2. 1944

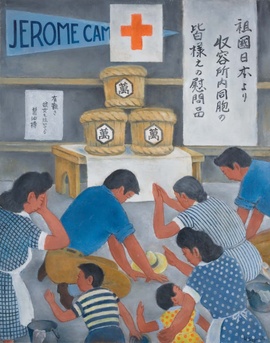

Comfort goods arrive from Japan on an exchange ship — Early spring

(Illustration by Henry Sugimoto, owned by Wakayama City Library)

The scent of home arrived on a ship that exchanged prisoners between Japan and the United States. Supplies procured with funds raised in Japan to help Japanese nationals residing in enemy countries arrived via the Red Cross. 1 The first exchange ship brought green tea, while the second ship brought green tea, miso paste, soy sauce, medicine, entertainment items, and books. From the diary of Tomika Yoshitake, a former teacher at the Japanese language school in Seattle who was in the Minidoka camp:

February 1st

Twenty degrees [minus 6 degrees Celsius]. Clear skies. The snow has melted and the roads are very bad. But it's warm, like spring. During the day, the temperature exceeded 70 degrees [21 degrees Celsius]. At night, as a consolation gift from Japan, we were given a distribution of Kikkoman (440 barrels in this area), and each person was given a pint [about 2 cups], so we received one gallon and one pint [about 4 liters]. Even now, I feel deeply grateful for my homeland. The homeland is now facing an emergency situation where it is unmanned, and supplies are probably in infinite need, but the fact that they thought of us, sent us so many goods from afar, and received them directly is something I can't thank them enough for. I bow three times and bow nine times. 2

The March 25th edition of the Heart Mountain Sentinel lists the names of familiar drugs, including "16 boxes of Ohta's Isan, 199 bottles of Takadiastase, and 102 bottles of Mercurychrome." In an April 1st edition of the Heart Mountain Sentinel under the headline "Comfort Goods Arrive from Japan for Koreans in the U.S.", it also states, "The entertainment items were three shogi boards, seven sets of shogi pieces, four go boards, seven sets of go stones, and musical instruments were five shakuhachi flutes, two ming flutes, and one harmonica." It also states that all the books were censored and included literary works such as "Popular Literature Collection 4, Masaki Fuyooka Collection," "Uno Koji Collection," "The Tale of Genji," "New Japanese Literature Collection Volume 9," "Tannisho," "Salvation of the Cross," and other cultural and scientific books, including biographies of great people and Western etiquette, totaling several hundred books. 3 It is likely that each volume of the Literature Collection was sent to a different camp. Another thing that made me happy was the arrival of the Red Cross Letters from my dear hometown on an exchange ship. Naomichi Kodaira of Minidoka, who received a letter from his mother, wrote the following:

...What made me happiest was a lively postcard written in my mother's pure Zuzu dialect. "Nao-chan, how are you? This summer is so great," she wrote, which made me very happy. My mother's Zuzu dialect is wonderful. When I read it, I can hear my mother's warm voice and see her face. And there was a Chinese poem written on it: "The evening of August 14th was a beautiful moonlit night. The moon shines brilliantly on the ocean. My mother silently thinks of her children from a foreign land. Oh, who can help my old mother commit suicide? I can only pray to the Emperor of Heaven for you to be sincere." 4

When war breaks out, diplomatic channels between warring nations cease to function. We will never forget the work of the International Red Cross, Red Cross societies in various countries, and neutral nations who stood by those who suffered without ever coming into the public eye. In the United States, at the request of the Japanese government, the Spanish consul in the United States frequently visited each of the internment camps to listen to the stories of Japanese people and negotiate with the authorities.

Henry's Choice

"Democracy in America - what it means to me" is the assignment for Henry Miyatake, a sophomore at Hunt High School in Minidoka, for his final report in his civics class. In civics class, students learn about the Constitution and the structure of the U.S. government. Still remembering the talk he heard in his first year by Gordon Hirabayashi ( Chapter 3 of this series ), Henry carefully read the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights, which protects basic human rights, collected materials, and wrote his report.

I wrote 13 pages about the frustrations of being put in the camps and the things that were happening to us that I thought were crazy in comparison to the Bill of Rights. Yes, I wrote about the fraudulent Truman report ( Chapter 3 of this series ) and about the treatment of blacks in the South .

Henry says this, but he is called in by his civics teacher, Miss Amman, and told that he won't be able to pass the exam unless he rewrites it. To make matters worse, the school administration, frustrated by the students' lack of motivation to study seriously at the time, had made a strange rule that if a student failed one class, they would fail all classes for that semester, and the students were campaigning to change this rule. If Henry hadn't failed this class, he would have gotten all the credits he needed to graduate, but he was adamant that he wouldn't rewrite it.

Shiro and the 442nd Regiment - From Spring to Autumn

In May, Shiro-Kasino was sent to the European front as a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a unit made up entirely of second-generation Japanese-Americans. In Italy, he joined the 100th Infantry Battalion, a unit made up of second-generation Japanese-Americans from Hawaii, and first fought against the German and Italian armies on the Italian front, then in September, he went to France. In October, he captured the town of Briella, which was surrounded by German forces in the mountainous Alsace region in eastern France. Since the area was mountainous and forested, tanks and support from the air could not be used, and the soldiers fought on foot, with fierce battles repeated. It was a difficult battle, with many killed and wounded.

Even after the liberation of Briela, the Japanese regiment continued to attack the east side of the town, and on October 24th, the Texas Battalion was surrounded and isolated by German forces in the Vosges Forest. A fellow Texan regiment attempted to rescue them but failed, and on the 25th, President Roosevelt personally ordered the 442nd to rescue the "Lost Texas Battalion." Without any adequate rest, they fought again for four days in the harsh forested mountain region, with the motto "fight for your life," and finally rescued the Texas Battalion. However, in order to save the 212 Texan soldiers, the Japanese regiment suffered 216 deaths and 600 wounded. 6

During this time, letters were the only thing that connected Louise and Shiro. Louise wrote to Shiro almost every day to cheer him up, but the occasional letters from Shiro never mentioned anything about the front, and Louise says that Shiro must have been careful about what he wrote, as there was nothing censored. Shiro was wounded six times on the Italian and French fronts, but when he was in the hospital, Louise knew right away that he had received letters on Red Cross letterhead. Even at times like these, Shiro would cheerfully tell her, "Oh, I was hit by a bullet so I'm taking a break. I'll be back at the front soon."

The two first met when Jim Aktz started a tray service at the Puyallup temporary detention center ( Chapter 2 of this series ), where Louise, a volunteer, delivered a meal to Shiloh, who had just had surgery on his toe.

Searching for work in an unknown place --- late autumn

Billy lived in a small barracks with his mother and father in Heart Mountain. His mother's family, the Itaya family, lived just two doors down from him in the same barracks, so Billy was loved by everyone. There are many photos of Billy with the Itaya family. Comparing these photos, it seems that it was Uncle Sammy who gave Billy ice skating lessons, but by the fall of 1943, Uncle Sammy had also been drafted, and Aunt Eunice, who had turned 18, had left the camp to find work in Chicago. Only Billy's mother Mary remained with the Itaya parents, Junzo and Rio. Billy's father, Bill Manbo, also left his wife and children and went to Cleveland to look for work. In November, Junzo, thinking that they would soon be alone, went to an interview with Seabrook, a frozen food company in New Jersey. Seabrook had been actively hiring Issei and Nisei from the camps to alleviate the labor shortage since the war. With the employment notice, Junzo returned to Heart Mountain to pick up Rio, but during Junzo's absence, Rio had a nervous breakdown due to intense mental stress and needed long - term treatment. Junzo decided to stay by Rio's side and contacted Seabrook to decline the job offer.

Boy's Winter

Children seem to have a mysterious power. They also seem to enjoy toilets and showers that have no partitions. This is Bacon's report from his third winter.

In the men's bathroom, the bowls were less than two feet apart and there was no partition. Sometimes we would sit next to each other and discuss what we were going to do that day. In the open-air showers, we would take one wet towel and throw the other at our naked friends, competing to see who could sting the most. Once, we got some toilet paper and rolled it up like a cigarette, but it tasted awful, so we never did it again. It would have been much better if we'd had someone steal some of their dad's pipe tobacco and rolled it for us. It was a pain to run to the bathroom in the middle of the freezing cold, snowy night, but unlike most other houses, we didn't have a potty. People who did use one could tell right away because they covered it with a cloth and scurried to the bathroom early in the morning. On snowy days, yellow dots would appear on the snow. 9

West Coast eviction orders soon to be lifted

On December 17, the U.S. War Department announced that the evacuation order on the West Coast would be lifted starting January 2 of the following year. This meant that people could return to their homes on the West Coast before they were evicted. The next day, Relocation Administration Director Meyer ordered that all internment camps be closed by the end of 1945.

Notes:

1. With the help of neutral Switzerland, Japan and the United States sent two exchange ships for prisoner exchanges. The first exchange took place in July 1942, when the Japanese Asama Maru and Conte Verde exchanged passengers and cargo with the American Gripsholm at the port of Lourenço Marques in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique). At that time, about 1,500 people returned to Japan, including ambassadors to the United States Nomura and Kurusu, trading company employees, bank employees and their families, researchers and students such as Tsuru Shigeto, Tsurumi Shunsuke, and Tsurumi Kazuko, and people repatriated from Central and South America. The second exchange took place in the fall of 1943, when the Japanese Toa Maru and the American Gripsholm exchanged about 1,500 prisoners and supplies in Goa, India, which was then Portuguese territory. As part of this exchange, the Gripsholm returned to the United States on December 1st with tea, miso paste, soy sauce, musical instruments, medicines, comfort books, as well as nostalgic letters from relatives and acquaintances in Japan, totaling approximately 15,000 "Red Cross Correspondence."

Takashi Masui, "Records of International Humanitarian Activities during the Pacific War (Revised Edition)," Japanese Red Cross Society, 1994

Shunsuke Tsurumi, Norihiro Kato, and Hajime Kurokawa, "Japan-US Exchange Ships," Shinchosha, 2006

"Happily Receiving the Comfort Goods" by Teruko Kumei - A Chain of Gratitude Linking the Relief Goods from Wartime Exchange Ships to the LARA Goods, Overseas Migration Museum

2. Kazuo Ito, "80 Years of American Spring and Autumn," Seattle Japanese Association, 1982

3. Heart Mountain Sentinel, Vol. III No. 13, March 25, 1944.

Heart Mountain Sentinel, Vol. III No. 14, April 1, 1944.

4. Naomichi Kodaira, "American Internment Camps: War and Japanese Americans," Tamagawa University Press, 1980

5. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, May 4, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

6. The Nisei who enlisted in the Army not only served on the European front, but also received training in the U.S. Military Intelligence Service and, using their language skills, worked on the Pacific front and in postwar Japan.

7. Louise Tsuboi Kashino, interviewed by Yuri Brockett, Jenny Hones and Hitomi Takagi, August 22, 2013 at Bellevue, Washington.

8. See Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II.

9. See Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II.

*Reprinted from the 136th issue (February 2014) of “Children and Books,” a quarterly magazine published by the Children’s Library Association.

© 2014 Yuri Brockett