Time to leave

Those who answered "yes, yes" to the 27th and 28th questions and were recognized as loyal were encouraged to leave the camps early to join the military or to work or study in Midwestern or Eastern towns. To help Nisei students who had been evicted midway through their studies return to college, the Quaker American Friends Service Committee backed the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, which quickly got to work, helping to send more than 4,000 students to more than 6,000 colleges outside of the military-restricted zones. Quakers also set up hostels to provide temporary accommodation for Japanese people in new cities. It was time for Yoshiko Uchida of Topaz, and Louise Tsuboi and Shiro Kashino of Minidoka to leave.

Yoshiko Uchida ——— Spring

I wrote dozens of letters to the National Council on Japanese American Student Relocation (whose staff already seemed like friends) and filled out countless forms, determined that even if the scholarship to Smith College didn't materialize, I would still go somewhere . My sister, too, was filling out countless applications, hoping to find an opening in her field.1

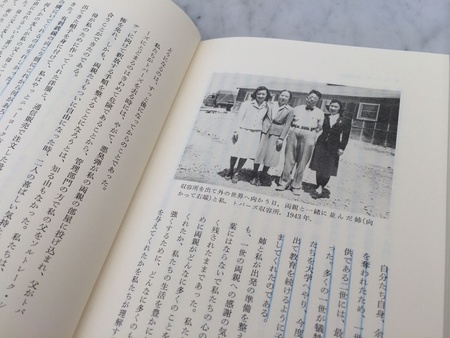

First, Yoshiko's older sister Keiko received a notice that they wanted her to work as an assistant teacher at a nursery school run by the Department of Education at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. Soon after, Yoshiko also received an acceptance letter with a scholarship from Smith College in Massachusetts. On May 24, they received the long-awaited release letter from the Relocation Bureau, and the two said goodbye to their long life in the camp.

For my sister and I, the cold, dark winter was over, and now, at last, spring was in our grasp. Our long captivity in the wilderness was over. At last, we were on the road back to that world from which we had been cut off for over a year.

Louise Tsuboi ——— Early Summer

Louise had already graduated from high school, so as soon as her mother deemed her loyalty to the United States, she encouraged her to study at a four-year university in Chicago. It was Louise's mother's dream to give her children a good education. Louise was the third of six siblings. Her eldest sister studied piano at the Juilliard School in New York, and her younger brother studied aeronautical engineering in California. Louise was her mother's next goal.

Not only did her mother encourage them to go to Chicago, but she also wanted to ease the anxiety of 17-year-old Louise, who was traveling alone for the first time. When her mother heard at the hospital where she worked that a Nisei nurse and her boyfriend, a young man who wanted to become a doctor, were leaving the internment camp to go to school, she asked them to take Louise with them part of the way. The three boarded a train, spent the night in Kansas City, and then boarded another train to St. Louis. From here, the three went their separate ways. The nurse went to nursing school in St. Louis, the young man went to medical school in Philadelphia, and Louise became independent for the first time in Chicago. Before they left, her mother also remembered to safety pin a check for $2,000 to Louise's underwear; it was probably money from selling the store when they were evicted. This was in June.

At the time, Louise says that rather than feeling happy to have left the barbed wire enclosure, she was more anxious about having to decide on her own where to go to school and where to live in an unfamiliar city. Once she arrived in Chicago, Louise settled in at the American Friends Hostel, run by Quakers, and began looking for a school. Given her parents' current situation and not knowing how long their financial situation would last, she decided to go to a one-year vocational school rather than a four-year university. She first applied to the Gregg School of Stenography, but was rejected because she was Japanese, so she decided on Chicago Commercial College, a small school with one teacher to one student. She says that it was precisely because the school was small that she was able to receive an excellent education. 3

Shiro Casino - Early Autumn

Meanwhile, Louise's boyfriend, Shiloh, was in Minidoka waiting to hear from the Army . He had already enlisted. A few months after Louise left for Chicago, Shiloh received his acceptance letter, and in September he headed to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, for training.

Loyalty issues for children

In the Gila River family, Jean Oishi's brothers Yoshiro and Goro joined the military, while his eldest son, Nimasi, a Kibei Nisei who was born in America and educated in Japan, was arrested as a pro-Japanese hardliner during the Camp Chuo University dispute over loyalty and was transferred to the Poston Internment Camp in Arizona. His sister's husband, also a Kibei Nisei, was arrested along with Nimasi and relocated to the Poston Internment Camp, so his sister Hiroko took her children and moved to Poston with her husband. Hoshiko went to college in Minnesota. Jean says:

I was generally aware of the political debates that were raging in the camp, but I didn't get involved. Like all children, I was aware of the debates that older brothers and sisters were having about the war, the internment camps, and the government's attitude toward Japanese Americans.

To me, the loyalty issue was like a disease that attacked my family and gradually reduced their numbers.... My family was torn apart, and you could almost say it fell apart. In any case, the underlying issue was loyalty, but for a long time I treated the cause and effect separately, avoiding linking them. I didn't want to get too involved. 5

Notes:

1. Yoshiko Uchida, translated by Kazuo Hatano, "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of a Japanese-American Family During the War," Iwanami Shoten, 1985

2. See above, "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of Japanese-American Families During Wartime."

3. Louise Tsuboi Kashino, interviewed by Yuri Brockett, Jenny Hones and Hitomi Takagi, August 22, 2013 at Bellevue, Washington.

Louise's father, Kakichi Tsuboi, was from Shodoshima. Tsuboi Sakae, the author of "Twenty-Four Eyes," is her aunt. Since childhood, she dreamed of living in America, and planned to go to America as a sailor and jump off the ship there. The first time, she failed, but the second time, under cover of darkness, she managed to climb a rope from the ship, slid into the cold February sea, and swam ashore in Seattle. This was in 1913. After that, she worked in various jobs, and five years later she returned to Japan to find a wife. Tamie, whom she married through an introduction from her uncle, was also from Shodoshima. She entered the United States legally at this time. After much hardship, the couple managed to run two grocery stores in Seattle before being evicted.

4. Louise Tsuboi Kashino, interviewed by Yuri Brockett, Jenny Hones and Hitomi Takagi, August 22, 2013 at Bellevue, Washington.

5. See above, "Torn Identity: The Life of a Japanese Journalist"

*Reprinted from the 136th issue (February 2014) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2014 Yuri Brockett