The World War II exclusion and detention experience of Japanese Americans is now fairly widely familiar, at least in general terms, to many within the United States. Their knowledge of this particular subject has been broadened and deepened progressively since the 1970s through a veritable media avalanche of historical representations served up by writers, filmmakers, dramatists, artists, oral historians, bloggers, and many others. However, it is quite apparent that this development has not occurred―even for Japanese Americans―with respect to the parallel yet somewhat different (and arguably more dire) WWII wartime experience of Canadians of Japanese descent.

When compared to the abundant documentation of the Japanese American wartime story, accounts of the Japanese Canadian counterpart saga are decidedly scarce. Nonetheless, since the 1976 baseline publication of The Enemy that Never Was by Canadian Nisei (second-generation) journalist-historian and wartime detainee Ken Adachi, there has been a steady stream of notable creative work on this topic. Adachi’s “definitive” book was followed by a riveting oral history volume, Years of Sorrow, Years of Shame (1977), compiled by another Canadian journalist-historian, Barry Broadfoot. Then, in 1981, there appeared Nisei teacher Joy Kogawa’s classic historical novel, Obasan, which she related from her Japanese Canadian perspective as a childhood victim. Next in line were two stirring Sansei (third-generation)-authored books by activists in the Japanese Canadian postwar movement for redress and reparations: Bittersweet Passage (1992) by environmental lawyer Maryka Omatsu, who was born a few years after her community’s eviction and confinement; and Redress (2005) by poet-editor-writer-teacher Roy Miki, who was born six months after his family had been uprooted and imprisoned. More recently there have been a pair of commanding books, both of which are approached from an enlarged North American comparative standpoint, by historians at two Canadian universities: Stephanie Bangarth’s Voices Raised in Protest (2008) and Greg Robinson’s A Tragedy of Democracy (2009). In 2010, one of the most moving interpretations of the Japanese Canadians’ social catastrophe was showcased within the documentary film Force of Nature, a cinematic homage to the eventful life of the Canadian Sansei academic, science broadcaster, and environmental activist David Suzuki.

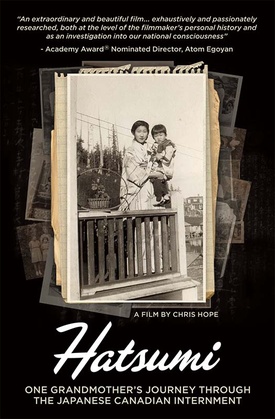

Americans (and also Canadians and others) unfamiliar with the above seminal productions would be especially well served by watching Hatsumi in advance of tackling any one or all of them. This engagingly hour-long educational documentary, rendered in living color and punctuated by particularly apt musical selections, is produced, directed, and narrated by the youthful Toronto-based filmmaker Chris Hope, an entertainment lawyer who is a Yonsei (fourth-generation) Hapa (half-Japanese) Canadian. Entirely family and community funded, Hatsumi was 11 years in the making before its ultimate release by Alliance Films in 2012.

The film revolves around Hope’s persistent and persuasive efforts to get his 80-year-old maternal grandmother, Nancy Hatsumi Okura, a recovering stroke victim, to both confront and convey to posterity her and her family’s traumatic wartime odyssey of removal and incarceration. Together they embark on a strategic intergenerational journey of discovery involving oral history interviews, a true treasure trove of historical photos and home movies generated chiefly by Hatsumi’s late husband, Ken Okura, and, most dramatically, visitations to prewar, wartime, and postwar sites throughout Canada (and even one in Japan) intimately associated with Nancy’s family members. In the process of enacting this journey, the larger WWII story of Japanese Canadians is not only invoked and explained, but also palpably illuminated.

Notwithstanding its tragic subject matter, Hatsumi is negotiated in a pervasively “upbeat” spirit. This is altogether appropriate for a film that simultaneously assays the ravages of racism while promoting social, cultural, and psychological healing.

*This article was originally published on Nichi Bei Weekly.

© 2015 Arthur A. Hansen / Nichi Bei Weekly