After I retired last December, I began thinking of ways to fill my time with purpose. One thing I needed was to begin exercising again after several years of laziness in that department, but I didn’t want to spend big bucks on a gym. Neither did I want to work out in a gym with buff young adults flexing their youthful muscles and wearing sexy workout clothes. Recognizing that I was indeed a senior citizen, I decided to check out my nearest senior citizen activity center in my city’s parks and recreation department.

After assessing the gym where people work out individually, I decided to join a couple of classes for the social interaction as well as the physical benefits. One day I noticed an attractive, petite, white-haired woman all the way across the circle from me. She comes to the class with her walker, but that walker is misleading because she comes to work out with all of us.

I discovered that this lovely woman, Betty Putnam, is a survivor of Japanese internment camps in Canada during WWII. I was immediately fascinated because I love learning about that era. My dad and uncle were WWII veterans, and I’ve always been mesmerized by the photos of my parents and their families and friends from the 1940s. The soldiers were so handsome and brave looking in their uniforms while the young women all looked like movie stars.

I finally got the nerve to ask Betty if she would allow me to interview her and write her story. Since this year is the seventieth anniversary of the end of WWII, her story is a timely one and certainly one to celebrate. It’s also a story from which cultures need to learn the terrible truths about prejudice and bigotry. Betty graciously agreed, so we began our visits along with her daughter-in-law, Carolyn Putnam.

As the three of us sat in Betty’s living room, I began imagining the road that had taken her from Canada to Japan, back to Canada, and then all the way to the United States, where she ultimately settled in Abilene, Texas, a midsize city in West Texas.

Betty was born October 7, 1925, in Vancouver, British Columbia, to Japanese parents. Her parents were first generation immigrants called Issei. The children of Issei, second generation children born in Canada, were called Nisei. The distinction is important because when the war broke out, many Canadians believed that the Issei would be loyal to their mother country, Japan. They were more discriminated against than the Nisei, although the Nisei did not escape the results of that discrimination.

Betty’s parents, Jirohei and Taki Otsuka, had eight children: five boys and three girls. Mr. Otsuka was a porter at the Vancouver Hotel, an upscale establishment that frequently catered to the rich and famous. Mr. Otsuka remembered seeing many stars and celebrities, including Mae West on one of her visits. Mrs. Otsuka was a traditional Japanese wife and mother who did not work outside the home, but her husband and eight children kept her quite busy, washing the family’s clothes on a washboard and seeing to their intellectual and cultural educations. The family followed the traditional Japanese customs while living in Vancouver. Each New Year’s Day, at the request of their mother, Betty and her older sister Tosh bowed to their father and thanked him for caring for them during the preceding year and thanked him for his anticipated care in the coming year. Betty also recalls how she and Tosh wrote letters of “New Year’s Greetings” to their grandmother in Japan, recognizing and respecting her role in the family structure.

Although life was not particularly easy for the Otsuka family, neither was it particularly difficult before the outbreak of WWII. Betty attended a public school for grades one through eight and then a commercial high school for the rest of her education. She learned many secretarial skills, including typing and bookkeeping. Life changed drastically during Betty’s eleventh grade year in school. WWII began, and Betty distinctly remembers that one of her teachers began referring to the Japanese as “Japs” on that day. From that point, Betty sensed that her life would be different.

When the Canadian government declared war on Japan, the men of Japanese descent were sent to work east of Vancouver. The government confiscated their properties and businesses. Those who refused to work for the government were placed in internment camps with strict supervision. Their maintenance was paid for by the sale of their confiscated properties.

The families of these men were moved to relocation camps in various locations in Canada. In total, approximately 22,000 people were moved to either internment or relocation camps. Betty’s family was included in that number. Her father was in internment camps in both Petawawa and Angler, Ontario, while his family lived first in Sandon (1942-1944) and then Lemon Creek (1944-1946). At both camps, Betty served as the camp secretary in a paid position.

In all, the Otsuka children were separated from their father for four years.

When Mrs. Otsuka and the children arrived at Sandon, they discovered a ghost town with only a few remaining citizens. The original structures became the new home for the Japanese residents. The Otsukas along with five other families were assigned third floor rooms in the old Palace Hotel. In all, six families, totaling thirty-three people, were housed there. Betty recalls the crowded conditions and lack of privacy. Everyone had to share one bathroom and a community kitchen. As Betty recalls, they all worked out a schedule so they could live amicably in these conditions.

The British Columbia Security Commission did not provide teachers during the first year in Sandon. The high school students/graduates and university students/graduates taught the younger ones until the second year when the BCSC did hire teachers for the school children.

Betty was always improving herself. She had mastered shorthand, along with other secretarial skills, while in school in Vancouver, where she had completed the eleventh grade. When she moved to Sandon, in order to attain her high-school diploma, she took algebra and French and took correspondence courses in social studies and health. Her skills made her very employable.

After the war ended, the Japanese were not allowed to go back to the west coast. They were given a choice of going to the east or being repatriated to Japan. This was a cruel and unfair choice, especially for the Nisei who had been born and raised in Canada and considered themselves Canadian citizens, not citizens of Japan. Although most of the Issei felt the same loyalty toward Canada as their children, they, at least, had emigrated from Japan and had family and friends from their former lives still living in Japan.

Betty’s boss, Mr. Burns, who was the Camp Superintendent, was so adamant that Betty and Tosh stay in Canada rather than return to Japan that he told them he and his wife would take care of both of them if they would stay in Canada. On a business trip to the east, he went to see Mr. Otsuka in person, hoping to persuade him to decline the repatriation choice. However, Mr. Burns said that Mr. Otsuka was stubborn and could not be persuaded. Mr. Otsuka felt that the whole family needed to return to Japan together, including Betty and Tosh, since neither was married at the time. Additionally, Mr. Otsuka felt an obligation to return upon learning that his mother was still alive, and he, as the only son, was compelled to return and care for her.

At any rate, the Otsuka family chose the repatriation route and returned to Japan. Betty remembers the imposition on her grandmother and the rest of the family in Japan. Here they were, themselves recovering from the war and now all these Canadian family members had returned to them for shelter. Betty recalls how very cramped it was in her grandmother’s home with fifteen people sharing a very small space and inadequate food to go around.

Betty knew that she would need to find work in order to improve their situation. She asked her father to take her to a city to find work, hoping to find something with the U.S. Occupation Forces. Taking a train, they got off at Osaka and walked about a mile up the main street. There they saw a sign that said “Osaka Military Government” (U.S. Occupation Forces) and decided to go in to inquire about possible work. Betty obtained a job as secretary to a Lieutenant Moran with the Labor Department. She was then assigned to a dormitory for the Osaka Military Government employees. Betty visited her family occasionally on weekends during her tenure with the Osaka Military Government, which spanned about a year and a half. When General McArthur released from employment all American and Japanese Canadians over eighteen years of age, once again, Betty had to seek employment. Fortunately, she soon found secretarial work in a Japanese firm. However, she soon became sick with a malaria-like illness that lasted for several months, requiring her to quit her job and move back to the country with her family.

In the meantime, Betty’s former boss, Lieutenant Moran, got out of the military and took a civilian job with I Corps Headquarters in Kyoto. Coincidentally, one of Betty’s brothers, Akira, worked for the Kyoto Railroad Station. Somehow, Mr. Moran got in contact with Akira and asked him to contact Betty to see if she would come to work for him at Kyoto I Corps Headquarters. This event became a significant one because Akira worked with a young American serviceman named Bob Putnam, who was stationed in Japan and was assigned to the Kyoto Railroad Station.

Destiny is a whimsical thing. Here was Betty in Japan as a foreign national because she was a Canadian citizen who had never planned to live in Japan. And here was Bob Putnam, a Texas boy stationed in Japan. As fate would have it, Bob became interested in Akira’s sister, Betty. At first, Betty was hesitant to date an American serviceman, but her brother finally persuaded her that Private Putnam was a nice guy and that she should go out with him. This date led to a lifelong relationship between Betty and Bob.

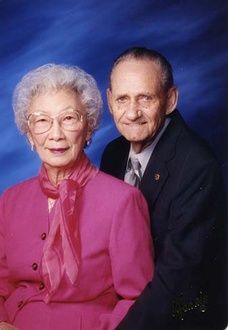

Bob made a career of the Army, so after he and Betty married in Toronto, Ontario, in 1952, they were stationed at many different Army bases including Germany, California, Texas, and New Mexico. Betty and Bob had a son, Robert, and when Betty’s brother, Akira, died in Japan, Betty and Bob adopted Betty’s three-year-old nephew Kiyokazu (now named Kenneth). When Bob retired, the Putnams moved to West Abilene, Texas, in order to be closer to Bob’s mother, who lived in Olney.

When Betty first accepted my invitation for an interview, I expected to hear some harrowing tales of discrimination and prejudice with at least some residual bitterness. That is not what I got. Betty’s attitude is one of grace, thankfulness, and acceptance. When I asked her how she could be so forgiving and understanding, she replied, “What good would it do to be angry?” Her mother evidently instilled in her children an attitude of hard work and perseverance regardless of one’s situation.

Betty said that wherever her family was placed, her mother set up housekeeping and got on with the job at hand. Betty absorbed her mother’s attitude of hard work, determination, understanding, tolerance, and forgiveness. The WWII generation is growing smaller and smaller with the passing of time. What a blessing these people can be to the younger generations as they teach them lessons from their experiences!

© 2015 Nancy Patrick