Read Chapter 3 (2) >>

September without school - Autumn

The American school year ends in June, and after a long summer vacation of about three months, a new start begins in September. In September, children are given new clothes to match their height, which has increased over the summer, as well as notebooks and pencils, and look forward to reuniting with friends they have not seen for a long time. However, in September 1942, things were different for the Japanese-American children who had just been relocated to internment camps. From a letter written by Masao to his teacher, Mr. Wills, at Garfield High School, which he attended in Seattle:

Dear Dr Wills,

Now I am in the Minidoka Residence with nothing to do. I wanted to get a job, but the interviewer told me to wait until I graduate from high school. Speaking of school, it's nice for teachers to be able to teach students again who were looking forward to summer vacation only three months ago.

School here hasn't started yet. In fact, the school building hasn't even been built yet. The shacks we're living in now are going to be used as a temporary school, so we'll have to move again soon. How inconvenient.

As someone who loves school, it feels really strange to know that September will come and I won't be going back. It feels strange, or maybe I just can't explain it. I loved seeing my old friends at school again in September after the summer ended. I was so looking forward to that day. I get homesick when I think about that and everything about Seattle. After all, nothing beats Seattle and the Pacific Northwest.

Since reading books and studying are the only things I can do, I have read every book I can get my hands on. I want books so badly I want them so badly...

Student Masao 1

To buy new books : Autumn

Many of the books in the community library's collection were loaned from public libraries or discarded books, so new books were hard to come by. So librarians came up with creative ways to purchase new books. The Post Community Library distinguishes between paid and free books, with new bestsellers being paid books, which can be borrowed for 5 cents a week. Once the loan fees from readers reach the cost of the book, the book is placed on the free books shelf. The loan fees collected in this way are used to buy the next new book. The Post Press Bulletin claims that as of September 1, 1942, there were about 50 new bestsellers in stock. It's autumn, a time for reading. 2

Jeanne's Broken Father 3 ——— Autumn

In September, when the summer heat was still lingering, Jeanne's father returned to his family from the Manzanar internment camp at Fort Lincoln, a Department of Justice internment camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, where he had been held by the FBI for nine months after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The bus door slid open, and the first thing we saw was a walking stick poking timidly out of the darkness of the bus into the sunlight: a shiny, straight stick made of a maple branch, stained but polished, and pockmarked with black eyes.

Then my dad came down wearing a fedora and a tattered white shirt. … In the nine months that had passed, he had aged ten years. Leaning on a cane, protecting his right leg, my dad looked emaciated and lifeless, just like his shirt, like a man over sixty. …

This walking stick was made by her father himself while he was a prisoner of war, and was indispensable to him because both of his feet were frostbitten. He never said a word about the cause of the frostbite. After living with her father, Jeanne felt oppressed by the presence of her "bitter, pensive, gloomy father." She stayed in her room all day and had her mother bring her meals. She had her mother bring her extra rice and canned fruit syrup, and brewed alcohol in a homemade still, and drank all day until she was completely drunk, and in the end, she would become violent.

...There was a deeper, uglier reason for Dad's loneliness. I discovered it one night when Mommy and I went to the bathroom together. By that time, the bathrooms had been partitioned off. Just as we went in, two women of Mommy's age who had once lived on Terminal Island were coming out.

They were lingering in the doorway, and from the bathroom I could hear them whispering about their daddy, in hushed voices but loud enough for us to hear. They kept using the word "dog."

Jeanne would later realize that the word "inu" used that night meant "informer." We don't know what happened to Jeanne's father in the internment camp, but many Issei lost their dignity and authority as heads of households while in the camps, having lost their role as the family breadwinner.

School has started but it's autumn

Although the elementary school in the Topaz concentration camp opened, a large hole remained in the roof for the stove chimney, and the work of attaching the plasterboard to the interior walls had not yet begun in the classrooms. "I tried to teach a class, but a lot of dust and sand flowed into the room not only from the hole in the roof but also from everywhere, and it quickly became impossible to proceed with the lesson," said Yoshiko Uchida, who became a teacher. At the end of autumn, snow blew in through the hole in the roof, and even though the children were fully equipped with coats, scarves, gloves, and boots, their hands became numb and they could not teach. It must have been a very difficult situation for the children. The school was closed in mid-November and will remain closed until stoves and interior walls are installed. On a day when a sandstorm was so strong that even adults could not walk, Yoshiko wrote the following.

I was struck, as I always am, by the children's eagerness to learn, despite the desolate surroundings, the poor quality of teaching materials, and, in this case, the physical dangers that inevitably accompanied the journey to school. At the time, I was heartened by their cheerful energy, but I have since worried that the seemingly incurable emotional trauma caused by their forced removal from their homes might have inflicted an incurable wound on the souls of these young people.4

Bleeding Concerns — Autumn

Katherine Harris, a teacher at the Poston internment camp where Breed's children were in, recorded that in 1942 the annual salary was $1,620, and two years later, after the Native American Affairs Agency withdrew from running the camps, the annual salary for high school teachers was $ 2,000.5 Japanese teachers were paid a maximum of only $19 a month, or $228 a year, about one-tenth of the salary.6

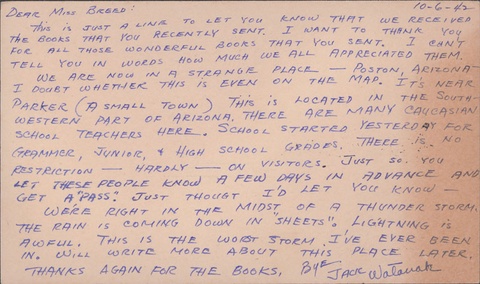

Below is a letter written to Breed from some of the children around that time. The word "white" was becoming more common, and it seemed as though all the children felt that white people were superior to second-generation Japanese. Breed worried that the difference in treatment of teachers would erode the children's self-esteem. In an article published in the Library Journal, she expressed concern about the impact of the government's racist policies on children, writing, "It seems a pity to me that racial attitudes should be so hardened among children and young people. Is this an inevitable pitfall of our eviction policy? Is it in keeping with our war aims?" 7

I'm really happy to be back in school with white teachers. Even though it's inside the camp, it's a normal school and I get credits for attending. I only have one year left until I graduate, but I'm honored to have this opportunity.

Margaret

School started last Monday. I felt sad that I had already graduated from school when I saw that all the students had their own chairs. There are about 20 white teachers in the Poston 3 Camp, and they come from various states, such as Oklahoma, New York, Virginia, and California. Most of the teachers are elderly.

Hair

Until Friday, there was only one Japanese teacher, but on Friday the principal brought in an American teacher. So, starting on Monday, we will have a new teacher. ... The Japanese teacher doesn't let the students study the language at all, and suddenly starts using difficult words.

Catherine

Notes:

1. Letter date unknown, Elizabeth Bayley Willis Papers. Acc. No. 2583-6, Box 1. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

Ms. Elizabeth Bailey Wills taught Art, Latin and English at Garfield High School.

2. Poston Press Bulletin, Vol. IV No. 5, September 1, 1942.

3. Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston, translated by Kwon Yasushi, "Farewell to Manzanar: A Record of the Heart of a Japanese-American Girl Who Was Incarcerated," Gendaishi Publishing, 1975

4. Yoshiko Uchida, translated by Kazuo Hatano, "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of a Japanese-American Family During the War," Iwanami Shoten, 1985

5. Harris, Catherine Embree. Dusty Exile: Looking Back at Japanese Relocation During World War II. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 1999.

6. There were three pay scales for Japanese Americans working in the camps: professionals at $19 per month, skilled laborers at $16 per month, and everyone else at $12 per month.

7. Joanne Oppenheim, translated by Ryo Imamura, "Dear Breed" Kashiwa Shobo, 2008

*Reprinted from the 135th issue (October 2013) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett