How did you join the Kodo drummers on Sadogashima?

I first saw Kodo perform at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute in Toronto in 1982. I was completely blown away by their perfection, physical stamina, and spiritual presentation. Since I was only 13 at the time, I never even thought joining them would be an option. However, throughout university, I would see them a few more times and meet the acquaintance of some of Kodo’s performers. By the time I graduated from U of T, and after 10 years in Toronto Suwa daiko, I realized that I wanted to further my studies of taiko and go to the country of my ancestry where it all came from.

How did you apply? What was your reaction to being accepted?

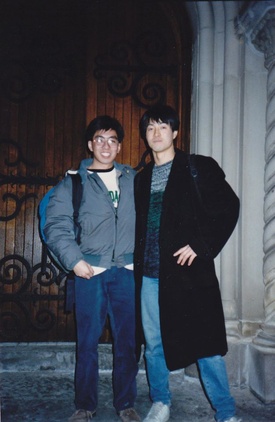

My first attempt to become an apprentice with Kodo was to write a letter to them (translated in Japanese) from Canada. No reply. So, I decided to move to Tokyo to live with my cousin and teach English part-time and to write them again from Japan. After a couple of more attempts, they finally called me back and set up an interview in Tokyo where they were performing. I prepared for the interview, which was conducted in Japanese, by having prepared answers to every possible question I thought they would ask.

Why were you chosen?

I’m not sure why I was chosen except perhaps my determination.

Was being Nikkei a factor?

I don’t think being a Nikkei was a factor. In fact, it was probably a detriment since up until that time no foreigner had ever been accepted as a member of Kodo.

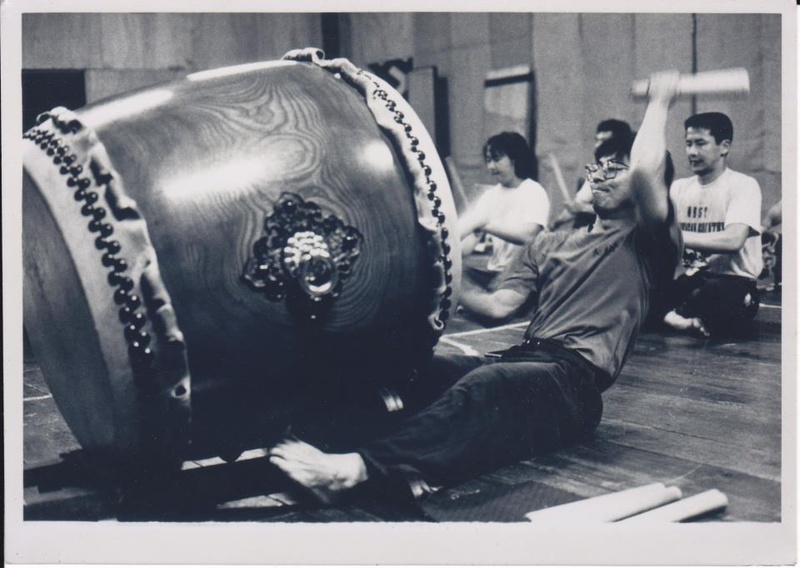

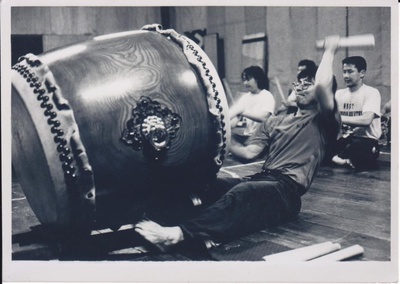

Their lifestyle on Sado is well known for being spartan and very demanding. What was a typical day for you when you were there?

A typical day would be to rise at 4:30 a.m. and go for a 10 km jog at 4:50 a.m. That would be followed by breakfast (prepared by one of the six apprentices on a cooking rotation), cleaning, stretching, and finally drumming from 9 a.m. to 12 noon. Lunch would be at 12 p.m., then more practising from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. That was followed by more individual practise through the evening. This happened 6 days a week for a year. In December, the apprentices ran the length of a marathon as part of the training.

Where did you live?

The six apprentices lived in an old converted schoolhouse by Mano Bay, Sado Island which was about a 45-minute drive from where the main Kodo troupe rehearsed.

What did you eat?

As we had to prepare meals on a tight budget, the diet consisted mainly of vegetables, rice, misoshiru, eggs, and some meat.

Was running part of the regimen? Did you communicate in Japanese or English? Did you go with much Japanese speaking ability?

As I was the only non-Japanese apprentice, daily life was conducted in Japanese although luckily, one of the other apprentices spoke a little English. This was extremely helpful as my Japanese was still only intermediate at best. Nonetheless, I tried my best to communicate in Japanese. By the end of the year, myself and another female apprentice were accepted as probationary members of Kodo. However, I didn’t feel worthy of being accepted and was really struggling with the lifestyle, so I ended up turning down their offer and moved back to Toronto.

Was there ever a point when you thought that you would like to stay in Japan?

Living on Sadogashima was quite harsh and sometimes extreme and I never pictured myself living there long term. However, I did enjoy living in Tokyo and wanted to stay there after returning from Sado but finances were not on my side.

You came back, why?

I came back because I realized that I didn’t fit in with the Kodo way of life and my struggles of not being able to communicate clearly and eloquently in Japanese. I also felt like I could do more good returning to Toronto, and helping to spread the sound of taiko in Canada.

Are you still in contact with Kodo?

I continued to stay in touch with Kodo initially, but over the years, many of the players I knew started to retire. The Kodo today is a much different one that existed in the early ’90s.

Your given name is “Gary” but do you prefer Kiyoshi now?

Professionally, I go by the name Kiyoshi. It’s just a way to separate my professional from personal life. People who have known me up until university still call me Gary. I started using my Japanese name when I moved to Japan, as Gary could not properly be pronounced. People would either refer to me as Ga-ri or Ge-ri (which translates to diarrhea!).

What was the taiko/Japanese music landscape in Toronto when you arrived back? What happened next?

Not much was happening in the taiko scene in Toronto. I did not want to return to Toronto Suwa Daiko, so I decided to play taiko freelance as a soloist. In the first few years when I returned, I helped to form Isshin Daiko at the Toronto Buddhist Church and Do-Kon Daiko in Burlington in 1995. I also formed a cross-cultural percussion and music group called Humdrum featuring Afro-Caribbean, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and Western classical musicians. I also did some work in live theatre and radio.

To me, your music is remarkable in that while it is a very traditional type of music, you have found ways to bridge it with so many other cultures and genres. Your taiko is very “Toronto” in that it represents our great cultural mosaic. How intentional then are these collaborations with Indian tabla, Korean musicians, and others?

Our collaborations with local artists from various cultural backgrounds are quite intentional. Toronto has so many world class musicians of various nationalities that there is almost no need to seek artists from abroad for our collaborations.

Working with local artists allows us more time to work together, less expense, and creates a broader audience base for both Nagata Shachu and the artists we work with.

What kinds of things have you discovered about the possibilities of taiko through these collaborations?

Collaborations have shown me how little I still know of my own instrument!

By working with other musicians, I am forced to explore how to best approach the taiko in order to compliment the overall sound of a piece. Learning how to “feel” pieces that are not from the Japanese tradition is both fun and a challenge. Collaborating with other musicians allows me to refine my own technique and skills as a taiko artist while at the same time, understanding music from a new perspective.

What is the process that you go through during these multicultural collaborations?

Depending on the artist we are working with, the process of collaboration can be quite different. With some artists, we just begin to “jam” together until we find common elements to work with and develop over time. With other artists, we may use an existing piece from their tradition as a starting point to develop a new work. Also, it is not always about trying to find the common elements as a basis for working together. For example, in our recent collaboration with the Toronto Tabla Ensemble, what made it interesting was the very contrasting nature of both our instruments. The taiko is quite loud (played with large drumsticks) and the rhythms can be somewhat primal, whereas the tabla is a very soft instrument in which intricate and complex rhythms are played by the hand. By using these contrasting elements as the basis of our compositions, we ended up complimenting each other’s sound.

What has been the effect on the Toronto/Canadian musical landscape?

I believe Toronto has a much richer and more sophisticated world music scene because of these cross pollinations of traditions. New sounds and compositions are emerging that one would have never imagined in the past and this is very exciting.

Can you talk a little about the state of taiko in Canada in 2015?

The state of taiko in present day Canada is as multifaceted as there are groups in the country. There are many taiko groups that try to “preserve” tradition while others are exploring new territory.

I think it’s all great but my biggest concern is that many groups still lack the basic foundation of the fundamentals of taiko and have little interest or knowledge of the roots of the Japanese drum. Without this in place, it is impossible for any group to preserve tradition or move the art form forward in a meaningful and respectful way.

How has your own taiko changed with time and age?

When I was younger, I could play with more physical power and youthful energy. Now in my mid-forties, I don’t always have the same endurance and stamina that I once did. What I’ve lost in power, I’ve made up in maturity and spirit. I feel that I am able to express myself more articulately as a performer and as a communicator of the music. Over time, I feel as though I have become a more thoughtful musician. I still have a long way to go on my journey, and often wonder how I will approach taiko twenty years or more from now.

What direction is your work moving towards in the next evolutionary phase of your work?

I’ve always believed that taiko deserves to be seen in the same light as classical or jazz music. In order for this to happen, the level of musicianship, compositions, and presentation must be elevated. While my earlier works usually tried to capture the raw spirit and energy of taiko drumming, my more recent works places a greater emphasis on challenging the performers to reach the highest level of musicianship and expression.

Can you please tell us a little about who Aki Takahashi is?

Aki is Nagata Shachu’s most senior member after myself and is the associate artistic director of the ensemble. Not only is she a terrific taiko performer, but is an amazing folk singer and shamisen player. She has composed countless works for the group and has directed a number of our shows. Being from Japan, Aki brings a lot of knowledge about Japanese performing arts and music. Her contributions have been invaluable and Nagata Shachu would not be the group it is today without her. I consider myself very fortunate to have someone like Aki as a member of the ensemble.

Finally, it seems to me that there is something universally “deep” and human about taiko. I’d appreciate getting your thoughts on this.

Because of its deep powerful sound, the taiko is a unique instrument amongst percussion instruments. It has the power and ability to communicate to all people without the need for words or lyrics. You can literally feel the rhythms and vibrations through your body when the taiko is played. I think this is the real appeal of taiko and why there is a taiko group in almost every country in the world. Taiko also has a universal appeal to those who practise it because you must use your entire body, spirit, and mind to make a good sound. I believe many people are drawn to this multidimensional aspect of taiko playing.

Any final words?

Thank you very much for allowing me to share my story. I have been playing taiko for over 33 years and plan to make this my lifelong journey.

For more information, check out:

www.nagatashachu.com

facebook.com/nagatashachu

© 2015 Norm Ibuki