Read Chapter 3 (3) >>

Helping with the harvest — late autumn

It is also a fruitful autumn. It is harvest season, but farms in California, Arizona, Idaho, and Wyoming are suffering from a labor shortage. The people who used to help with the harvest have been drafted into the military or moved to cities that are booming with the military demand, so there is no one left. The governor, who is in a difficult position, appeals to his local senator and the War Relocation Administration to have Japanese-American prisoners help with the harvest as a "patriot's duty." Many high school students apply, as it is a chance to get out of their cages, and Breed's daughter Louise goes out to pick cotton with her classmates to "raise funds for the school newspaper." This is a postcard that Ben sent to Dr. Wills in Seattle from Twin Holes, Idaho, where the farm is located.

November 12, 1942

Dear Dr Wills,

I am done with work in the sugar beet fields and in two days I will be back at my new address. I have been out of camp so long that I must get used to camp life all over again. The enclosed paper tells me that they are now erecting a barbed wire fence at Minidoka with eight guard towers. I thought I left all these inconveniences behind when I left Camp Harmony at Puyallup. It seems my old life is my new life again. I just can't understand why the government needs to fence us in when they just threw us in an area with nothing but sagebrush in every direction.

If this is democracy, then I prefer a strict dictatorship, so at least I'm not forced behind a barbed wire fence.

As always, Ben 1

Mrs. Pollack - Late Autumn

The new school year finally began on November 14th, the day Ben returned to Minidoka Hunt High School. Henry Miyatake, now a first-year high school student, said of the teachers in the camp, "There were all kinds of teachers, from mediocre teachers who had lost interest in teaching, like the teachers who had been teaching children on Indian reservations for a long time, to teachers who were passionate about their mission. Fortunately, my teacher in my first year of high school, Mrs. Pollack, was the latter."

...The teacher felt that some injustice had been done to the people in the camps, and wanted to do what he could for the inmates, and with very noble intentions, he wanted to somehow rectify that injustice. Her husband was away from home serving in the Marines, so he wanted to use his free time for the Japanese people in the camps, and also to do something constructive that would add to his career, so he became a teacher at the camp.

He was a very dedicated, talented and intelligent teacher. He had a good grasp of the situation in the camp and made a good judgment about what was going on. He noticed that we had little motivation to study and that we were no longer making an effort to become good students. He told us, "This is a temporary situation. In two or three years, you will leave this camp and return to your home town to receive a normal education. For that reason, you must continue studying now."

It seemed that our teacher was motivated not just to teach us, but to prepare us to take another step in our education. One of the projects he gave us was to freely imagine our future environment. This would make us think of this camp life as temporary and to think about what kind of career we wanted to have in the future, what kind of job we wanted to have. It was a first for me to think like this. It was different from my parents' and from anyone I had ever met. ... We were also given an interesting assignment: "What university do you want to go to?" He brought out a huge number of university catalogs and lined them up on his desk and on his bookshelf so that we could freely pick them up. I had never heard of Miami University before, but there were catalogs for Miami University and Harvard University as well. ... 2

There was also this incident. One day, Mrs. Pollack heard from somewhere that Gordon Hirabayashi was in Minidoka, and asked Henry, who was the class representative, to come and speak to the class. Gordon Hirabayashi was a student at the University of Washington at the time, but he deliberately broke the night-time curfew for Japanese Americans, disobeyed the internment order, voluntarily turned himself in to the FBI, and was incarcerated. He was one of those who acted on his beliefs, claiming that the government's treatment of Japanese Americans "violated human dignity and denied the right to life." 3

Most of the class knew nothing about him, nothing at all about what he had done or what he was planning to do. But a man who would later become a legendary figure in the history of the American Constitution spoke to us directly. Gordon Hirabayashi's lecture left a deep impression on the class. I, too. Gordon's story burned into my mind. 4

Afternoon Tea in the Library — Winter

From the Topaz Times, published on December 2, 1942. A library with tea service must have been a very relaxing space. It has also been reported that rumors and gossip have decreased since libraries were established.

The Community Library was officially opened at Recreation Hall 16. The library, which has a fairly extensive collection of books, was delighted with an afternoon tea service provided by the librarians led by Director Nobuo Kitagaki. 5

Manzanar Riots , Santa Claus , and Don't Put an Apple in a Lemon Box - Winter

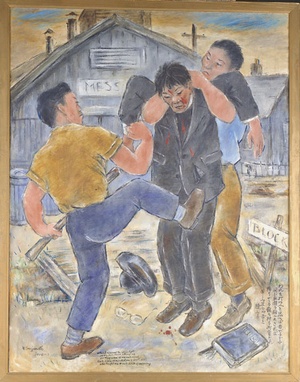

On the night of December 5th, Fred Tayama, a second-generation American who had just returned from a JACL meeting in Salt Lake City, was attacked and beaten. Tayama testified that one of the six rioters was Harry Ueno, a second-generation American from Terminal Island who worked in the kitchen. Ueno was captured and detained for questioning at the nearby Independence prison. Ueno had always warned that a camp warden was stealing meat and sugar from the food store and selling it on the black market, so people immediately demanded his release, thinking that Ueno's arrest was a plot to bury his warning. More and more people gathered, and throwing tear gas was ineffective. Eventually, the situation escalated, with people throwing stones and driving an empty car towards the police officers. Sensing danger, the police officers opened fire, killing 17-year-old James Ito, who happened to be there, on the spot. Another person later died from the wounds he received. Nine others were injured. This is the Manzanar riots.

On the evening of the second day, exactly one year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Mary Matsuda heard the news of the Manzanar riots from her brother Yoneichi. She was shocked and frightened. "Something is wrong somewhere. Will there be riots here too? What will the government do? What will happen to us?" Mary later explained the cause of the riots as follows.

Different forces clashed. One was the anxiety caused by the brutal evictions, forced confinement, poor conditions, lack of meaningful work, and other problems within the camp. One can only imagine how the people of Terminal Island, who suffered particularly badly, felt. There were angry people from Terminal Island at Manzanar. The other was the presence of the pro-American Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). There were rumors that the JACL was secretly passing on the names of "troublemakers" in the camp to authorities, which made other detainees very angry. 6

The Manzanar Riots were the result of a sudden explosion of magma that had been bubbling up deep beneath the surface. Immediately after the riot, martial law was imposed on Manzanar, and the schools, post office, and everything else were closed. An oppressive atmosphere enveloped the camp. The people who worked at the administration office were also evacuated, but one teacher insisted on staying. What did Miss Eli see?

There was no mail delivery, so just before Christmas the post office was swollen with letters and packages to deliver. Then a miracle happened. Herbert Nicholson, a Quaker, was in a really good mood and came bearing a load of toys that had been donated by the people. There was a fairly large fire break between the barracks, and he parked his truck in the middle of it and started handing out toys from the truck. Suddenly the mood of the whole camp changed.

Meanwhile, Walt and Millie Woodward from Bainbridge Island had repeatedly tried to contact Manzanar, which was under martial law, but their messages were not received, and it was some time before the safety of the islanders was finally confirmed. Walt immediately sent a strongly worded letter to the War Relocation Administration, saying, "It is wrong to put the gentle Bainbridge Islanders among the violent Californians. It is like putting apples in a lemon box. The Bainbridge Islanders should be moved to Minidoka, where their fellow Seattle natives live." 8

Notes:

1. Letter dated November 12, 1942. Elizabeth Bayley Willis Papers. Acc. No. 2583-6, Box 1. University of Washington Libraries Special Collection.

2. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, May 4, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

3. In addition to Hirabayashi, other well-known individuals who acted on their beliefs included Fred Korematsu, who protested the injustice of forced detention, and Minoru (Min) Yasui, who questioned the constitutionality of the curfew. Mitsue Endo also appealed to the court from the Tule Lake detention center, objecting to his detention.

4. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, May 4, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

5. Topaz Times News Daily, Vol. I No. 27, December 2, 1942.

6. Gruenewald, Mary Matsuda. Looking Like the Enemy ——— My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese-American Internment Camps, Troutdale: NewSage Press, 2005.

7. Seigel, Shizue. In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment . San Mateo: AACP. Inc., 2006.

Herbert Nicholson, whose name sounds like Santa Claus, was born in 1892 and was a Quaker. After more than 25 years of missionary work in Japan, he returned to the United States in 1940. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he visited each prison for the more than 3,000 Japanese Americans who were detained in the Department of Justice prisons, and, using his fluent Japanese, he helped them with their trials and worked hard to ensure that the detainees could return to their families as soon as possible. He also ran errands for Japanese Americans in internment camps, helped them with any unfinished business, and even rented a truck to deliver a ton of discarded books from libraries in Los Angeles to Manzanar.

8. In February 1943, 177 Bainbridge Islanders arrived at Minidoka.

*Reprinted from the 135th issue (October 2013) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett