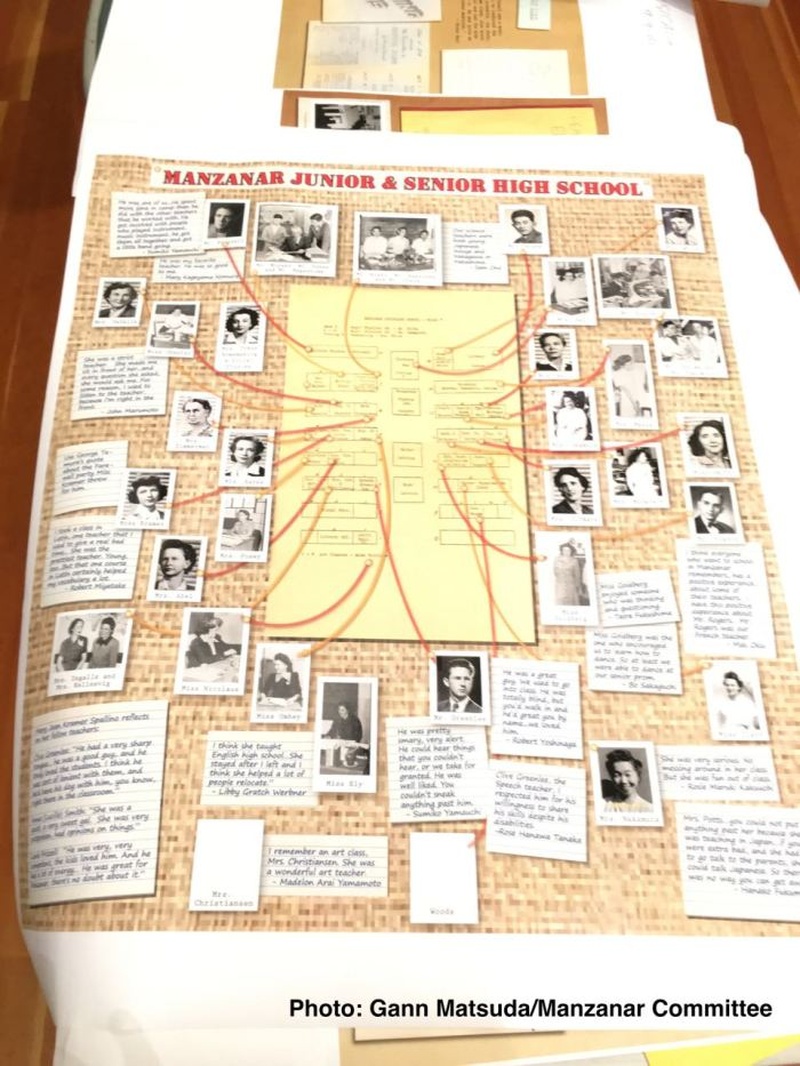

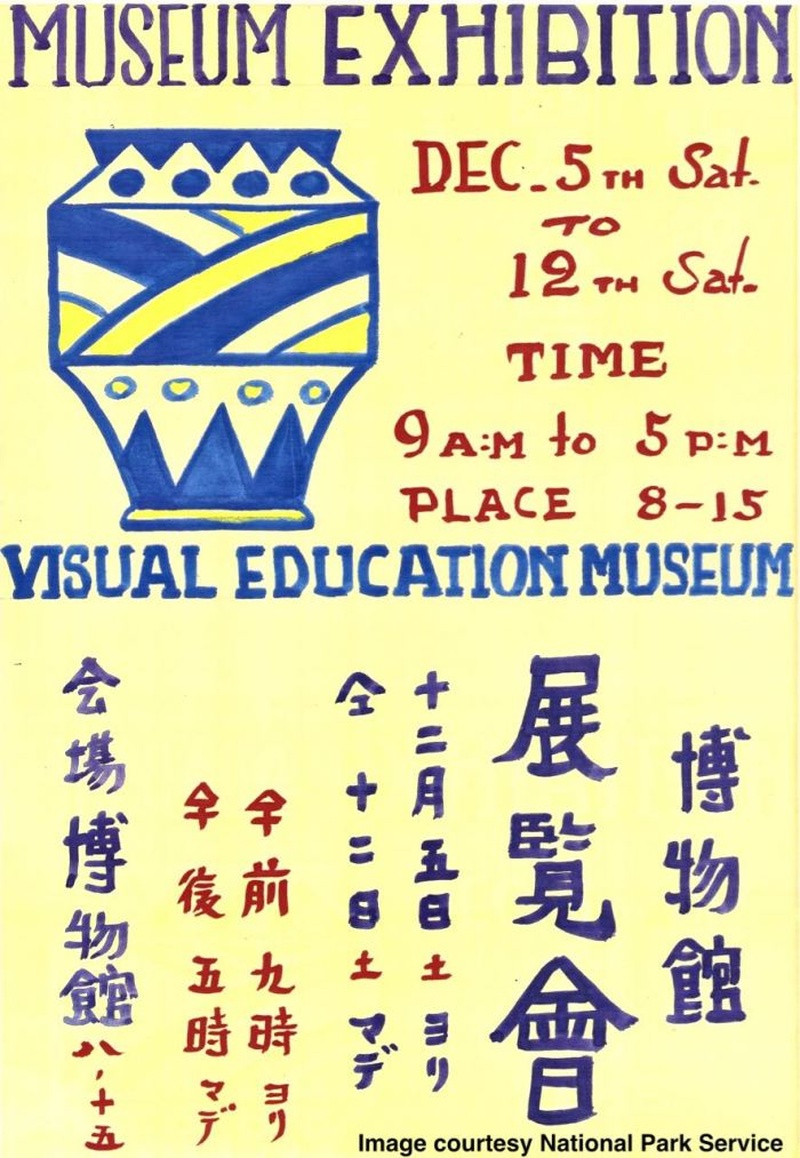

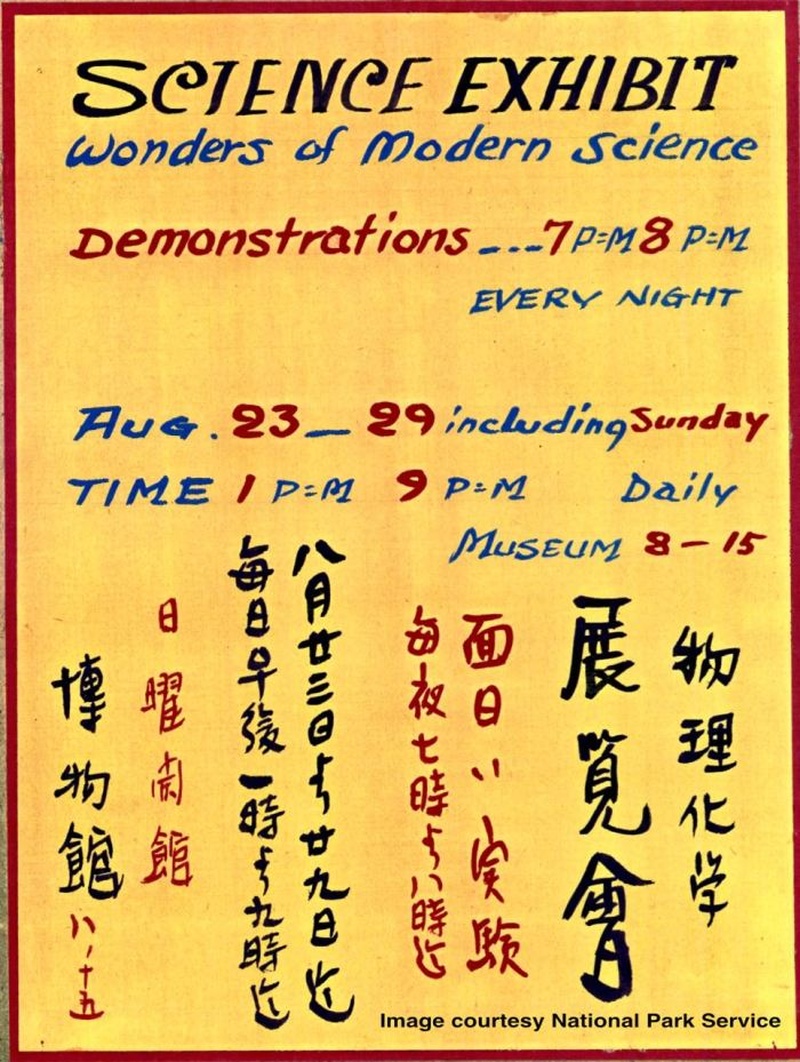

Given that many of the stories about Manzanar and those incarcerated there have to do with the Issei (first generation Japanese Americans who immigrated to the United States) and the Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans who were born in the United States; children of the Issei), it may come as a surprise to many that approximately 7,000 people, from kindergarten through adult, went to school at Manzanar, which will be the subject of a new classroom exhibit, to be housed in the demonstration barracks in Block 14, a short walk from the Visitor’s Center.

The classroom exhibit will join the existing barracks and mess hall exhibits in the demonstration block (Block 14), and will also be joined by an historic replica of the Block 14 women’s latrine (more on that in a separate story).

“I just think it’s really critical that we show the breadth of education here at Manzanar because it clearly was designed to be pre-school to adult education,” said Manzanar National Historic Site Superintendent Bernadette Johnson. “When I think about early education, when kids had no desks, no chairs—there’s a popular photo of kids sitting outside, on the dirt, with textbooks, that had to be so hard for people to come from schools in Los Angeles and then have to endure those kinds of conditions.”

“Especially when I think about 12–13 year olds and how much the social aspect of school is now, and how it’s been for generations, to get dumped into a situation like they did at Manzanar in 1942, it’s critical to show that, but also to show how it evolved,” added Johnson.

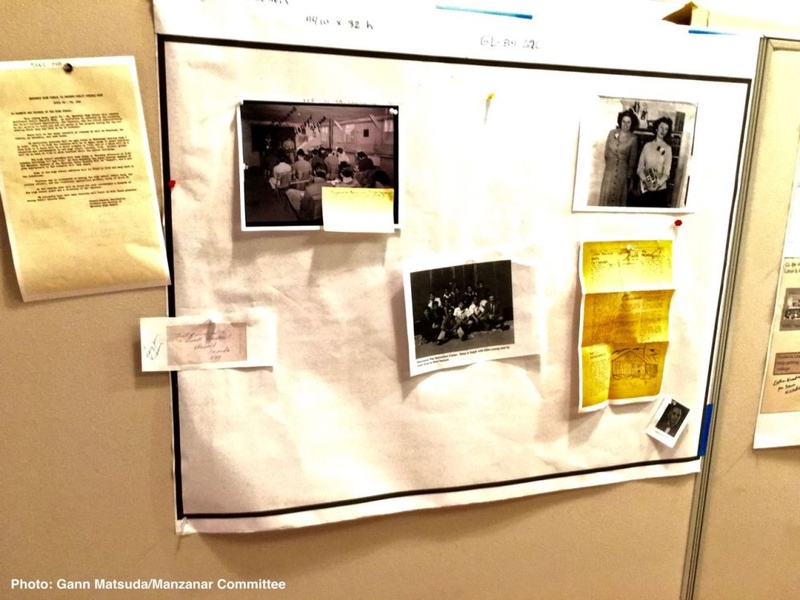

Visitor response over the years has shown that there is a definite need for such an exhibit.

“I’ve actually had visitors at the front desk who were surprised that they had a school here,” said Park Ranger Patricia Biggs. “‘What? They taught these people?’ My reaction was, ‘Yeah. They were not guilty of anything. They were kids and they were here and the adults were not guilty of anything.’”

The exhibit will further efforts at Manzanar to reach more students and to engage them on a whole new level.

“We have a lot of school groups here and a lot of times, they come with a worksheet that their teachers come up with, so we thought it would be nice if we had a place where they could actually sit and write,” said Biggs. “So part of it was just the mix of a pragmatic space that also could be used interpretively, to talk about the kids in school here during the war.”

The school system at Manzanar played a critical role, despite the fact that they were clearly sub-standard.

“The driving, underlying theme [of the exhibit] is that for the people who were forced to be here, their lives were in suspension, in a way,” said Biggs. “They were behind barbed wire and they were gone from their communities, but in another sense, life had to go on, and always, people were aware that they would be leaving camp and picking up with life. To the degree that they could, the Japanese Americans and, to the degree that I’ve found with the white staff, that was in the back of their minds all the time: ‘These people are here now, but we want them to be out, at some point, and be able to pick up their lives again.’”

“Another theme is that you can’t get away from is the fact that they were uprooted and forced to live here behind barbed wire, and especially when they first got here, the conditions were deplorable,” added Biggs. “The U.S. Army, which is the one that started moving people out of their homes, didn’t think about schooling. They didn’t think about anything, other than moving people out of their homes and putting them somewhere to take of the basic needs of life. But as soon as they got here, some of the Japanese Americans, especially those who were here early on—late March and early May 1942—they already knew that they had to take care of each other and get school going, so they started pre-school classes and they started a family welfare program. As new people moved in, they would find someone who had some Sociology training, or just someone who was compassionate to go and find out what families needed.”

Even pre-school age children were served by the school system at Manzanar.

“Genevieve Carter, the white woman who came in as the Superintendent of Schools—she basically asked the question, ‘why have pre-schools in an elementary school,’ because she did pull the pre-school and the nursery into the school program,” Biggs noted. “It wasn’t community welfare. She talked about it being part of progressive education, but she also touched on the reality that the parents were forced into this one apartment with lots of people and who knows what the tensions were going to be like.”

“Reading between the lines, I think she was trying to avoid the frustration of having a toddler under foot who’s crying and won’t nap.” Biggs added. “That’s not what she says, but I look at it as her being very pragmatic, and it’s actually the quote that gives me the highest regard for her because it’s clear that she was thinking that the people were under amazing stress and that they didn’t want them taking it out on the kids or the kids pushing the parents over the edge. ‘Let’s get ’em in pre-school.’”

“When I read her saying that, I thought that does show what I would call pragmatic compassion. She was looking around at this community, and she knew what had happened, yet she was willing to work here. People have different views about that these days, but she was thinking, ‘how do we do this well?’”

Despite the critical nature of the school system, the reality that the students were all unjustly incarcerated was always hanging over their heads.

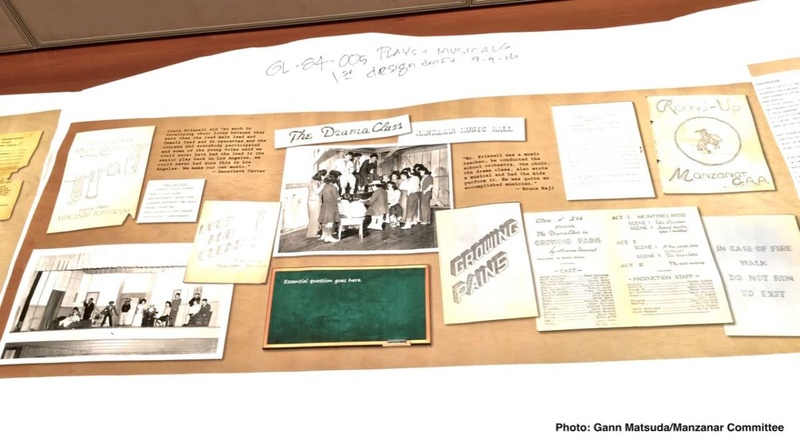

“You’ve got all the normal trappings,” Biggs observed. “Sports, plays, people dating. But you also come back to the fact that the classrooms were in a barrack. Your home is a barrack.”

“There was one teacher, Helen Ely Brill, who wrote in a journal for the American Friends Society, the Quakers, that she was teaching the U.S. Constitution, and the year she was teaching, she collected dimes from the students to help support the four [U.S. Supreme Court] cases [of Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi, Minoru Yasui, and Mitsuye Endo],” Biggs added. “So imagine that you’re a sophomore here and your teacher is telling you about these four cases that are going to fight what’s happening to you right now.”

To be sure, the hypocrisy, injustice, and irony the incarcerees faced at Manzanar were plainly evident in every classroom, every day.

“They worked right away to get accredited with the California school system,” said Biggs. “They worked to get textbooks and they worked with the schools back in Los Angeles to get grades and assignments so the kids didn’t lose too much time. Meanwhile, there was a very real sense that you find under every part of it that they were all aware that there was a very real hypocrisy or irony here.”

“You’re teaching kids—the two main curricula were English and Social Studies and of course, Social Studies talks about democracy, citizenship, and all the things that are so obviously being abrogated, at the time,” added Biggs. “The other thing about English was that they were teaching the little ones English, and they didn’t go to the extremes that the Native American boarding schools had gone to a century earlier. They weren’t telling kids that they couldn’t speak in [their ancestral language]. But they were trying to teach English because they figured that they had to learn English. Meanwhile, a lot of them had parents who didn’t speak any English. So that was a problem.”

While stories about Manzanar’s schools and their K–12 students are known, what isn’t nearly as well known is that adult education and a junior college were also part of the school system. As reported earlier, by January 1943, approximately 7,000 incarcerees of all ages, roughly 2/3rds of the total camp population, were students behind Manzanar’s barbed wire.

“That’s huge, and if you count how many people were employed by [the school system], it touched almost everyone in the camp,” Biggs emphasized. “That’s part of why we decided to add the adult education panel. They also had a serious, fully accredited junior college, which was a part of the regular school system.”

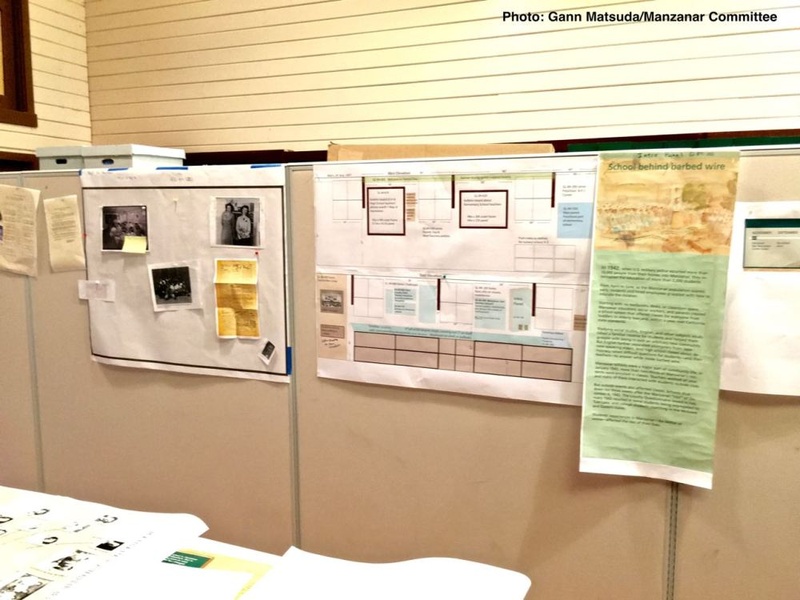

The classroom exhibit is currently in progress, with research and text panel design continuing, with drafts of the panels, a preview of sorts, to be made available in the demonstration barracks sometime in October.

“We intend to have something up in October,” said Biggs. “The desk panels will be pretty close to what they’ll be. The desks have been built. The panels won’t be fabricated [in their final form], but they’ll be on a form board, fixed to the desk.”

“I would be surprised that, if by next Pilgrimage [April 29, 2017], it’s not up and running,” added Biggs. “I think that’s a realistic guess and it’s a great thing to aim for.”

The annual Manzanar Pilgrimage, always held on the last Saturday in April, is the busiest day at Manzanar, in terms of visitation. But annual visitation is on the rise, adding greater importance to the classroom exhibit.

“We have a huge opportunity, with record visitation, to show the many school groups that come here, first-hand, what kids experienced,” said Johnson. “I’m really excited to see this happening. They’re our constituents for the future.”

*This article was originally published on the Manzanar Committee blog on September 22, 2016.

© 2016 Gann Matsuda