Read Part 1 >>

The fake palace fraud incident also occurred right after the end of the war

When asked about his motivation for moving during an interview (January 10, 2013) in a hotel lobby in São Paulo, he replied, "I heard that Tarama had no successor. I had a lot of connections with Americans, but I thought it would be easier to live in South America than a Protestant country, so I had been wanting to go there for a while."

At that time, there was a big uproar in the Korean community. It was a time when the aftereffects of the war were still strong. In 1954, after Tarama-san had moved, the "Fake Palace Incident" occurred, in which a conman (Takuji Kato) who called himself "Asakanomiya" committed a scam to collect donations, and Kawasaki Sanzo, who called himself a "special agent," caused a big stir.

When asked about the fake prince incident, he laughed and said, "Prince Asakano is my brother-in-law, so I know him well. I could tell right away that it was a lie. It's an impossible world. I had heard that there was a fuss about winning and losing, but I didn't think it had anything to do with me. Those kinds of people have never asked to contact me. If they came to see me, I would have told them, 'You're so stupid,' but I never had the opportunity."

He took over the management of the Tarama farm for about 10 years, after which the farm moved to the city of Sao Paulo and served as auditor for the Produtores Coffee Warehouse Company and vice chairman of the management council for 30 years.

About 10 years after moving to Okinawa, he married his wife, Alysse, the daughter of the wealthy Okinawan Hanashiro Kiyoyasu. She is a quasi-second generation who spent the war in Japan and returned to Brazil after the war. There was a rumor that the Hanashiro family was a descendant of the Ryukyu Dynasty, so I wondered if it was possible, and when I asked Tarama about it, he denied it with a single word: "No, it's not."

Furthermore, thinking that "if I'm going to live in Brazil, I might as well get the right to vote here," she naturalized around 1970. After the war, she quickly renounced her imperial status, emigrated, married an Okinawan, and naturalized, in quick succession, in a series of actions that seemed to make her break with something.

He served as president of the Tokyo Association of Friends of Brazil, vice president of the prefectural federation, vice president of the Japan Cultural Association, and vice president of the Brazilian Association of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. When the World Cities Summit was held in Tokyo in 1985, he attended as a special advisor to then-Mayor Mario Covas, and worked hard to realize the friendship agreement between Tokyo and the Sao Paulo region in 1990. He was always involved in exchanges as a bridge between Japan and Brazil.

In the December 4, 2001 issue of the "Birth of Princess Masako" special issue, Tarama said, "A female emperor would be great." "A female emperor would be great. It would just require a slight change to the constitution. I welcome it," she replied cheerfully. "We've had female emperors in the past. Japanese culture flourished during the era of female emperors. If a queen were born, the Japanese people's consciousness would change. Japan would change, too."

So, am I an immigrant?

When I asked him in 2013 if I could cover him as part of a special feature marking the 60th anniversary of the start of postwar immigration, he didn't get angry, but just looked a little troubled and remained silent. After a short pause, he answered my question, "So, am I an immigrant?", which took me by surprise. For a moment, I could see a glimpse of his upper class consciousness as a former member of the imperial family.

He abandoned his family name from the former Imperial family, emigrated to Brazil earlier than anyone else, married an Okinawan woman, became a Brazilian citizen, and praised the female emperor. As a former member of the Imperial family, he has consistently maintained a radically liberal temperament and enlightened thinking. Where on earth did this attitude come from?

* * * * *

Historically, his grandfather, Prince Kuninomiya Asahikoshinnou (1824-1891), was a leader of the "Kobu Gattai" faction during the turbulent period of the late Edo period. The "Kobu Gattai" faction was a moderate faction that aimed to strengthen the existing shogunate-han system by reorganizing the traditional authority of the Imperial Court (Ko) and the shogunate and various feudal domains (Military).

In the turmoil of the late Edo period, the moderate "pro-shogunate" faction wanted to reform the shogunate and be done with it, while the radical "anti-shogunate" faction rejected the status quo and believed the shogunate must be overthrown rapidly rose to power. The "imperial-shogunate unification faction" was part of the pro-shogunate faction, and ultimately lost control to the anti-shogunate faction. The spearhead of the "anti-shogunate" faction were the Satsuma and Choshu clans, and it was these forces that ultimately gained power and forced the Tokugawa government to return rule to the Emperor, bringing about the Meiji Restoration.

As a result, Prince Kuni Asahiko, although a member of the Imperial family, maintained a distance from the new Meiji government. Therefore, even when Emperor Meiji moved the Imperial Palace to Tokyo, the Kuni family did not move there.

The Wikipedia article "Prince Kuni Asahiko" (accessed April 22, 2015) analyzes, "It has also been pointed out that these circumstances and treatment may have had a complex influence on the feelings and actions of his later sons, including Prince Kuni Kunihiko and Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko (note: Tarama's father)."

The most liberal father in the Imperial family

Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko (note: Tarama's father) married the ninth daughter of Emperor Meiji in 1915, and studied at the Military Academy of Saint-Cyr in France in 1920. "During his time studying abroad, he became accustomed to the free spirit of France, formed friendships with Claude Monet and Clemenceau, and enjoyed driving and living with his local girlfriend. As a result of his time studying abroad, he became known as one of the most liberal thinkers in the Imperial family" (see Wikipedia, "Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko," April 20, 2015).

Perhaps it was because of the influence of his father that Tarama chose a liberal lifestyle and immigrated.

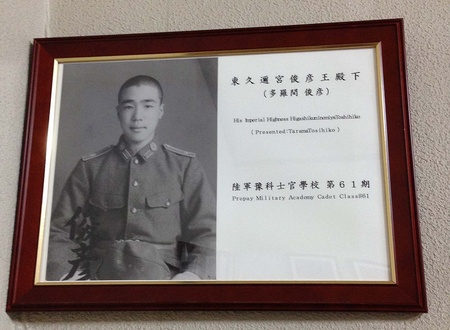

As is customary for members of the imperial family, Tarama studied at Gakushuin before entering the Army Preparatory School. A photo of Tarama, who was 16 years old at the time, is still on display at the Self-Defense Forces base in Tokyo. He graduated from Keio University's Department of Politics.

Three days after the Potsdam Declaration was accepted, my father was appointed as the 43rd Prime Minister (August 17, 1945 - October 9, 1945), the first postwar Prime Minister. Even though Japan had surrendered, the army and navy were still deployed both inside and outside Japan, and the most important task that GHQ required of this Cabinet was the disarmament of the Japanese military. At the time, when Imperial supremacy was widespread, it was thought that only the "Imperial Cabinet" could issue orders and carry out this task in a short period of time.

He resigned in a short time due to differences of opinion with GHQ, but during that time the surrender document was signed aboard the USS Missouri on September 2. In November of the same year, Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko announced his intention to leave his royal status in order to take responsibility for the defeat.

In fact, in October 1947, he renounced his imperial status and took the name Higashikuni Naruhiko. At that time, Tarama also renounced his imperial status. Life after that was tough, and he seems to have survived by selling off the assets he owned as an Imperial family. Four years after that difficult renunciation, he made a spectacular move to Brazil.

* * * * *

Because his grandfather was active as a leader of the "military-military unification faction" during the late Edo period, he was historically excluded from the mainstream of the new Meiji government, despite being a member of the imperial family.

After the war, when SCAP ordered the end of the war, he became the Prime Minister of the first "Imperial Household Cabinet" in modern history to disarm the Japanese military, took command of the end of the war process, and was the first to leave the imperial family.

Tarama may have had a kind of resignation towards the bloodline that has been used historically in this way, such as the way that it has been elevated to the position of imperial family that stands in opposition to the mainstream, which has appeared at important turning points in modern Japanese history.

Of course, not all of the "nobles" who emigrated to the other side of the world achieved great things like in the novels about the wandering nobles. They were just like ordinary people, but because of their lineage, people expected them to have "something more than the average person," and they lived as ordinary immigrants, searching for their own kind of happiness in South America.

© 2015 Masayuki Fukasawa