Children's daily life—Summer

By the time they reached high school age, there were many organized pastimes, such as baseball, basketball, and dance parties, but organized activities for preteens were limited, and they often hung around the camp in groups and caused trouble. So the administration introduced Boy Scout and Girl Scout activities, and gathered boys together to form a tackle football team. Here is a look at the daily life of children from a report by 13-year-old Bacon, who spent his childhood at Heart Mountain Camp:

Soon we were allowed outside the barbed wire fence, so long as we stayed within the camp grounds, and could hike into the nearby hills to look for squirrels, toads, and rabbits. ... On hot days, after playing outside all day, we sometimes stopped by the concession stand for a five-cent, single -layer ice cream cone.

A Nisei man, much older than us, also took an interest in our group of boys and taught us how to make gliders out of balsa wood. We competed to see whose glider could fly the longest, and he taught us how to attach a propeller to a glider, how to wind a rubber band to make a motor that would fly for a short time when we let go. One day, he suggested that we go to a nearby town so that we would remember what normal life was like. With permission, we went by bus to a town called Powell, 12 miles away. The only thing I remember clearly about Powell was a "No Japanese" sign in a store window. I was almost 14 years old, but it was my first time and I was really scared.

We once slept by a nearby river with some boys who lived on our block. We went to the dining hall, asked for a sausage and a loaf of bread, slipped out through a nearby fence where there were no guards, went through a culvert six feet in diameter under the highway, went through a deep ravine that led to the Shoshone River, and made a tent out of the blankets we had brought with us. There was a watermelon patch nearby, but unfortunately we had no idea which ones were ripe, so one of the boys dug his pocket knife into them and began to check for ripeness. The first ones were not yet sweet, so he cut one open, one after the other, until he found one that was sweet. ...Soon after, the weekly camp paper carried an article about the destruction of the camp's watermelon patch. I am now deeply ashamed that I played a part in that episode, truly. 2

Dreaming, reading books--- midsummer

It seems that the children knew that dreaming and reading books would help them jump over the barbed wire fences. Ms. Breed continued to send them books even after they were transferred to the Poston Internment Camp. This is a letter from Margaret Ishino dated August 4th.

Dear Mr. Breed,

Sometimes I wish I were Webster or Winston, so I could say more than "thank you" to you for all the beautiful books you send me, but I'm glad I'm just Margaret Ishino, because you give me so many wonderful books.

When peace returns to the world, I would like to travel to three countries. First of all, I would like to go to Alaska, the "Land of the Midnight Sun," to see the Eskimos and their igloos [dome-shaped homes made of snow and ice]. I would also like to see the salmon swimming upstream. Reading "Child of the Sea of Mist" has made me want to go even more.

Secondly, I want to see France. I don't know why, but I feel an affinity with France. I've always wanted to learn French. In our class, each student chose a country to write their term paper on. I've always thought that I can't die until I've seen Paris, so I chose France.

Lastly, Japan. I want to see the water lilies and little fishes swaying in the stream behind my aunt's house. Japan has four seasons, spring, summer, fall, and winter, each different and picturesque. Then I want to spend the rest of my days peacefully in America, my sweet home.

Thank you again. …May God bless you abundantly.

Margaret Ishino 3

Next, we see how Elizabeth Kikuchi spent her summers in Poston. Her father was a pastor, and before they were evicted, she lived in the parsonage or the church, and didn't have her own home. Breed sent her a book called "A Home for Elizabeth." Breed's father was also a pastor, so he must have understood Elizabeth's desire to have her own home someday. He chose books for each of his children.

We were children who dreamed. We would get up at four or five in the morning. We would walk three to five miles to the river before the sun got too hot, spend the whole morning and afternoon there, and come back in the evening when it was cooler. We often drew pictures while we were there. We were teenage girls, and we imagined life after the camp in a college dormitory or in our own homes. We would draw room layouts in the sand, saying, "My bed will be here, and here will be my bedside table," and we would imagine a better life beyond the barracks. I remember when Ms. Breed sent me the book, A Home for Elizabeth, I said to my mother, "We've never lived in a home of our own." I'd lived in a parsonage, a church, a stable, and a barracks. So when Ms. Breed gave me this book, it was special. I felt that she was sending me a book about my real home. She must have been very thoughtful about the books she sent to each of us. 4

Poetry

The barracks Jean and her family lived in at the Gila River camp were on the edge of the camp, with the block just behind them used as storage. One day, Jean and her friends found a pile of books in one of the barracks and crept in through a window.

… There were piles of old textbooks and other things donated by various outside organizations. … I rummaged through the piles of books at random. Most of the books were Dick and Jane type textbooks and not particularly interesting, and the only one I found was the "Masterpieces of Poetry." I showed the books I brought back to my room to Goro, who was delighted. We read many poems together. My brother's favorite was Edgar Allan Poe's "Annabel Lee," which he recited with great emotion. I then took over to recite, and he was as moved as when I pretended to play the violin. We also read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Village Blacksmith" and Walt Whitman's "O Captain, My Captain." I loved these three poems, and I read them over and over again even after my brother passed away. These poems seemed to be calling out to me from afar. 5

Jean, who later majored in literature at university, said, "I read a lot of poetry, but I never felt the same intimacy that I felt from the book that my brother and I stole in Gila." Perhaps the higher the barbed wire fence, the more restrictions there are, the more deeply a poem you encounter there resonates with you.

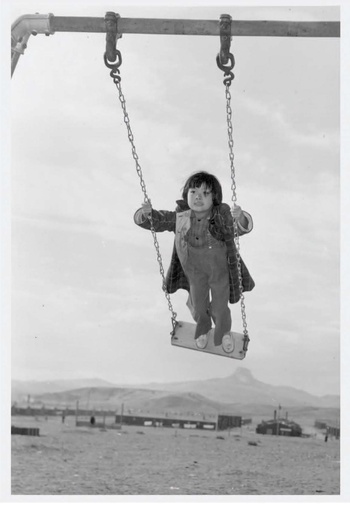

Girl on a Swing — Late Autumn

With the desolate Heart Mountain barracks in the background, the girl swinging alone seems to smile a little reflexively as the camera is pointed at her, but before the photographer interrupted her, she was probably swinging intently and lost in thought. What was she thinking? What was she looking at as she gazed into the distance? The photo was taken on November 24th by Hikaru Iwasaki6 , who later became the only Nisei to be officially appointed photographer for the Relocation Bureau.

Notes:

1. A hemispherical ice cream scoop with a handle used to place a scoop of ice cream on a cone.

2. See Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II.

3. Joanne Oppenheim, translated by Ryo Imamura, "Dear Breed" Kashiwa Shobo, 2008

4. "Dear Breed" (see above)

5. See above, "Torn Identity: The Life of a Japanese-American Journalist"

Jean describes how she felt at that moment:

Rereading them today, I see that the reason I was attracted to these three poems is because they sing of lost love, the death of a father, and a life of disappointment, and that I resonated with this sense of despair. Whitman's poem was the most difficult to understand, but also the most exciting. The protagonist of the poem, "my captain," who is also "my father," lies on the deck of the ship and "grew cold and died" after completing his mission in an expedition full of hardships. I felt sorrow for the tragic protagonist, but somewhere in the back of my mind I found a sense of peace. I became a little worried that the poem's sense of relief meant that I wanted my father to die.

6. From 1944 to 1945, Iwasaki worked as a photographer for the Relocation Bureau, visiting people who had left the camps and were starting new lives, taking photographs and providing detailed captions. He hoped that his photographs of people who had left the camps early and were working energetically in new places would provide some encouragement to those who were hesitant to leave the camps.

*Reprinted from the 136th issue (February 2014) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2014 Yuri Brockett