I’ll always have a special love for Nina Revoyr’s writing. Her 2003 novel, Southland, was the first book I ever encountered by a mixed-race Japanese American woman, not to mention one, like me, with a French last name and a face not obviously Asian. Born in Japan, Revoyr spent part of her childhood in Tokyo and Wisconsin, but most of her books take place in Los Angeles, where she has spent most of her life. She writes about the city with compassion and a sharp eye for detail, paying attention to people and neighborhoods often left out of mainstream stories about L.A.

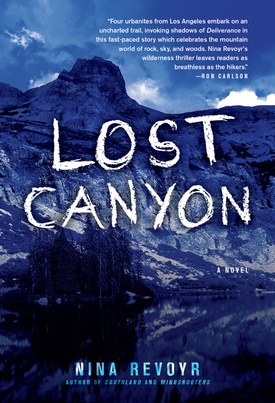

In Revoyr’s latest novel, Lost Canyon (Akashic; 320 pages, $26.95), four Angelenos leave the city for a backpacking trip in its surrounding mountains. There is Gwen, an African American woman who works at a non-profit in Watts; Oscar, a Mexican American real estate agent from Highland Park; and Todd, a white lawyer from Wisconsin by way of Century City. Leading the group is Tracy, a personal trainer who describes herself as “half Japanese, half Irish, and 100% trouble.” The backpackers expect a physical challenge, but when a brush fire forces them to taken an obscure route, they find themselves threatened even more by people than by the natural environment.

I interviewed Revyor once before for Discover Nikkei, when her last novel, Wingshooters, came out in 2012. This time I spoke with her over the phone from Los Feliz, where she will be reading at Skylight Books on September 3 at 7:30 p.m. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

* * *

The Rafu Shimpo: What inspired Lost Canyon?

Nina Revoyr: I love the outdoors, and I really wanted to write an adventure story—kind of an outdoors adventure survival story—but most outdoor adventure stories and survival stories, frankly, involve middle-class white guys, or white guys with particular sets of needs. I wanted to write my own adventure survival story in a way that was reflective of the world as I know it, and that was really reflective of the diversity of my own life in Los Angeles. So I set out to combine two things that don’t often go together, which are adventure-slash-outdoor stories with stories that also take on social and racial concerns.

Rafu: How did you get into hiking and backpacking?

Revoyr: My love of the outdoors is very connected to my Japanese heritage and my time in Japan, my life in Japan, family in Japan, and really the kind of Japanese, and particularly Buddhist, sensibility of the outside, the larger world. I was born in Japan, lived there for part of my early childhood, and then I went back to Japan for a couple years after college. I lived in Nagano-ken—this was before the Olympics—in a mountainous region, and that’s where I started to hike. That’s where I really started to notice the natural world. Then I came back to California, to Los Angeles, and somehow it never really registered that there were mountains surrounding Los Angeles. So I trace my love for the outdoors and particularly mountains to my time in Japan. Then you see these traditions of Basho’s Narrow Road to the Deep North and other writings that really influenced how I think about the natural world and people’s place within it, which in my perspective should be a place of humility and awe and appreciation for the grandness and beauty of the world.

Rafu: There’s so much movement in Lost Canyon—over mountains, across canyons, down one fork of the trail and back. What was your research process like? Did you draw a map to keep track of all these places you were inventing?

Revoyr: The only research I really conducted was spending a lot of time outdoors. When I hike, I really try to take note of the details of the world around me, but also how I feel in those spaces. Many of the very specific descriptions, whether it’s a bird bouncing between the trees or the way that the boulders at the bottom of the valley look like giant snowballs that rolled downhill, those are all observations or analogies that I made when I was outdoors. I often will be struck by something like, wow, the rock is flaking, it looks like a pastry crust or something like that, and I’ll write it down. So it’s not so much research as lived experience and really paying attention to the world I move through. And that’s something I try to do not just in the wilderness but here in the city too. There’s a lot of beauty.

But the second part of your question, regarding keeping track of the places, it is a fictional hike, it’s a fictional route, and certainly many of the particular scenes or vistas or descriptions of valleys or parts of the hike are based on things that I did, but I threw them all together. It’s kind of a greatest-hits. So I actually did, fairly early in the writing of the book, create exactly what you said, almost a fictional map of, okay, I describe them going here. Well, if they had gone here, then the next thing they would do is go here, and this is how the land looks. So I did actually create a map for myself just to not only keep track of places but to keep track of the time passed. You know, all of the action really only happens over three and a half, four days. And yet, as you said, there’s a lot of movement. So that helped me to keep track of everything. And then, after the book was finished, I thought, wow, well we should include a map like that in the book, which is where the map in the book came from.

Rafu: Did you draw that map?

Revoyr: I drew the prototype for that map, but I am the furthest thing from an artist, so I actually found an illustrator who would take what I gave her as raw material and make it look more like it was done by someone who could actually draw.

Rafu: The book travels through different points of view, and we see everybody’s thoughts but Tracy’s. Why did you decide to structure the story that way?

Revoyr: I think there’s a couple of reasons. The first is all three of the others are really embarking on this trip because they have reached a crossroads in their life. All three are essentially early-middle-aged—late 30s, early 40s—and are coping with issues of career, of family, of money, of the physical changes associated with middle age. Things start to break down a bit. Several of them are suffering from injuries. So they are all introspective. They’re all thoughtful. And Tracy’s more a character of action. She’s an adrenaline junkie, she’s interested in risk, she is not always mindful of the seriousness of the situations that they face, and she’s just not the most introspective of the characters. So I didn’t know how much we would get from her. Her thought process would probably be something like “must climb next mountain,” “must see bad guy.”

The other part of it is that I really wanted to play with the notion of the identification of the author with the narrators. And Tracy is the one character who obviously shares my own racial mix. So I think that people tend to automatically assume that the character who seems most like the author on the surface is a stand-in for the author. I kind of wanted to play with that notion and deflect it in a way. Like, okay, here’s this character that you all probably think is me, but actually there’s much more of me in these other characters. You’ve probably heard me say before that the character who is the most autobiographical of all my narrators is Jun, the 73-year-old man in The Age of Dreaming. And that’s another example of really playing with the notion of who the narrator is vis-a-vis the author, because he was probably the one in some ways closest to me.

Rafu: I did think of you when I read Tracy’s description, but as I read on, I realized that it was actually Gwen who shares your work background. You both work at non-profits in L.A. concerned with children.

Revoyr: Yeah, actually, I would say Gwen shares my work background, but the characters I identify the most with, who are probably the most like me temperamentally, are Todd and Oscar. And in some ways, they were the most natural to write because they shared a lot of my thoughts, whereas Gwen shares, obviously, my work concerns, my connection to community, and I think the way she sees issues of race and poverty and kids are similar to mine, but her personality is very different. I think my personality is more like some sort of combination of Todd and Oscar’s, with a little bit of Tracy sprinkled in.

Rafu: Do you feel any anxiety about writing from the point of view of a person of another race?

Revoyr: I think there’s a couple different things. First of all, unless everything you write is complete autobiography—and for me, that would mean each character is mixed-race Japanese and Polish with a French Canadian last name who lived in Japan and—unless every character were that, which they’re not going to be because how boring would that be?—every character is going to be an act of imagination. That’s a given. I also think that what I’m trying to do is reflect the world as I know it. If I only wrote about Asian characters or only wrote about mixed-race Japanese-Polish characters with French last names, that would not be the world that I live in. The world that I live in is extremely diverse. I spend a great deal of my working and social time with folks who are African American, Latino. I’m married to a Mexican American. I also have blue-collar white people in my family. All of these things are influences, and those are the groups that are represented, particularly in Lost Canyon.

I think another point is that I’m a person of color, and people of color, as you well know, have to code-switch in certain ways, have to adapt how we think, how we communicate, based on the setting that we’re in. And I’m also bicultural—I’ve lived in Japan and the U.S.—so I’ve had to do this in a number of ways, and it’s quite natural for me. But there’s different implications. People of color have—or I would hope have—a different kind of entry into writing about other people of color. It’s not the same kind of leap, I think, as when a white person is writing about people of color. But one thing I’m very careful to do, in both Southland and Lost Canyon, is that I don’t ever write first-person. I don’t write first-person from Oscar’s perspective or Todd’s perspective or Gwen’s perspective. It’s always a close third. So that’s kind of like a final leap that I don’t take.

But the main thing is just that this is the world as I know it. It would feel very strange and unnatural and unreflective to me to write books that didn’t include such a mix of characters.

Rafu: As a backpacker, have you ever had a scary experience like the characters in Lost Canyon do?

Revoyr: This book is kind of a greatest compilation of either the misadventures I have had or the misadventures I worry about having. So some of the physical things that occur—like the group gets caught in a thunderstorm in an exposed spot, or at one point a character slides helplessly down an incline, or running smack-dab into a bear—those are all things I have definitely experienced, or someone in my party has experienced.

And then some of the more difficult things, in terms of encounters with other people, I fortunately have not experienced, but the possibility is always there. There are people, a lot of people who—well, I don’t want to give away too much, but there’s a lot of illegal activity that happens in the mountains. And you will often see warnings at trailheads, you know, “Look out for such-and-such.” And there are also a lot of really pretty frightening white supremacist types in parts of rural California. You can go to parts of rural California on either side of the mountains and see Confederate flags or really virulent hate signs or t-shirts about Obama or people of color, and it’s really striking to me that all of these elements of diversity but also elements of racial hatred exist in the same place.

Rafu: Yeah, I drove up to Mammoth recently, and I think it was in Lone Pine where we saw a Confederate flag flying in somebody’s yard near where I was walking around town with my mom—she is my Japanese parent. And people were perfectly friendly, but I’m never more conscious of being a person of color, or especially having a mom who is more visibly a person of color, than in an atmosphere like that.

Revoyr: I have seen that Confederate flag—is it right off the main strip?

Rafu: Yeah, it is.

Revoyr: Yeah, so I’ve probably seen that house. You don’t feel comfortable walking there after dark, or even during the daytime. And if you do some quick research, you’ll see that there’s been quite a bit of conflict between white supremacist groups and some of the Native tribes that are there. The Alabama Hills, which you probably passed, were named after a Confederate warship. And then, interestingly, Kearsarge Pass, which is just out of Independence, just past Lone Pine, was then named by Northern sympathizers. Kearsarge is another warship, but a Northern warship. But there is a history of Confederate sympathizers and white supremacy there, and if you cross directly to the other side of the mountains in Visalia, in that area there is a history of white supremacy there as well, including murders of black people. You can Google this and find it. And when you spend a lot of time in rural areas as I do—and as you saw—you see that. And it’s pretty crazy that you have, again, all of these groups, just tremendous diversity and the tremendously retrograde views on race in the same place.

Because most people in L.A. don’t necessarily encounter these elements, I had a question about whether folks would completely buy the idea of white supremacists in modern-day America. But tragically, recent events in our country have shown that this sentiment is alive and well.

Rafu: In both Lost Canyon and Wingshooters, a main character is revealed to be gay or bisexual only at the very end, as opposed to in Southland or The Necessary Hunger, where the character’s sexuality is out there from the beginning. Is there a reason why you chose to wait in these later novels?

Revoyr: I was trying to be true to who the characters are. I think in Wingshooters, it’s interesting how people read that character because while the confirmation that she is gay as an adult comes at the very end, many readers pick that up from the very beginning. Kind of like how folks respond to—it’s almost like a litmus test—Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, and even some of the questions about Go Set a Watchman were about what’s going to happen with her sexual orientation as an adult. Or something like Fried Green Tomatoes, that couple—see, I was gonna say they’re a couple—that relationship is so obviously a romantic relationship to many people, but others read it as not, as a straight friendship.

So with the Michelle character, I didn’t see that as a surprise at the end and was interested that people considered it so. But in Lost Canyon, I was less trying to make a statement about what the character’s sexuality is or isn’t, and more trying to kind of demonstrate that all possibilities are open—professionally, personally, in her life, as a person—that nothing is closed off to her anymore.

Rafu: You write beautifully about place in all of your books. What are some of your favorite L.A. books that treat place in a similar way, where it is very much at the forefront of the story?

Revoyr: There’s a number of them. I’ve actually been thinking about this recently. I love Walter Mosley’s Los Angeles in the Easy Rawlins books, particularly in Devil in a Blue Dress. What is interesting about him is that people rightly credit him for representing black Los Angeles in a different way. But he also represents a multiracial Los Angeles in a way that is really recognizable to me. Janet Fitch’s books. Really, really vibrant descriptions of Los Angeles. Going back in history, John Fante’s books, Raymond Chandler, Wanda Coleman. It was Wanda Coleman who in many ways gave me permission to write about my own version of Los Angeles. Felicia Luna Lemus, who is my spouse, by the way, her first book, Trace Elements of Random Tea Parties, and just the way that she writes about a particular Los Angeles at a particular era, the writing is so vibrant and alive. Lisa See’s nonfiction book, On Gold Mountain, is just incredible in terms of the detail in the stories, the history, the specificity. Those are some of the ones that come to mind.

Rafu: Lost Canyon is your fifth book. How has the experience of writing changed for you with experience and age?

Revoyr: You had asked me in the last interview which of my books was most fun to write. I think this one was probably the most fun to write. It was just so much fun. It just kind of came out. I had been working on another novel, a historical novel, for two years, and just was so frustrated with it. I couldn’t get anywhere, and I was writing a lot of pages—I had a two-, three-hundred pages—and it was just not alive. I just decided to jettison that book because it wasn’t working, and this idea came to me, and it just flowed so naturally. The characters appeared almost fully-formed. The idea of writing a mountain book, a contemporary adventure survival story, really captured me, and it was a way to get to be outdoors when I couldn’t be outdoors, when the summer was over and I was back in the city. It was so much fun. And I think this is so important—the idea of there being joy in the work. If I’m not having fun writing the book, if I’m not 150% engaged in the story, then why am I doing it? And why would anyone else want to read it? People do talk about how writing is 90% perspiration, 10% inspiration, and for me the inspiration is hugely important. It brings life to the work.

*This article was originally published on Rafu.com, on August 25, 2015.

© 2015 Mia Nakaji Monnier