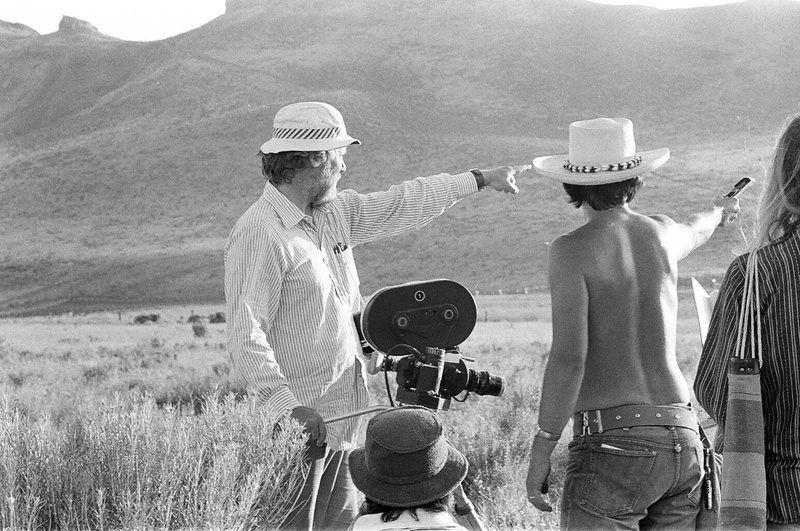

Several people who worked on filming Farewell to Manzanar at the Tule Lake location spoke about it for this article, beginning in a lunch conversation in 2012 with Korty, as the film’s director, and Lope Yap, Jr., who served as unit manager and location manager.

Korty, who is based in Marin County, was then working on a documentary, Peaches by Masumoto, about organic peach farmer and author David Mas Masumoto, a member of the National Council on the Arts. Yap had built a career as a successful producer and special effects designer in films including Titanic and The Hunt for Red October.

At the time of the film’s re-release in 2011 and 2012, Korty and some of the actors gave interviews about the events invoked and conversations begun on the set. Many interviews have focused on artistic and personal aspects of re-enacting the Manzanar incarceration experience. The fact that filming took place mainly at the Tule Lake site added an extra layer of resonance.

The Wild West

“Tule Lake, I have to tell you—It was really a wild…Wild West out there when I was there,” said Yap. “I imagine not much has changed.”

The authors of the original Farewell to Manzanar book have suggested the same: in an essay recalling the filming, they commented, “The Last Picture Show could have been filmed at Tule Lake, or The Misfits, or A Fistful of Dollars.” (The essay, titled, “Another Kind of Western,” appears in James Houston’s 2008 memoir, Where Light Takes Its Color From the Sea, and is cowritten with Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston.)

Among the film’s staff, Yap saw the most of the place because he unexpectedly became the advance man and local liaison for the production. He said, “I was going to Tule Lake for the weekend to drop some equipment off.” People had questions about the production. He called them in to his boss, who said, “Well, why don’t you go answer them?” Yap recalled: “I said, OK. I never left. A weekend became three and a half months, marooned.” He had his clothing sent to him piecemeal: “Oh, I’ll be here another week, send up another shirt or two.”

His production tasks included rounding up period artifacts, from a washing machine to a bus. “It was like a scavenger hunt. It was crazy, it was nutty, it was actually enjoyable.”

“I learned a lot from Tule Lake,” he said. “It’s a big chapter in my 40-some-odd years in the business.”

Korty remembered arriving to see an alarming banner over a street saying, “Unload Your Guns.” It was addressed to duck hunters. Tule Lake is still a duck-hunting destination. Its high school team is still called the “Honkers.” But in the middle 20th century, even into the 1970s, duck hunting had a lot more to do with the town’s identity and livelihood than it does now. Yap remembered homemade signs in every shop window offering taxidermy services for hunters.

Both recalled the towns of Newell and nearby Tulelake as remote, the motel furniture rickety, the population either stuck in place or living elsewhere and returning only for family visits. Yap, then in his mid-twenties and engaged to be married, said he had to fend off endless offers of weekend dinners and introductions to local women: “Any female from eight to 80 years old, with or without teeth, [was] trying to figure out a ticket out of that valley.”

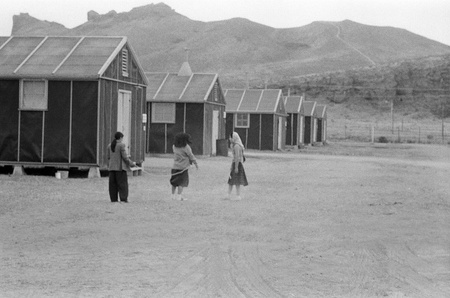

Newell’s most helpful resource for the film was the former military police barracks compound. Isolated from other housing, the MP complex had changed its appearance relatively little since the camp’s closure in 1946. Federal authorities had prepared it briefly in the 1950s to hold “dangerous subversives,” but by the 1970s the property was in private hands. The Fletcher family, who bought it around 1963, had converted the rows of barracks into the Flying Goose Lodges, a subdivision of budget housing and seasonal duck hunters’ cabins.

Under Robert Kinoshita’s guidance, the Flying Goose became Manzanar. It was a matter of returning authentic original MP barracks to something like their original appearance—for example, by tacking on fresh tarpaper—and building guard towers that matched Kinoshita’s memories. (Better known as a designer of Hollywood robots, Kinoshita died in December 2014 at age 100.)

Yap explained, “All the people that we actually inconvenienced in Newell” kept on living there. The set designers redid the ex-barrack houses’ facades to make them barracks again. “We had to relocate all their propane tanks” because the wartime inmates had used small coal stoves for heat. “We had to cover all the blacktop.”

As for the dust, Tule Lake supplied its own.

(The “Flying Goose” later became a rural slum with a reputation for drug trouble. Yap wasn’t surprised to hear it. He said he felt “the heritage of that energy” then. “I just always felt that, if walls could talk, these things could talk well.”)

Yap said filming lasted a total of only 36 days: most of the time at Tule Lake, and only a day or two at the real Manzanar site. The cast and extras spent a day filming the riot scene at Santa Anita Jail in Alameda County. (Kinoshita, who was a small-plane pilot, flew Yap down to Livermore for the day from Klamath Falls.) Some scenes from the Justice Department detention of the central family’s father, Ko Wakatsuki, are probably at Santa Rita Jail in Alameda County, which was also used as a set for the Manzanar riot scene. Other locations were in the San Francisco Bay Area. San Francisco’s Presidio was used for the pivotal interrogation scene where Mr. Wakatsuki reproaches a squeamish but dutiful FBI man. The Wakatsuki family house, in opening scenes before the incarceration, was in Tiburon.

When the production designers moved south from Tule Lake to Manzanar they brought small pieces of the sets to film outdoor scenes against the Sierra backdrop. At one point Yuki Shimoda, as Ko Wakatsuki, stands mourning the death of his soldier son, with his hand on the wire fence, looking up at the Sierra ridges. Yap said, to film that scene at the actual Manzanar site, “all we had was the front of the barracks” plus ten feet of fence. “And it works.”

Yap remembered it as an example of thrifty set design, prepared with future director/producer Drew Takahashi. “Drew and I constructed the corner of the fencing and we brought a part of the security tower to give you that little edge that you and I are really in this environment, but if you pan one inch in either direction, we are in 1975 and there’s nothing here. You just assume there’s hundreds if not thousands of people in this little moment where, you know, Yuki goes to the fence…and there’s [Mt.] Whitney in the background.” Then, he said, the view shifts to a miniature model of the camp, filmed in a small room of John Korty’s office.

In the completed film, while Manzanar is reenacted in the foregrounds, Tule Lake shows through in the outdoor backgrounds, like an underlayer of cloth in a subtly different pattern.

Eyes familiar with the Tule Lake Basin will notice its differences from the Owens Valley: tawny dry grass instead of gray sagebrush; slopes that are nearer, lower, and lumpier than the austere Sierra foothills behind the real Manzanar; black volcanic rimrock at the skylines instead of remote high granite. In a few scenes of arrivals and departures at “Manzanar,” the camera even swings past Tule Lake’s most distinctive landmark, the volcanic crag known as Castle Rock. Korty and Yap said the brief Castle Rock images weren’t intentionally left in.

Hiro Narita, who was the film’s cinematographer, said he tried to keep out the iconic Tule Lake silhouette except in quick moments—“We didn’t want people to recognize it.”

On more than one location

The location choice at Tule Lake was a simple decision based on logistics. Fortuitously, though, it created a way to revisit Tule Lake’s wartime history when that was not easy. Notorious during the war, the Tule Lake “Segregation Center” began with the same status as the other nine large War Relocation Authority camps, but after 1943 became a heightened-security camp within the incarceration system. As a result of the government’s flawed loyalty review process, which based life-changing decisions on responses to confusing questions in an infamous questionnaire, Tule Lake was designated to imprison those households whose adult members were deemed “disloyal”.

As of 1975 it was only just possible to talk publicly about Manzanar, let alone Tule Lake. Because of the location choice, the production contributed not only to the memory of the Manzanar experience, but also to the idea that something important, worth remembering as injustice, had happened at Tule Lake.

Close friendships formed on the set through such moments. Akemi Kikumura Yano, who played the role of Chiyoko in the film, developed a close friendship with Nobu McCarthy, who played the roles of Misa and of the adult Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston. Thinking back, Akemi Kikumura Yano (who is the aunt of this article’s coauthor, Laurie Shigekuni) reflects that their shared experiences working on the film “influenced their future career choices and collaborations.” She notes that Nobu McCarthy later became the Artistic Director of East West Players and produced plays about the camp experience, and she herself undertook a curatorial and leadership position at the Japanese American National Museum “to make known the experiences of Americans of Japanese ancestry as an integral part of our nation’s history.”

Director and writer Momo Yashima has written previously that her conversations with activist Frank Chin about Japanese American draft resisters began on the Manzanar set, where she played the important role of Alice. Chin was a consultant and one of several activist intellectuals who served as extras in the Manzanar production. He later criticized it scathingly in an open letter to Mother Jones as leaving out the issue of white racism, and asked to have his name removed from the credits.

Yap said the Manzanar production was a recurring tie for people who were in it, and became a point of reference in later conversations with actors Seth Sakai and Clyde Kusatsu.

The Tule Lake site had especially traumatic personal meaning for the late actor Yuki Shimoda, who was himself imprisoned throughout the war at Tule Lake. He chose to express his own pain on returning to Tule Lake through his portrayal of Ko Wakatsuki, father of the Wakatsuki family.

Shimoda discussed some of his approach to the 1975 filming with Barbara Parker, who was on the set as production staff while her husband, Hiro Narita, served as cinematographer. Parker, who spoke with us before her own death in 2013, recalled how Shimoda carefully modulated his personal Tule Lake experience to suit the somewhat different Manzanar sensibility, often drawing out extras who had been at Manzanar in casual-seeming conversations “which really were very thorough research of a sort.” He stuck to “what was Manzanarish about people’s lives and personalities…how it affected their behavior and their feelings about themselves and one another.”

Parker said that Shimoda carefully did not go to the site of the camp until it was time for his character to arrive on the bus from prior Justice Department detention in North Dakota. In the arrival scene, Mr. Wakatsuki steps out of the bus, sees the desolate place where he has arrived, and is seen by his family to have aged badly since his arrest. Parker said that, as he had arranged, Shimoda’s portrayal of that moment was informed by his own first sight of the Tule Lake camp since he left it as a newly freed prisoner in the 1940s.

Hiro Narita, the cinematographer, added that Shimoda had not known that the familiar Castle Rock would be in his field of view as he stepped off the bus: “The first thing he saw was this mountain and all of the family members lined up to greet him, and that shock in his expression was real.”

The resulting scene is among the most powerful of the film. Actors have mentioned repeatedly in interviews that the experience of filming it was a time of mourning and bonding for the film’s on-set community; they wept in and out of the shot, and did not stop when the cameras turned off.

Korty said Shimoda told him about his own real first day at the Tule Lake camp, how there was no furniture in the barracks and people needed to build it out of scrap wood. The Army had lots of usable wood but it was in a scrap pile guarded from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. People would “drift down there” to wait for the pile to become unguarded as of 5 p.m. Shimoda’s father was deceased. His mother sent him, at 17, “not a big guy, he was kind of small and lightweight,” to get some wood for a table. When the guards were gone at five there was a big grab, and he had to go home empty-handed. “He said it was one of the worst days in his life.”

Narita, though born and raised in Japan, had a story of his own about a prior disturbing experience at Tule Lake. He had been to Tule Lake once before, in the late 1960s, sent by director Michaelangelo Antonioni to document the location for possible use in the film Zabriskie Point. Antonioni had told him little about the history of the place—only that “something terrible happened there.” It was one of several requests Antonioni made as part of the Zabriskie production for film of painfully evocative American sites. Among other assignments, Narita shot footage in the midst of the Chicago 1968 riots that, unlike the Tule Lake material, was partly included in the film.

Narita found little drama in Newell—just barracks and ruined buildings. He filmed them anyway as documentation for Antonioni’s reference. While he was working, a ten-year-old boy walked up to him. The boy said, “Do you know something?”—“What?”—“The [J-word] used to live here.”

The Klamath Falls Herald and News preserves a warmer local response from columnist Ruth King, who as of the 1975 production was nearing the end of a long career with the paper. During the war, Herald and News coverage of Japanese Americans was almost uniformly hostile according to a 2005 review of the paper’s undigitized wartime editions by historian Mark Clark. But in 1975, King published favorable articles about the film production and its portrayal of Japanese Americans’ incarceration as an injustice. King interviewed Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, who was on the set as a consultant throughout the production, and added a personal memory to the writeup: that meeting the author “brought back memories of another young Japanese American woman, Nancy Yamamoto,” an incarcerated journalism student who had worked for the Newell Star camp paper and “died before she was allowed to return to her former home.”

(King gave an interview in 1973 as part of the CSU-Fullerton oral history series on Tule Lake, saying she was “entirely sympathetic” to incarcerated people she met as a reporter writing about the camp during the war. She told interviewer Sherry Turner that Nancy Yamamoto’s brother Obie was “repatriated” to Japan while her U.S.-born brother Arnold was killed serving in the 442nd in Italy. “Nancy died down there, apparently of a broken heart.”)

© 2015 Martha Bridegam and Laurie Shigekuni