Growing up in a family of voracious readers and three librarians, I was incredibly lucky to have books—almost as many as I wanted. I’ll never forget coming back from our trip to Japan to find that my auntie had left me the entire Anne of Green Gables series on my desk. One day I looked at our family bookshelf and realized that on a full shelf were loaned books that my dad had brought home from the university library where he worked as head of circulation. Some of the most precious books to me were ones that featured Japanese American girls like me. Books by Yoshiko Uchida—Journey to Topaz and Journey Home were (and still are, to my mind) some of the best books about camp; her collection of Japanese kids’ folk tales taught me about Momotaro and Issun Boshi and the Crane Wife.

I’m not sure my father knew much about the need for me to see myself in books, or if he knew about the idea of “mirror” and “window” books. Nancy Larrick’s groundbreaking article “The All-White World of Children’s Books” appeared in 1964, not long before I was born, and the conversation continued. The terms “mirror” and “window” books originally appeared in a groundbreaking 1990 article by the scholar of African American children’s literature, Rudine Sims Bishop. Bishop wrote:

Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.

For many years, nonwhite readers have too frequently found the search futile.

There were many children’s books that I read and loved that were “window” books, showing me life during the Civil War with four sisters (Louisa May Alcott), travel in a covered wagon across the prairies (Laura Ingalls Wilder), even a scullery maid’s garret in early 20th century Britain (Frances Hodgson Burnett). But the simultaneous need to see children like myself in stories is a large part of what made me a reader and writer today. The Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie has a wonderful TED talk about “the danger of a single story,” warning that children who never see themselves in the stories they read may run the risk of having their imaginations—and thus, their futures—“incomplete.”

For my Yonsei daughters, the landscape has changed drastically in some ways. There are many more books in English featuring Asian American, Japanese, and Japanese American children than there were when I was growing up. However, I feel there are still not enough of these books available. I wonder which ones are prominent in bookstores, classrooms, and libraries. Many multicultural picture books are published by small presses with less access to nationwide distribution. Moreover, this year, Frances Kai-Hwa Wang of NBC News quoted Mike Jung, author of the book Geeks, Girls, and Secret Identities. “There’s no lack of window books for Asian-American kids…The lack of mirror books for those kids is profound and unmistakable.”

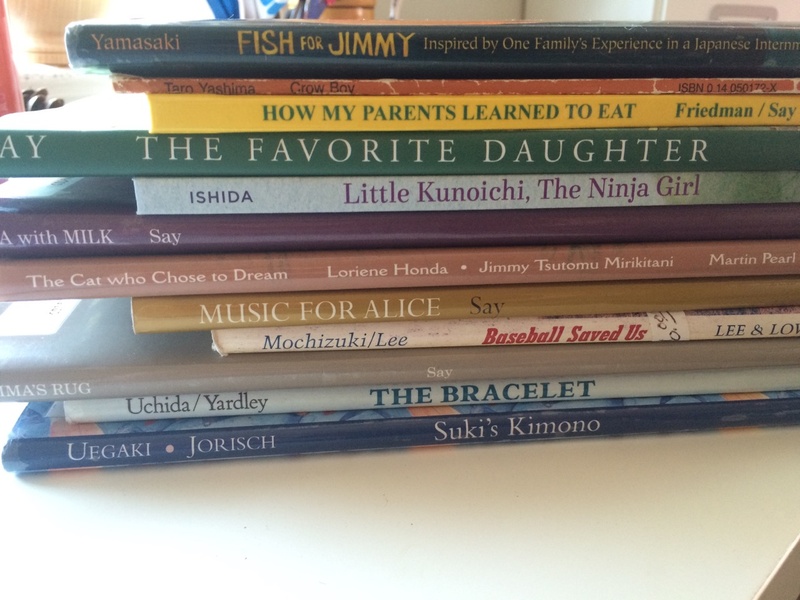

So I have chosen to highlight a few picture books by Nikkei here, ones that I consider “under the radar.” This list is for who want to point the children in their lives to “mirror” books about Japanese American children. And it’s a small tribute to the readers, writers, scholars, booksellers, librarians, editors, and publishers who actively recognize the need for “mirror” books.

Little Kunoichi, Sanae Ishida

Growing up in southern California, Sanae Ishida loved reading books in English and Japanese. Now, raising a daughter in the Pacific Northwest, Ishida noticed the lack of books about strong Asian girls. As a response to this empty space, she created the character Little Kunoichi (Tiny Ninja). Little Kunoichi is a wonderful, whimsical book filled with [beautiful] watercolor illustrations. Little Kunoichi is struggling with her studies at ninja school. But with some hard work and collaboration, she learns the secret of success. My daughters loved Little Kunoichi’s family pet, a ninja bunny, as well as the matsuri scene featuring characters from Japanese folk tales.

A similar fantasy title to try: Sora and the Cloud, by Felicia Hoshino.

The Favorite Daughter, Allen Say

Really, I could recommend so many books by Allen Say. All of his books are beautifully illustrated, and many of them dive deeply into the point of view of a Japanese or Japanese American child. But I chose The Favorite Daughter because it shows a biracial (White/Japanese American) child struggling with name mispronunciation and mockery, which is a common experience for children with Japanese first names in the United States. Eventually, the story’s resolution is largely generated by the child, rather than an outside force, and it’s a creative solution.

Other recommended titles featuring Allen Say’s work: Grandfather’s Journey which won the Caldecott Medal; How My Parents Learned to Eat, with text by Ina Friedman.

Suki’s Kimono, by Chieri Utagaki

Bon Odori is such a wonderful Nikkei celebration that I wonder why there aren’t more books about it. Utagaki’s main character, Suki, wants to wear her kimono on the first day of school because she has such fond memories of wearing it with her grandmother at Bon Odori. However, her sisters and her classmates are skeptical of her choice. Suki must draw on her lessons from Bon Odori and her Baachan to demonstrate the reasons for her choice. Utagaki is second-generation Japanese Canadian and lives in British Columbia.

Other titles to try: Utagaki has also written another picture book: Hana Hashimoto, Sixth Violin.

Fish For Jimmy, by Katie Yamasaki

This title is based on a true story, about a young boy in camp who risked his life in order to obtain fish for his ailing young brother. Yamasaki’s powerful work as a muralist is evident here—there are fish shapes masquerading as clouds, while the shadows in a camp barrack manifest themselves as a guard tower.

Other recommended picture book titles about camp: Baseball Saved Us, by Ken Mochizuki; The Cat Who Chose to Dream, Loriene Honda (with the illustrations of incarceree Jimmy Mirikitani); The Bracelet, by Yoshiko Uchida

Umbrella, Taro Yashima

Umbrella (1958) was one of my childhood favorites. It’s a deceptively simple story about a little girl named Momo (based on Yashima’s daughter) with a summer birthday who can’t wait to use her new boots and umbrella. As a child, I loved the onomatopoeia of the raindrops on her umbrella and I understood the difficulty and pleasure of anticipation. As a parent, I appreciate Yashima’s touching story of his daughter’s early independence.

Other titles to try: Taro Yashima’s Crow Boy won the Caldecott medal in 1955. In a time when so much discussion of bullying occurs in schools, this book may be a useful resource.

* The author would like to thank author Naomi Hirahara and librarian Laurie Amster-Burton for their assistance with this essay.

© 2015 Tamiko Nimura