The black person is the protagonist in most of my paintings. I realized that I didn’t see many paintings with black people in them.

—Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988)

One thing that I have learned in my own ponderings about my identity of which “Nikkeiness” is a significant part, it is that tracing the sources to the essence of who and what we are is not always easy.

This really struck me on a recent visit to see an outstanding exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto of the NYC artist Jean-Michel Basquiat whose own struggles with identity as a young Black artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent, skin colour, stereotypes, economic and social (e.g., police brutality) issues all burst through the jagged edges of his remarkable work. For the socially attuned Black artist then, there is no escaping all of this. But what about for the Asian artist?

Think back to the last time you saw an Asian as a protagonist of a painting?

R-A-C-E is a four letter word that we Asians don’t discuss much.

Rarely, do our respective community organizations ever speak up (e.g., murdered and missing aboriginal Canadians), when they are called to do so. Have we really evolved into those dreaded ethnic elites who are somehow above issues of “race”, believing all of those “nice” model minority myths about us that the media reported in the 1990s?

These days, discussions of identity are virtually absent from our own media. While Black issues are talked about, discussed, and debated in the mainstream media, we Asians seem content to hide our own experiences of racism and the rest of society is content with the stereotype of Asians as decent student and successful in the workplace. So, what’s the problem?

How often does the issue of racism come up in our Nikkei media? Rarely. If we don’t shatter these myths then are we cursed with living with these stereotypes?

Sadly, not much has really changed since the Redress Victory in 1988. As we have become more integrated into the socio-economic mainstream, our “Nikkeiness” too has become more mixed through intermarriage, and what seems to now be commonly held beliefs that our experiences of systemic racism and persecution, especially before, during, and immediately after World War Two, are part of a regrettable and now better forgotten past which has whitewashed away important truths of who and what we are. So many of our communities have lost their direction, failing to evolve into meaningful, ethnically similar groups that foster and support an evolving sense of Nikkeiness.

To that end, I see our Nikkei artists as being uniquely placed to help our national community regain a meaningful vision that our estranged youth in the post-Redress era will feel compelled to connect to and make being Nikkei relevant again.

* * * * *

First of all can I please get some info about your age, education, where do you live, what do you do for work?

I’m 32 years old and was born and raised in Toronto, Ontario. I went to the University of Guelph for my BA in studio art and psychology and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln for my MFA, where I specialized in printmaking. I’m back living in Toronto now, making and exhibiting work and teaching printmaking courses at the Ontario College of Art and Design University and Open Studio, an artist-run printmaking centre.

Can you please tell me about your Japanese Canadian side of the family?

My father’s side of the family is Japanese Canadian. My paternal grandparents were both born in Vancouver, however, for different reasons they also both spent a significant portion of their youths, growing up in Japan.

My grandmother’s parent’s owned and operated a rooming house in Vancouver’s Japantown. One of three girls, my grandmother, born in 1923, was raised alongside one of her sisters, by her paternal grandparents in Japan from 1929–1937. At the age of 14, she returned to Vancouver from Japan, progressing through school, learning English, and also how to sew clothing. In 1942, the government seized the rooming house, fishing boat, and all other family property and the family was sent to Slocan, where they were interned.

The middle child of three boys, my grandfather was born in 1920. His parents decided they wanted to return to life in Japan, thus, the family moved to Japan in 1929. In 1939, when my grandfather was 19, he decided to return to Canada, encouraged by his older brother who had already gone back to B.C. and found work. Then in 1942, he was sent to work on the Revelstoke-Sicamous Road Project, working to build fifty miles of the Trans-Canada Highway.

Both in their early twenties when they were sent to the interior of the province, my grandparents met either in Slocan or while working on a ranch in Vernon where they were both working at the end of the war. Either way, they were married in November of 1945 and my father was born a year later. In 1948, the family moved east to Hamilton and had two more children.

It seems that making sense of their internment experience is a major theme of your work?

For the past six years, my work has continually sought to address and investigate the broad themes of memory and loss, as well as specific family stories, inherited narratives, and the many complex layers they possess. Growing up I listened to and learned of the complicated stories that surrounded my paternal grandparents’ lives—captivated by their childhoods spent between Canada and Japan and then forever haunted by their internment during the Second World War and their years following that time. These stories have stayed with me and have been the focus of much of the work I’ve made over the last six years.

What kind of sense have you made out of internment and how it affected your grandparents? Is this a legacy that you inherited in some way too?

It is hard to make “sense” of the internment and I’m not sure that I ever will. I know that it had a profoundly deep impact on my grandparent’s lives. Seventy-two years later, the impact of the internment continues to mark what it is to be a Japanese Canadian, with the reverberations being felt by each subsequent generation, who struggle in their own way to locate this narrative within both individual and collective identities.

How open were your grandparents about their internment experience? Did they tell you stories? If so, can you share some?

I was thirteen when my grandfather died and I don’t remember talking with him about his childhood, his years in Japan, or about his experiences during the war. He was a lovely, kind man, but quiet too. All that I have learned of his life, has been pieced together from what my grandmother, mother, and aunt have told me. Of my grandmother’s experience—I was twenty-two when she died, so we were able to have some good years of storytelling. I learned of her years in Japan and I knew the rough details about her internment experience. We would sit and look through photo albums and she would describe different images. But looking back and trying to separate out what I know now, from what I knew then—it’s all become a blur. Back then—I’d say her stories were just that, a narrative that provided a framework of her life, small details and snippets. But I don’t ever remember having a bigger discussion about how these events impacted her life. There are many questions I wish I could ask now…

Do you think that racism is still a relevant issue for Canadian Nikkei in 2015? If so how, why?

Growing up in Toronto I’ve had the opportunity to live in an incredibly multi-cultural city, where there is a great awareness and respect for people’s varied backgrounds. For me, being Nikkei is simply a part of who I am. It’s about where a part of my family has come from and what their experiences have been. Being of mixed race in 2015 is to be a part of the ever-growing global community.

As to racism—yes, I think it is absolutely still an issue for Canadian Nikkei in 2015. Racism has certainly been present in my life—for the most part, I’d say that it’s not an issue and that I am able to just be myself in the world. However, at other times I feel very much that I am being viewed and treated as other. It’s a complex issue that has many layers and I will no doubt have to continue to navigate it throughout my life.

What informs your “Nikkeiness”? As a woman artist? Canadian?

My work and my research have had a profound impact on my understanding of my “nikkeiness”. Learning more fully about my family’s stories and the wider history of Japanese Canadians, has informed what it means to be both Nikkei and Canadian. I’ve traveled out west with my family, completing a pilgrimage of my grandparents’ and father’s journey—locating those narratives within the landscape and bearing witness to those tales. Being able to grapple with these histories through my work has pushed me as an artist and furthered my own sense of self.

Can you please talk a bit about your mom’s side of the family too? How has each side informed the other?

My mother’s side of the family is Scottish Canadian. Both sides of my family significantly shaped who I am. Questions and issues of identity and race didn’t factor into my childhood very much. My parents were just that, my parents. And my grandparents, known as “Baba and Gramps” and “Baachan and Jiichan,” were an extension of my nuclear family. Everyone had their own experiences and as I grew up alongside my sister, I listened to stories about lives lived, struggles, successes, and family histories.

Can you trace the evolution of your interest in your Nikkeiness? Did it start from a young age? Who influenced this evolution? Grandparents? Parents?

My interest in my “Nikkeiness” and heritage on both sides of my family has its roots in my fascination with family stories and my desire to learn and hear about my family’s history. The lived experiences of both sets of grandparents impacted all subsequent generations of my family. Their stories, as well as the retellings of those stories by my parents and extended family have propelled and encouraged my research and investigations to where they are today.

What role has your ethnic identity played in your evolution as an artist?

My family’s history has played a large role in the evolution of my art making over the last six years. My research and investigations into these specific family stories have guided the direction of my work thus far, providing many opportunities to delve deeper and examine questions regarding the issues of identity and belonging. It will be exciting to see what lies ahead and what questions will arise next.

Have other Nikkei artists influenced you? If so, who and how?

I would have to say Joy Kogawa has been the most influential Nikkei artist for me. Her written voice found its way into my own memories, merging with what I thought had been my grandmother’s experiences…conflating and blurring over the years, so that when I re-read Obasan years later, I was utterly surprised at how much my own memories had altered. The strength and beauty of her words, as well as their prominence in the wider community demonstrates how art is capable of inspiring conversation and continually engaging other audiences.

Does being an artist give you any particular freedom to explore who and what you are? Are there still areas of particular interest that you want to explore?

Absolutely. To be able to do what I love and explore the topics that I’m deeply interested in is a wonderful gift and an incredible freedom to have. What lies ahead in terms of new work and new topics to delve into—I’m not sure. Each project and body of work seems to open new doors and other possibilities, so I will see how things unfold.

What do you hope that visitors to the JCCC group exhibition get from the experience?

I hope visitors will enjoy the introduction to four different Nikkei artists. Working within a variety of media and delving into a range of ideas, this group exhibition shares insight into how different artists create and think about art and lived experience.

With regards to my own work, I have sought to create an environment that opens the space to share stories—in which different ways of seeing, of researching, of telling and of hearing a story can be experienced. By drawing attention to the fragments and layers left behind, the weight of what cannot be recovered or remembered is revealed. And by investigating how stories are used in the construction of a geography that can be grasped, I am able to explore where that narrative fits within my own sense of self, family, and community.

Description of Works in the show

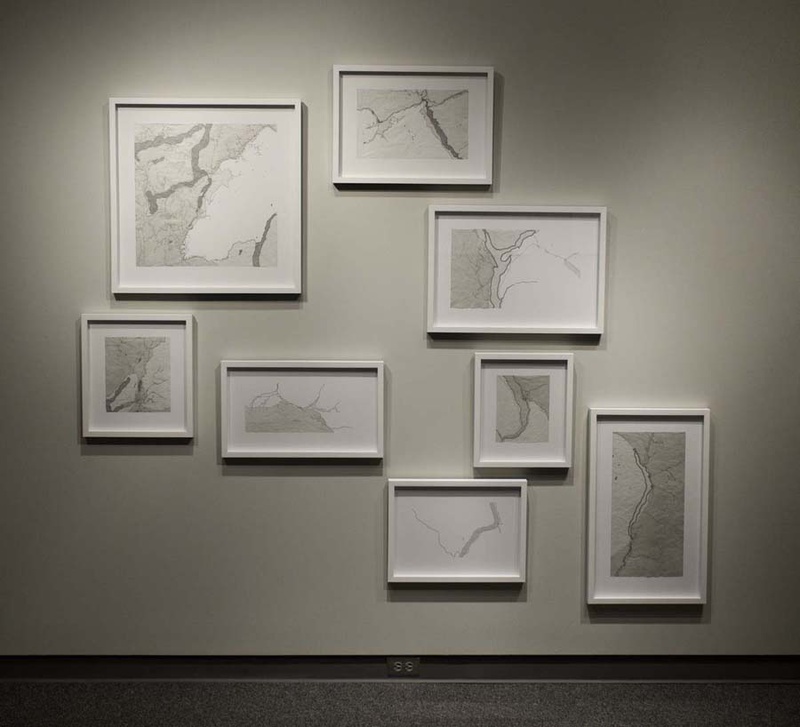

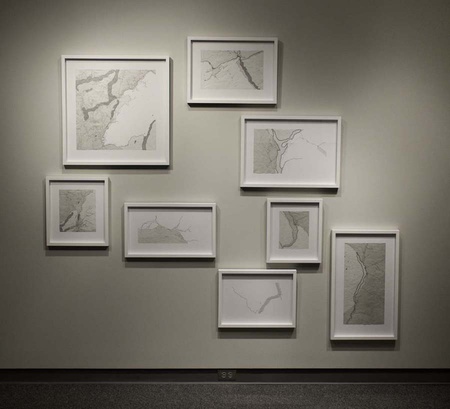

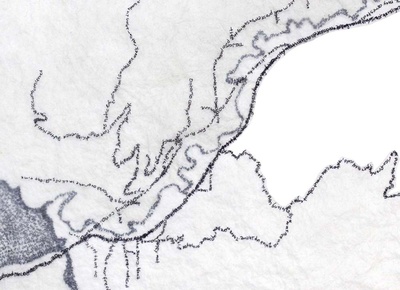

1. Constructed Narratives

Locating memories, collecting stories, and working through all that is not remembered, this work investigates a geography of story and its layered and complicated meanings.

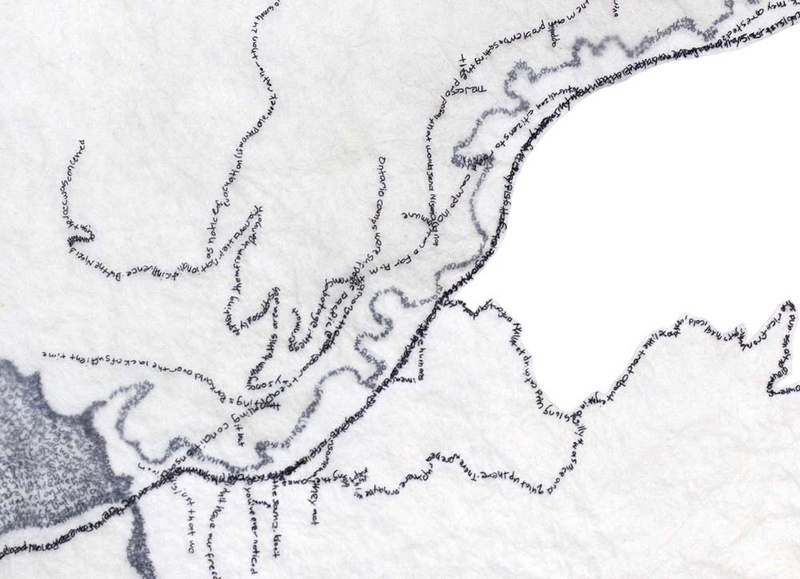

Mapping the spaces and landscape in which my paternal grandparents lived and worked between 1942 and 1947, these prints explore a set of interconnected roads, rivers, and lakes within the interior of British Columbia. Focusing on several different locations of Japanese Canadian internment camps, including Slocan, the camp where my grandmother was interned, the map also details the section of road my grandfather was sent to work on during the war years.

Each piece flows into the next, highlighting cities, towns, and communities, one of which is Vernon—the city where my father was born shortly after the war ended. Paths, roads and bodies of water, connect and break away. Fragmented and veiled, they whisper of a story, almost unreachable and unknowable, but there nonetheless. Working with historical and contemporary writings as well as novels that have shaped my encounters and understanding of this time and place in history, the maps are composed of various passages and chapters of transcribed texts.

As the geography changes, so do the stories, revealing the historical climate of the day, first hand accounts of the internees experiences, fictional tales, as well as a look at how the landscape was and still is encountered. An exploration of the physical map of experience, this work traces different paths, journeys, and pilgrimages of three different generations of my family.

Adachi, Ken. The Enemy That Never Was: A History of the Japanese Canadians. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 1976. 240–42, 251–74. Print.

Broadfoot, Barry. Years of Sorrow, Years of Shame: The Story of the Japanese Canadians in World War II. Toronto, New York: Doubleday Canada Ltd. and Doubleday & Co. Inc., 1977. 156–62. Print

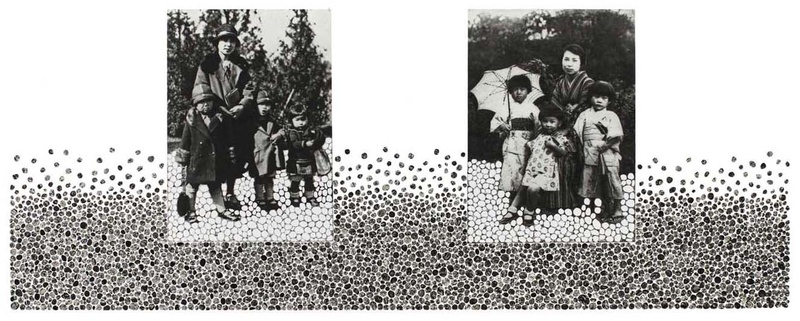

2. In-Between Worlds

Family stories are told and retold, evolving over time with new details and other layers. Towards the end of my grandmother’s life, she lived in these stories; they were her reality, her present. The past had become her most vivid world. And so upon visiting her, my sister, mother, and I would listen to her stories, and bear witness to her memories.

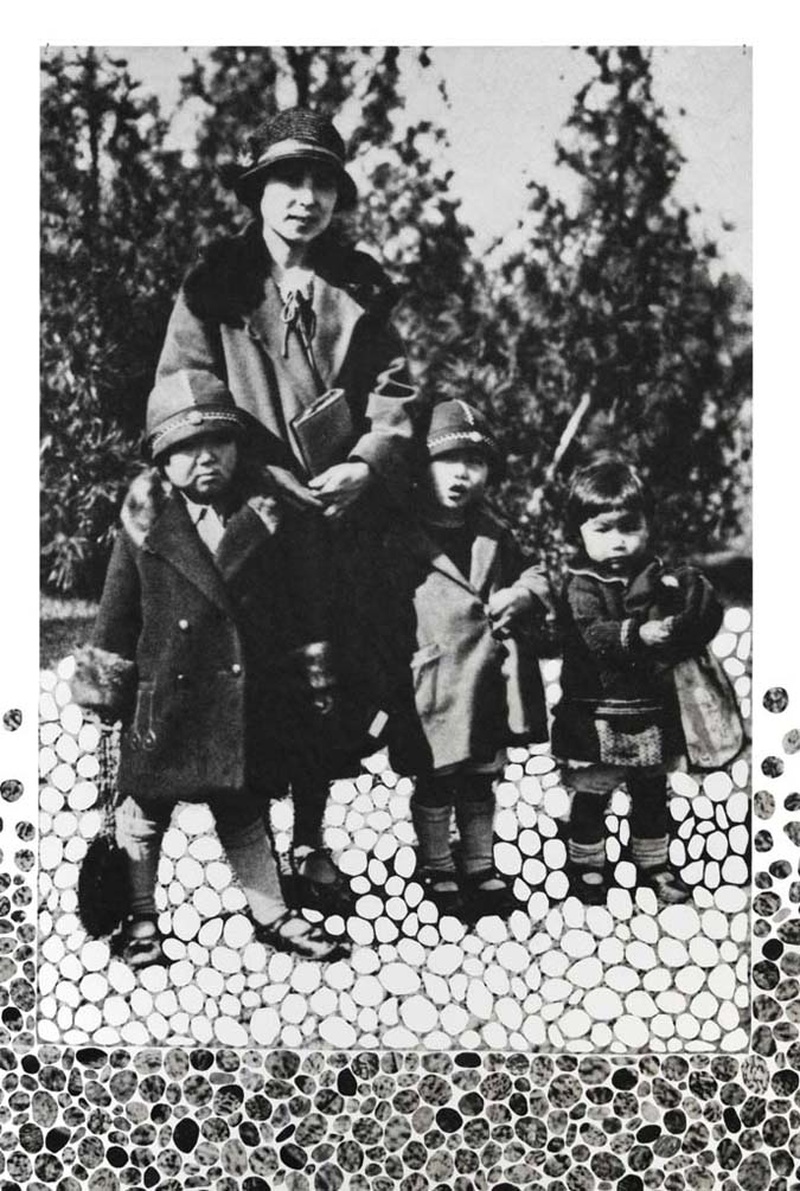

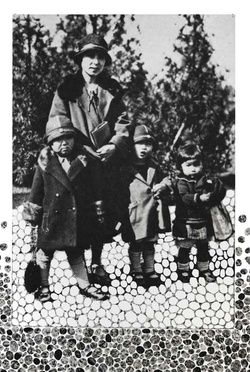

Born in 1923 in Vancouver, my grandmother, Mary (Miyeko) Matsuoka, spent the first six years of her life growing up alongside her two sisters in the rooming house her parents operated in Japantown. Then in 1929, she travelled to Japan with her mother, Hisae, and her sisters to live with her paternal grandparents in the small coastal town of Ugui located in southern Wakayama Prefecture. After a year or two, Hisae decided to move back to Vancouver with her daughters. Upon hearing this news, Hisae’s mother in-law said that one of her granddaughters would have to stay behind to help out in the kitchen. Unable to leave one of the girls on her own, Hisae left the two oldest, my grandmother Mary and her middle sister Chiye.

Seven years later, when Mary was 14 years old, she wrote to her parents and told them she wanted come back to Canada to live with them. Later that year, in 1937, her father came to pick her up. Chiye stayed on in Japan for another fifty years. This experience and early trauma marked my grandmother deeply; she would revisit this story often and over the years, I heard more about this experience than I ever did about the internment.

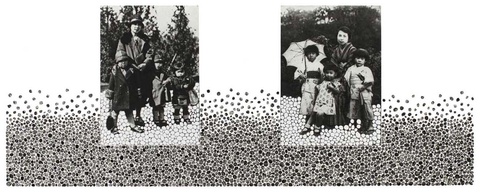

The piece entitled In-Between Worlds, was created using photogravure etchings made from two of my grandmother’s old family portraits: one of the family in Vancouver (around 1927), the other of the family in Japan (around 1929). What stood out for me in looking at these two photographs was that the pebbly ground that the family stood upon in both pictures was almost exactly the same—yet worlds apart. Investigating the ideas of belonging and displacement, of having and not having a space to call home, this piece blurs any sense of grounding within the two family portraits. A repeated story and a repeated form, where the traces of what have been are just as important as the re-telling and re-imagining.

3. Bundled Thoughts

After sorting through these old family stories and photographs, and the many complicated layers of history, I seem to have taken on some of their burden and acquired baggage that I cannot yet let go of. With the piece Bundled Thoughts, I have sought to explore my desire to understand the past, as well as the need to store and locate these memories. How does one sort, contain, and navigate the weight of individual and trans-generational memory? Is it possible for these fragile, elusive, and multi-layered stories to be made tangible?

Working with the traditional form of Japanese wrapping, known as furoshiki, I used the same photogravure plates from In-Between Worlds, printing numerous identical prints of these now familiar images and stories. Manipulating these prints into small furoshiki forms, only fragmented elements of the original photographs remain visible. For it is by drawing attention to the fragments and layers left behind, that the weight of what cannot be recovered or remembered is revealed.

© 2015 Norm Ibuki