On the night of April 21, 1977, fourteen armed men wearing civilian clothes went to my dad’s office and took him and another lawyer. They put him in the back of a Ford Falcon (the chosen cars of the military/police) and they sped off—that is what some witnesses said.

That evening my mom Beba, my little brother Leonardo, and I were in our eighth-floor apartment on Acoyte Avenue. Something was boiling on the stove. The table was set, but I don’t remember having dinner that night. There was something going on. My mother was nervous and she was not saying much, which was strange since she liked talking to me a lot.

I was sitting on the couch wrapped in a blanket and watching television. I just knew, even though my mother didn’t say a word, that we were waiting for my dad. She kept looking at the clock and I kept staring at the white door hoping to hear the key turn. We heard the elevator stop and the squeaky noise of its metal door opening. We ran for the front door, threw it open, and saw that it was just our neighbor. We said hello to him and went back inside. I was falling asleep, so Beba told me to go to bed.

Suddenly my mother woke us up in the middle of the night. We had to leave in a hurry to go to my Italian grandparents’ house. I was five years old and my brother was two. I knew right away something was very wrong. My mother was crying and I had never seen her cry before. My granddad Juán tried to calm her down. He told her that they would go to look for my dad.

After a while they came back emptyhanded. We moved in to my grandparents’ house so they could help take care of me and Leo while my mom continued to look for my dad.

If you were not living in Argentina in the 1970s, you might not know about the desaparecidos, the “disappeared,” a hallmark of the darkest and most vicious period in Argentinian history. Everything was done silently and citizens didn’t know how bloodthirsty their own government was until it was too late—until their loved ones were caught, tortured, and killed, and their bodies were never found, made to disappear forever. They could not even be grieved over because they were not alive nor dead; no remains meant there was no crime. The victims were silenced, their voices and thoughts taken away in the blink of an eye.

During the 1900s, Argentina endured six coups d’état. The last one, on March 24, 1976, was the worst, resulting in massive human rights violations and the installment of a military dictatorship. The Peronist government, which had been voted in by the people, was overthrown. The new regime gave its “president” full executive and legislative powers. All laws would be passed by decree and the Constitution was now a thing of the past.

If you think about the United States’ Bill of Rights and reverse it completely, you’ll get an idea of what the Argentinian people’s rights were. Citizens lost freedom of speech, freedom of expression, freedom to petition the government, freedom of assembly, freedom to join a party, and freedom of the press, among other liberties. All workers’ rights were suspended, “dangerous” books were burned, and the Supreme Court and Congress were dissolved. Most significantly of all, more than 30,000 lives were lost in very tragic ways.

This may sound fantastic to you, like a work of fiction, but there is a fine line between possibility and reality. Since man is the same everywhere, what happened in Argentina could happen elsewhere if we are not vigilant about our collective history as human beings.

The dictatorship eliminated any opposition by using state terrorism. Violence was the norm, not the exception, employed to maintain power over citizens. Many methods were used to keep up this “social discipline,” as they called it: fearmongering, censorship, surveillance, exile, incarceration without trials. This state-sanctioned violence culminated in the establishment of secret detention centers throughout the Argentinian territory where citizens could be taken against their will, interrogated, tortured, killed, and either buried in mass graves or thrown out of an airplane into the Río de la Plata.

This phenomenon of the “disappeared” or desaparecido was the military dictatorship’s attempt to erase undesirable people’s identities, histories, and what they stood for. You might think political situations won’t touch you, but when they do, they have a huge impact; overnight, you can become the protagonist, not just a spectator. This is how it happened to my family.

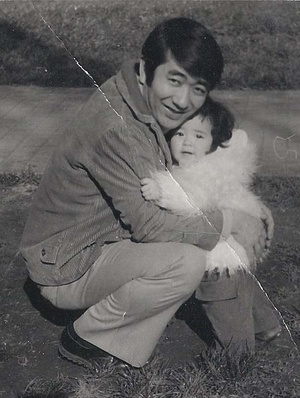

Oscar Takashi Oshiro. You probably don’t recognize this name, nor does he mean much to you. But for me and my family, he meant the world. He was my father. He married Edvige “Beba” Bresolin and had two kids, Leonardo and Gabriela Oshiro. He was 36 years old when he was abducted on April 21, 1977.

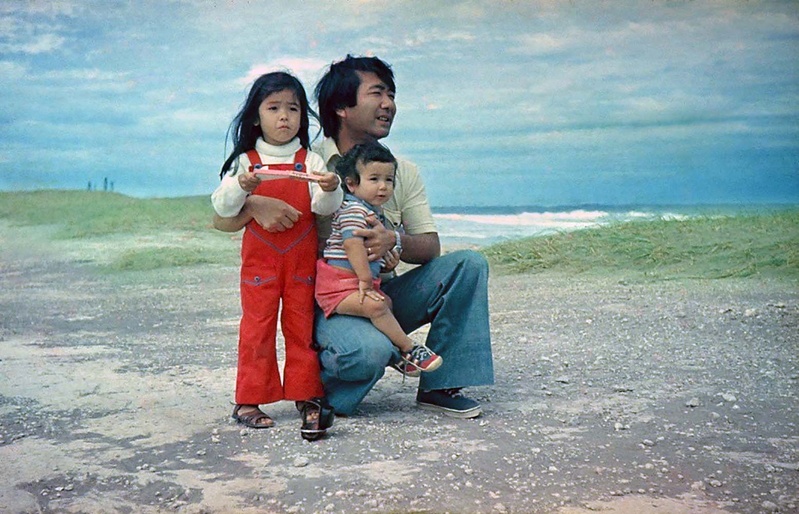

We were a typical family—my father worked, we took summer vacations on the beach, we were surrounded by loving relatives, we had deeply held beliefs, we had dreams.

Perhaps not so typical, and something that I didn’t notice at the time, was the fact that we were a mixed-race family. This was not common in the Argentinian Nikkei community of the 1970s. But my dad, like the sixteen other Nikkei desaparecidos, was odd. He was not a typical Nikkei, even though he had extensive knowledge of Japanese history, language, and customs. He embraced Argentina to the fullest: he loved tango music, he played minor league soccer in the Huracán soccer club—he was even writing a book about the early history of tango when he was abducted.

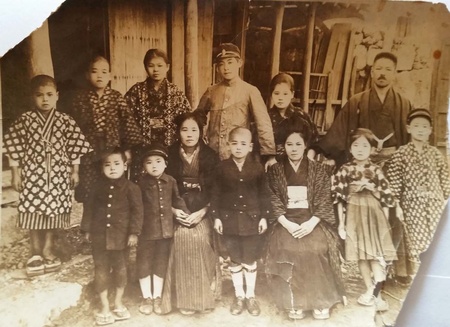

I am not sure what Japanese immigrant communities are like in other parts of the world, but in Argentina, Japanese people came for economic opportunities during the first half of the 20th century. Their main goal was to return to Japan once they had the resources. After Japan’s defeat in World War II, most of the Nikkei in Argentina decided to stay and make the country their home.

They kept a tight grip on their roots, forming close bonds within the Nikkei community. My dad and his sister Yoko went to Japanese language school and attended Japanese events, just like I did with my brother when we were living in Buenos Aires. Most of the Nikkei still considered themselves visitors, so they wouldn’t take part in local politics; they kept to themselves and married among themselves.

Many years later my grandmother Ikuko told me that my parents took longer to get married because my grandfather Katsu was against it—not because my mom wasn’t good enough for my dad, but because she was of Italian heritage. The unwritten rule and tradition was that marrying another Nikkei was the way to go.

But I remember my mother telling me that when she was dating my dad, grandfather Katsu would take them to see boxing matches all the time. They even saw Cassius Clay, aka Muhammad Ali, fight Oscar Bonavena.

My father didn’t care for that Nikkei mindset. He wanted to change the status quo in every way. I don’t think he did it deliberately, falling in love with an Italian, but he had an idealistic enthusiasm that he was going to leave a mark in the world. When I was little, I didn’t really understand this drive; I couldn’t understand why politics and the world around him were so important. Today, however, I can see parallels in my own passion for art and music.

You could call my dad a “hybrid”—he loved both of his cultures and countries equally. He was an avid reader. His thirst for knowledge made him take speed-reading classes so he could consume more books. He spoke Japanese, Italian, and Spanish, of course, and he was learning French. He wasn’t the kind of person to do things halfway; what he preached was what he did.

One of his causes was workers’ rights. When my dad was in his second year of law school, he decided to drop out and get a job at a steel factory so that he could work side-by-side with workers and better understand their struggles and needs. He became the union delegate, but he was let go later on when the workers went on strike.

At that time he wasn’t able to do much to improve the workers’ lives. He had a talk with my mother and she convinced him to go back to law school, because that seemed like the best way to help and give the workers the voice that they deserved. While completing his degree, he got a job in one of the three major labor law firms in Buenos Aires. He graduated in record time and quickly became a notary and a partner in the firm.

His fellow partners at the firm also became his best friends. They saw 30 to 40 factory workers a day, all looking for help; their working conditions were unbearable. My mother told me that the Minister of Economy put in place by the dictatorship was also the owner of the factory that my father was fighting against. Since he was about to win the case, abducting him was the easiest way to silence and delay the verdict.

My dad endured many threats and attempts on his life. For a month, we lived at the Mexican Embassy. My dad was going to get political asylum but a judge issued a habeas corpus, so he couldn’t go into exile. That was pretty much a death sentence. I always wondered what life would have been like if we had been able to get on that plane and start fresh in Mexico.

Certain events become key moments in our lives. In reality, my dad didn’t want to leave; he always said that Argentina was his country. Our extended family was very close, and none of my grandparents wanted to live far away from us. I don’t think anyone knew just how ruthless and sadistic the military dictatorship and their followers really were.

I noticed that many of the other disappeared Nikkei uttered the same words: “This is my country, I am not going anywhere.” Jorge Oshiro (no relation to our family), an 18-year-old high school student at the time, was another desaparecido. He thought that the most the military would do was slap him on the face and send him home to his family.

The dictatorship didn’t look anyone in the face. They didn’t care if the one they were killing was a pregnant woman, a man, or teenager. They put hoods on people’s heads, took away their identities, and assigned them numbers.

Many babies were born while their mothers were in captivity. Their captors would take the babies and give them up for adoption to someone connected to the “cleansing operation.” They thought that being “subversive” (that is what they called anyone who didn’t think like them) was hereditary. They were afraid these kids would come back for revenge. They would forge birth certificates and someone, somewhere, would have a newborn in their household overnight.

Out of the 400 missing babies, 119 have been recovered by the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo* (Grandmothers of May Square). For almost 40 years, they made it their cause to look for the orphaned children born in the secret detention centers. They had a DNA bank to verify the identities. Of course, those orphans are not babies anymore, and it’s a shock for them, to say the least, to learn that their lives were based on lies, and that the adoptive parents, or “snatchers” as they call them, were involved with their biological parents’ deaths.

In Argentina, we are still dealing with the aftermath of the horrific actions committed by the military dictatorship. No matter where you are, who you are, or what you are escaping from—until you deal with it head on, the horror is still going to be there.

*Plaza de Mayo is the square across the street from the “Pink House” where Argentina’s president resides. During the 1970s and ’80s, the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo would protest in silence by walking around the square with white handkerchiefs on their heads that bore the names of the disappeared.

© 2016 Gaby Oshiro