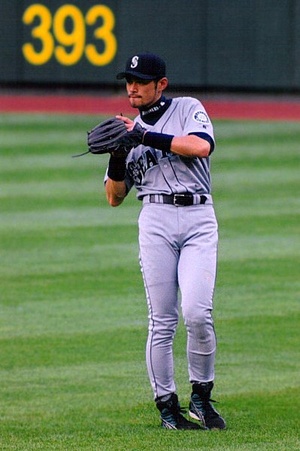

Ichiro Suzuki is easily the most accomplished Japanese baseball player to ever compete in Major League Baseball. The Most Valuable Player and Rookie of the Year in his first season with the Seattle Mariners in 2001, Ichiro is a 10-time All Star who won two batting titles and earned 10 Gold Gloves as the best right fielder in the American League. Before coming to the United States, he won three Most Valuable Player awards in Japan. Yet today, nearing the end of his career at the age of 41, he is laboring almost anonymously as a part time player for the non-contending Miami Marlins. I saw a Marlins’ game on ESPN in which Ichiro started in right field, but batted eighth in the order. The ESPN announcers seemed at a loss at what to say about Suzuki when he came to bat. Perhaps, they were trying to avoid the elephant in the room: now past his prime, why hasn’t Ichiro retired?

When an American superstar athlete nears the end of his/her career with diminishing skills, the sports commentators always ask that question. Why haven’t they quit since they are not performing at a high level and, to many fans, tarnishing their legacy? The three basic answers: they want to win a championship that has eluded them; they cannot give up the sport they love; and/or they want the money. Most American sports fans are sympathetic to the quest for a championship, appreciate a player’s love of the game (until they become totally ineffective), and dislike the idea of someone hanging on for another paycheck. Two-time NBA MVP Steve Nash embodied all of these categories. First he accepted a trade to the Lakers in hopes of collecting the championship he could not win with Phoenix. That dream ended quickly because his chronic injuries made it impossible for him to play regularly. Nash, who is a model of the “right way” to play basketball, continued to work hard to return because of his love of the game, but to no avail. Finally, it was suggested after two futile years that Nash should just retire, but he refused, admitting that he (sensibly) “wanted the money.”

But there is a fourth reason why players continue to play beyond their prime years that applies mostly to baseball: lifetime statistical achievement. Baseball is the one sport where the stats still matter. When I was growing up, the baseball numbers that avid fans knew by heart were 60, 714, 511, 4,191, 56, and 2,130 (in order, Babe Ruth’s single season and lifetime home run records; Cy Young’s win total; Ty Cobb’s hit total; Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak; and Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games played). All of them except DiMaggio’s record have been eclipsed, but the new numbers are still important in baseball. What also still matter are these standards: 300 wins, 600 home runs, and 3,000 hits. Unless you are Pete Rose, Barry Bonds, and others like them, achieving one of those standards guarantees admission into the Hall of Fame.

So, is Ichiro still playing with some thought of assuring his election to the U.S. Baseball Hall of Fame? He is already part of the Japanese baseball Hall of Fame, the Golden Players Club, and most baseball fans think he is a sure thing to do likewise in America. Suzuki had the greatest 10-year stretch by any player in terms of total hits. He led the American League in hits seven times as he averaged more than 224 per season. Two hundred and twenty-four! Cobb, whose career average of .366 is still the highest ever, had only three seasons where he collected more than 224. Rose had only one season where he surpassed that number. Ichiro was 27 when he played his first season in the United States. Compare his hit totals for that decade with both Cobb and Rose for the 10 years after they turned 27:

| Ichiro Suzuki | Ty Cobb | Pete Rose | ||||||

| Year | Hits | Avg. | Year | Hits | Avg. | Year | Hits | Avg. |

| 2001 | 242 | .350 | 1914 | 127 | .368 | 1968 | 210 | .335 |

| 2002 | 208 | .321 | 1915 | 208 | .369 | 1969 | 218 | .348 |

| 2003 | 212 | .312 | 1916 | 201 | .371 | 1970 | 205 | .316 |

| 2004 | 262 | .372 | 1917 | 225 | .383 | 1971 | 192 | .304 |

| 2005 | 206 | .303 | 1918 | 161 | .382 | 1972 | 198 | .307 |

| 2006 | 224 | .322 | 1919 | 191 | .384 | 1973 | 230 | .338 |

| 2007 | 238 | .351 | 1920 | 143 | .334 | 1974 | 185 | .284 |

| 2008 | 213 | .310 | 1921 | 197 | .389 | 1975 | 210 | .317 |

| 2009 | 225 | .352 | 1922 | 211 | .401 | 1976 | 215 | .323 |

| 2010 | 214 | .315 | 1923 | 189 | .340 | 1977 | 204 | .311 |

Only Ichiro had over 200 hits for each of his 10 consecutive seasons. To be fair, I also compared the top 10 hit seasons for the other two, regardless of when they occurred. Suzuki easily topped them both with his total of 2,244 hits, with Cobb next at 2,155, and Rose at 2,114. I even looked up Rogers Hornsby (2,085) and Wee Willie Keeler (2,065). Ichiro compiled, without question, the greatest 10 consecutive seasons for hit totals in American baseball. Ever. Those are Hall of Fame credentials in any country.

So if not the Hall of Fame, what is Ichiro pursuing? Money? He has made over $159 million from his career in America alone and a substantial amount in Japan from endorsements. His love of the game? I wonder. Stories of Suzuki’s childhood highlight his father’s rigorous and almost cruel training methods for his son. “It bordered on hazing and I suffered a lot,” Ichiro recalled. Suzuki, who weighed only 124 pounds when he finished high school, had to work constantly to build his strength and endurance, which sounds like anything but fun. A championship? Ichiro’s Orix Blue Wave team played in two Japan Series and won the title in 1996. He also played on two Japanese National Teams that captured the World Baseball Classic championship in 2006 and 2009. He has not played in a World Series, but if that was his goal, why play for the Marlins?

That leaves his career numbers. If you combine the number of hits Ichiro collected during his nine seasons with the Blue Wave in Japan (1,278) with his current hit total in the U.S. (2,899 as of this writing), Suzuki has a total of 4,187. Only Rose (4,256) and Cobb (4,191 or 4,189 because a statistical study took two hits from him) have more career hits. Granted, Major League Baseball doesn’t recognize any of Ichiro’s hits from Japan, but he collected them against Japan’s best pitchers and it should be clear that the Japanese are able to compete against anybody. He only needs a handful to catch Cobb, which he should accomplish this season. However, Ichiro may also want to reach 3,000 in America. Playing part-time in Miami, that may be out of reach this year. But if he can sign with another team in 2016, he may think he can reach 3,000 and thereby pass Rose.

If this is true, and this is only speculation on my part, it reinforces the conclusion that many sports writers have reached that Ichiro is self-centered and not a team player. That seems absurd on the face of it, because Suzuki is Japanese and the pursuit of individual achievement in a team sport is a cultural contradiction in Japan. Because of cultural values like enryo, the group almost always takes precedent over the individual (See my article, “Too Much Mottainai?” May 26, 2015). On the other hand, one cannot discount the obsessive nature of individual Japanese.

When the Mariners traded Suzuki to the New York Yankees in 2012, Steve Kelley of the Seattle Times wrote a “good riddance” column. Kelley fumed, “In Seattle, Ichiro played the game by his rules. Ichi Rules. He bunted when he wanted to bunt, even bunting on numerous occasions with a runner on second base. And many times, he didn’t bunt when the sign was flashed. Ichiro also often ignored steal signs, going when he wanted to go and staying when he wanted to stay. Too often Ichiro was Ichi-no, and because of that he stalled the Mariners’ rebuilding attempt. Over the years, it became increasingly clear to his managers that Ichiro was playing for Ichiro. He wasn’t a good teammate.”

Bruce Jenkins of the San Francisco Chronicle, in what was a positive story, could not help but note, “The game has known plenty of ‘slap’ hitters, but none who sacrifice so much natural ability for the sake of the art. Ichiro, a man of wondrous strength, puts on impressive power-hitting displays almost nightly in batting practice. The man lives for hits, little tiny ones, and the glory of standing atop the world in that category.”

Wow. If true, this sort of conduct would normally get a player in Japan ostracized. But, maybe Ichiro’s attitude explains why he was willing to leave Japan for America. Like pitcher Hideo Nomo who signed with the Dodgers in 1995, Ichiro was willing to pull up stakes, leave Japan, and find out how good he really was. I was struck by the striking individualism of the current players from Japan after hearing Masanori Murakami speak at a recent event at Whittier College. Murakami, the first Japanese player to succeed in Major League Baseball when he pitched for the San Francisco Giants in 1964 and 1965, ultimately returned to Japan at the behest of his mentor, Kazuto Tsuruoka. According to the story related by author Robert Fitts, who wrote Murakami’s biography, Mashi, “Masanori knew that Tsuruoka expected him to return to the (Nankai) Hawks and felt morally bound to pitch for his old mentor. Besides, after his having spent two years abroad, his parents truly missed him and wanted him nearby.” But Murakami, who enjoyed his time in San Francisco, expressed regret that his baseball career in America was cut short.

Ichiro clearly did not feel the same obligation to stay in Japan or to return to finish his career. Arriving in the United States in 2001, he was met with much skepticism since no Japanese position player had previously succeeded in the U.S. (many Japanese pitchers followed Nomo to America). His thin frame and unconventional batting style added to the pessimism. After cracking 242 hits and earning the Most Valuable Player and Rookie of the Year awards in his first year, Ichiro may have grasped the opportunity before him. No longer shackled by Japan’s social conventions, he was suddenly free to pursue his own goals. It was like a high school graduate going to college away from his home and realizing his parents were not around. Sudden freedom can lead to many things, good and bad. In Ichiro’s defense, his commitment to the Japanese national team has remained robust. In 2009, he was diagnosed with a bleeding ulcer, which a doctor thought might have been caused by the stress of the World Baseball Classic.

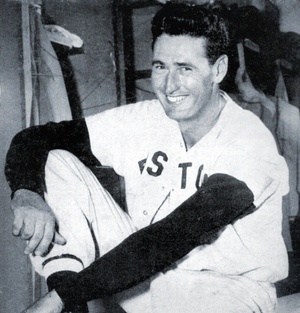

Is Suzuki the first player to be accused of thinking of his own statistics or approach to the game over the perceived team’s welfare? Clearly not. The great Ted Williams was criticized for walking too many times (2,021) when it was thought he should be trying to hit home runs to help his team win. His career on-base percentage was .482, the highest ever and five times it was over .500 (actually, 11 times, it was over .490), but he never had 200 hits in a season. Williams was either principled or hard headed (probably both) when it came to his approach to hitting, refusing to swing at a marginal pitch, despite the game situation. Not surprisingly, he was constantly at odds with certain sports writers and fans and compared unfavorably with DiMaggio for not winning a World Series. Today, with the advent of sabermetrics (baseball statistical analysis) where on-base percentage is highly coveted, many consider him the greatest hitter of the post-World War II era. Hmmm.

To be clear, Ichiro was the opposite of Williams. Only twice did he walk more than 50 times in a season. His approach was similar to that of many of the Latin American players, who grew up swinging at questionable pitches. Scouts often don’t pay attention to batters who walk a lot, so many Hispanic players are very aggressive. Likewise, Suzuki has not altered his approach to hitting as he has gotten older and slower. If he had, he would have been more attractive to a contending team.

Instead, if he stays healthy, he will pass Cobb this year and then he will need to find another team (back to Seattle?) for 2016 in his quest to pass 3,000 and 4,256. It almost seems like a solitary quest, playing in mostly meaningless games (unless the Marlins spring to life). I remember attending a Dodger-Cardinal game in the 1960s when Stan “The Man” Musial was trying to pass the 3,000-hit mark at the end of his career. Getting that last hit was difficult because Musial’s skills had eroded and you could tell he was pressing. It was like watching a marathon runner, spent from having endured the 26-mile ordeal, struggle to finish the last 385 yards. Everyone wants the runner to succeed, but only he can do it. If Ichiro is intent on reaching his career goals, it may be similarly excruciating to watch. What is clear is that like Williams, he will not change his approach and he will succeed or fail as an individual.

© 2015 Chris Komai