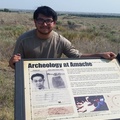

As a volunteer at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), recent developments there revealed that hidden Samurai spirits nestled in the minds and bodies of some of those imprisoned in the US concentration camps that held America’s Japanese prisoners for the duration of World War II. As you will shortly see, that speaks for Tokuichi Muro, a concentration camp inmate shown with his wife, Koito (Funai) Muro, interned in Amache, the War Relocation Authority Center (camp) near Granada, Colorado.

I think, like the Samurai described in Stephen Turnbull’s, The Book of the Samurai: The Warrior Class of Japan, Tokuichi and many of the imprisoned Alien Issei must have felt like “the lone swordsman in battle and the ultimate individual combatant who is also a lover of beauty and nature,” like a Samurai.

It first started to be revealed to me in the Japanese American National Museum's (JANM) announcement of JIDAI: Timeless Works of Samurai Art, an exhibit of Samurai swords and other weaponry, which are now on display for the month of August. In the announcement listing exhibit features, one particular paragraph caught my eye:

“One special piece made in the modern era: a tanto (dagger) secretly forged at Manzanar concentration camp by “Kyuhan” Kageyama, a Japanese American who was incarcerated there during World War II. This artifact is the only one of its kind known to exist, and has never before been displayed in a museum.”

It caught my attention because coincidentally, Jack Muro, son of the late Tokuichi and Koito Muro, who I have written several essays about in the Discover Nikkei website, recently insisted that I accept a short sword that he said his father, Tokuichi “made in camp,” in Amache! So, The Manzanar Tanto may not be “the only one of its kind known to exist,” a sword made in a U.S. concentration camp.

Jack remembers his father unpacking it from their family crate along with all their other family possessions that he and his parents packed for departure and release from Amache, one of ten U.S. concentration camps that held them and upwards of 120,000 American Japanese prisoners for the duration of WWII. Now free from their nearly three-year imprisonment, they were unpacking their Amache crate in the [historic] Boyle Hotel in Boyle Heights, near Little Tokyo in downtown Los Angeles getting ready to begin their new life in 1945.

I emailed key personnel at JANM about this “Muro Tanto,” for want of a better name, to exclaim that there was yet another sword made in camp! They advised me to show it to the Jidai exhibit curators, Mike Yamasaki and Darin S. Furukawa of Tetsugendo.com, specialists in Japanese swords and antiques, who set a date to see the Muro tanto. By then word got out about another “made in camp” sword. So, Masako Koga, long-time JANM volunteer brought up the fact that her son Warren had swords, one of which was made in Topaz by his grandfather, Tokukei Koga. Masako and Warren brought the swords to the curators meeting as well. Masako also brought a photograph of another sword made by Tokukei Koga, but this one supposedly made in the Tanforan Assembly Center and now owned by Warren’s cousin, Tom Koga.

Long story short, the curators were fascinated and very interested in our Amache and Topaz swords, but concluded that our swords, while historically interesting in that they too were “made in camp,” did not meet the requirements to be classified as Nihonto (traditionally made swords), which all other pieces in the exhibition were examples of.

According to Tetsugendo, “True Nihonto should be forged from folded steel with many laminations, and must possess a hand-tempered edge with an actual temper line. While both Amache and Topaz swords were fashioned to replicate the shape of Nihonto, neither were created using the precise techniques that produce a traditional Japanese sword. Though the Manzanar Tanto was made in camp too, it was forged in the traditional manner, just like the other samurai swords that were being mounted for exhibit.” Darin mentioned that should there be a future, larger-scale exhibition, he would like to include our “made in camp” swords for their ironic cultural and historic significance.

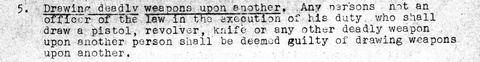

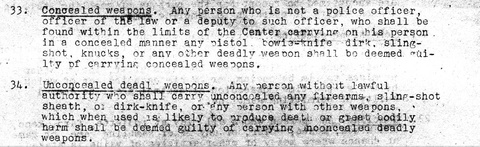

It’s fascinating to think about what inspired and motivated these Isseis to boldly break the obvious prison camp law that surely must’ve been in place against making weapons. Yet, they undertook the challenge to secretly forge steel to replicate the classic weapons of their ancestral forebears. I checked the Amache, 9-pages of Ordinances (laws) governing offenses and punishment. I found three below that related to weapons, but none specifically forbiding making weapons. Obviously, wouldn’t they make it an offense if they only knew about the swords being secretly made? Ordinance 33 might’ve let Tokuichi Muro off the hook being an Amache policeman.

Knives were confiscated in the Tule Lake camp uprisings, but were they just basically shivs or shanks (crudely made prison knives)? In a recently released book “Infamy” by Richard Reeves he cited, “At Tule Lake there were gangs armed with clubs and homemade knives…” Were there any made like Samurai swords?

So, now we know that three, maybe four: The “Manzanar Tanto” made by “Kyuhan” Kageyama, the Tanto blades made by Tokukei Koga in Tanforan and Topaz and the “Muro Tanto” made by Tokuichi Muro were covertly made by Issei concentration camp prisoners. I’m awaiting word from Hiroshi Shimizu, President of the Tule Lake Committee whether there were any others “made in camp,” closer to the quality level Samurai swords and hopefully, this essay may flush-out others.

On the “Muro Tanto” handle made by Tokuichi Muro, he painted the Japanese characters for Ichi, Kokoro, Katana. This was translated by Tomomi Kanemaru, Editor and Graphic Designer for the Nikkan San, the Japanese Daily Sun newspaper as, “One Heart Sword or Sword of One Soul or Spirit” or any such variations she said.I asked Jack Muro whether his father talked about swords or about Samurai. Jack said his dad often touted the qualities of being a Samurai, such as being brave, strong, determined, steadfast, etc., while still appreciating the beauty of nature. Qualities that his father had, said Jack.

Jack recalls that his father Tokuichi routinely read books about Samurai to him after he and his sister, Sakiyo returned to the USA after living with their grandfather in Japan for some years. They were sent to Japan so that their parents could work the farm unencumbered for a time.

Jack holds the photograph showing him and his sister arriving by ship accompanied by their Aunt, who decided to come to America.

Tokuichi Muro, besides being on the Amache police force found time to do fine woodcarvings as well as making the “sword of one heart,” (The Muro Tanto)

I believe “Kyuhan” Kageyama, Tokuichi Muro, and Tokukei Koga were expressing their subdued rage and releasing it through the making of forbidden Samurai swords. Swords which were not intended for violent use, but were made in defiance and reverence as symbols of strength and beauty using their Samurai spirit imprisoned within them. This was how they Gaman (endured).

* This article was revised with the author's request on December 28, 2015.

© 2015 Gary T. Ono