Read Chapter 2 (6) >>

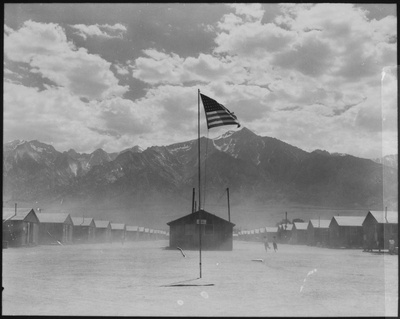

Once again, with preparations for their arrival incomplete, the Army decided to move the Japanese from the "assembly center" to a "relocation address" inland, far from civilization. After two days of sitting on hard seats in old, unused trains with the window shades down and covered in soot, the Japanese finally arrived at Minidoka from the Puyallup temporary camp, only to be greeted by a desert and sandstorm as far as the eye could see. 1

And these words appeared in the September 10, 1942, inaugural issue of the camp newspaper, the Minidoka Irrigator.

We are here not by our own will. But resistance cannot change the fact that we are here, nor can it erase the possibility that we will remain here until victory is won. We, ten thousand people, must resolve to do one thing: join forces and do all we can to transform this barren land into a livable community. Our responsibility is to squeeze as much normality as possible out of this abnormal situation. Our goal is to create an oasis. Our great adventure is to "repeat here the feat of the pioneers who fought against the earth and nature."

Our future is in our own hands, and there is no need to despair .

* * * * *

In the barren land as far as the eye can see, sagebrush is blown by the wind, curled up and stuck to the ground. 3 The only living things are sagebrush and desert animals such as snakes and scorpions. In the swamps of Lower and Jerome, there are swarms of ticks and mosquitoes. The climate is harsh, with temperatures reaching nearly 45 degrees Celsius in the summer and nearly minus 30 degrees Celsius in the winter. In the inland areas of Wyoming, Idaho, California, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and Arkansas, "improvised cities" with populations of over 10,000 people quickly appeared in 10 locations.

The War Relocation Administration (WRA) managed the camp, which had a similar system to a regular city administration, with a school, hospital, library, fire station, police, post office, etc. Just as in the temporary internment camps, the management of the camp was left to the Japanese, and a self-governing organization was formed with elected officials, and a consumer cooperative was also formed, which included a convenience store, florist, shoe repair shop, dry cleaner, watch repair shop, barber shop, beauty salon, radio repair shop, mail order service, optician, and even a fresh fish store.

Manzanar also had an orphanage called Children's Village, where nearly 100 children lived together. In addition to children who had been in orphanages in Los Angeles and San Francisco, there were also children who had been orphaned by their parents taken away by the FBI, and children born in internment camps whose parents could not raise them for some reason. The children attended school within the camp and had many friends outside Children's Village, but the director, Lillian Matsumoto, had promised the children that they would always eat meals together here. 4

| Change of address | Opening date | Closed Day | Maximum number of inmates | |

| Wyoming | Heart Mountain | August 12, 1942 | November 10, 1945 | 10,767 |

| Idaho | Minidoka | August 10, 1942 | October 28, 1945 | 9,397 |

| California | Manzanar | June 1, 1942 | November 21, 1945 | 10,045 |

| Tule Lake | May 27, 1942 | March 20, 1946 | 18,789 | |

| Utah | Topaz (Central Utah) | September 11, 1942 | October 31, 1945 | 8,130 |

| Colorado | Amachi (Granada) | August 27, 1942 | October 31, 1945 | 7,318 |

| Arizona | Poston (Colorado River) | May 8, 1942 | November 8, 1945 | 17,814 |

| Gila River (Hela) | July 20th, 1942 | September 28, 1945 | 13,348 | |

| Arkansas | Lower | September 18, 1942 | November 30, 1945 | 8,475 |

| Jerome | October 6, 1942 | June 30, 1944 | 8,497 | |

| Reference: http://www.janm.org/jpn/nrc_jp/accmass_jp.html | ||||

1. 1942

Child concentration camps : Summer and fall

I found Bacon Sakatani's essay, which vividly describes the lives of the children, in a collection of photographs of the Heart Mountain concentration camp by Bill Mumbo. The photographs were taken with Kodachrome, which had just started to be used at the time, and are in color. I will show you one of the photographs a little later, but first, let Bacon, who turned 13 years old, talk about the daily life of the children on the train from Pomona, California, to Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

The room for a family of seven was 6m x 7m. It had one light bulb, a coal stove, a mop, a broom, and a bucket. If you put seven military cots in the room, it would be too big to fit anything else. Luckily, it was close to the dining room, toilet, and laundry area.

At first, we ate together as a family, but soon there were groups of children who ate by themselves. I would wake up in the morning, go to wash my face, go to the dining hall, and either eat breakfast by myself or with my friends if they were there. As the youngest, my job was to sweep and mop the room and keep the coal bucket full for the stove. The coal was piled up next to the barracks, so I just had to go there and refill it. After that, I would play with my friends all day.

But we couldn't go beyond the barbed wire fence, so we made shields out of cardboard boxes we found behind the cafeteria, and threw mud balls at each other with our friends, and explored every nook and cranny of the camp, which now has 20 blocks and a population of 10,000. Once, when we treated the youngest child in our group a little roughly, the child's parents complained, and we were severely scolded by the police chief. Luckily, the parents were not informed of the incident.

There were watchtowers around the camp, but sentinels with guns stood there only at night with big searchlights. In early autumn, snow came early, and we gathered scraps of wood to make sleds. We went sledding on the only hill in the area, which was just outside the fence. It was full of kids. Years later, I heard that one day, 32 kids were sledding on the hill when the Army police showed up and hauled them away for straying from the camp. It must have been scary. But I'm a little sad that I had been there, because I could have told them my heroic tales now... 5

When 9-year-old Gene arrived at the Gila River Internment Camp in Arizona, he experienced the beautiful desert night sky, something he had never seen before. His older brothers slept outdoors, looking up at the stars. However, Gene was afraid of wolves, coyotes, rattlesnakes, and scorpions, so he never slept outside. However, he would climb the same rocky mountain with his older brother Goro to watch the sunset, and go on desert explorations with his friends.

It was September, and the weather was mild. The sky was crystal clear, and the night sky was filled with more stars than I had ever seen before. The stars were bigger and brighter than those I had seen in California, and in one corner of the sky they formed a band as if someone had walked around spilling talcum powder on them .

Next is the adventure story of Takayo Tsubouchi, who laughs, "Looking back, I guess I was braver than I thought I was, or maybe I was just a little bit smarter..." One day, when her husband was hospitalized with pneumonia, she said, "I was sitting by his bed with nothing to do, so I decided to write down my memories of that day. I'd never written anything before."

"It hurts, Sis. Don't pull so hard." I couldn't help but cry out as she pulled my hair. It happened when my sister was braiding my hair in the sunshine. I started to tell her what had happened that day. "Don't get mad. I'm going to tell you about the adventure I had today. I want you to listen, Sis. But don't tell Mom and Dad. I don't want you to get scolded because of me. I'm sorry I made you worry today. I won't do it again. It was the first time, I really do," I began.

It was a beautiful day. I was standing next to the railroad tracks. A train went by and I waved to the conductor in the last car. I wanted to ride that train and see what I could see from the window. I wanted to see more than just the shacks covered in black tar paper. Yes, I was being careful. There was no one around so I walked under the barbed wire, across the tracks and for a while. There was nothing to see. Nothing pretty. No grass, no flowers, no trees. Just a long dusty road. The sun was shining brightly and it was really hot. I looked into the distance and saw a sparkling lake at the end of the road. I was thirsty, hot and tired but I kept walking because I thought if I went a little further I would see something pretty. Then I saw a dusty narrow road, a small hut, trees, grass, and a dog, so I followed the narrow road. When the dog saw me, it wagged its tail happily. It came running to me and let me stroke its head. It had been a while since I had seen a dog. Sister, I remembered the dog I left at home.

The shack was really tiny. It was a small country grocery store, and I wondered who would shop there. There were no houses around. It was a little bigger than the outhouse we had in Hardwick. Sister, this shop is worse than our shacks. The floor was mud. When I walked in, the hot sun shone through the gaps in the wallboards. But inside, it was dark, and there were no light bulbs. The shopkeeper, his wife, and their two children, a boy and a girl a little younger than me, were there, and they were staring at me like they were going to burn a hole in me. It was a little scary, but I guess they had never seen a child like me, an Asian child. Well, I'd never seen a black person before, so I just stared at them with my eyes wide open. ...We looked at each other for a long time, and then just then they smiled at me, and I smiled back. I wanted to buy something here, but I didn't have any money. I figured the food and drink here would be a lot better than what I had in the camp cafeteria. They were really nice, Sis. They gave me candy and soda. It was really good. Of course I said thank you. We didn't talk much, just looked at each other and smiled. I didn't stay long, I said goodbye quickly and skipped/walked/run back towards the camp.

I was so happy that I didn't pay attention to my surroundings this time. I was trying to sneak into the camp when I saw the jeep. There was no ditch by the road, no bushes to hide in. The soldier had a gun and looked scary, but he was a nice guy. He even helped me get under the barbed wire. I didn't want to be found by a scary soldier in a high guard with a machine gun. Hey, don't worry, sis. I was fine, I got out of the camp, and I had a great day. 7

Notes:

1. Monica Sonne, who had just arrived in Minidoka, described the sand storm as being like being inside a motor-driven concrete mixer drum filled with sand.

2. Yasuko Takezawa, "Japanese American Ethnicity: Changes through Internment and the Reparations Movement," University of Tokyo Press, 1994. The Minidoka Irrigator, Vol. I No. 1, September 10, 1942.

In fact, there was another way to welcome the Japanese-Americans. In the writings left by Nakagawa Kichiyo, wife of the principal of the Seattle Japanese Language School, there is a description of the time they arrived at Minidoka. "It was a misty, chilly morning on August 31, 1942. We arrived at Minidoka the next afternoon on a specially made train. There was no railroad to the camp, so we changed to a bus on the way. What surprised us was that so many white people were there to welcome us. It was a heartwarming first impression, as if there were people who would welcome us, such unfortunate people. However, that was not the case. Apparently, the white people, who had never seen a Japanese person before, had come to see us, thinking that we might have horns or something. We were made to laugh at this story that could be found in a remote part of America." They must have thought that Japanese people had horns after seeing the anti-Japanese cartoons in the newspapers. This episode is included in Ito Kazuo's "American Spring and Autumn Eighty Years."

3. An evergreen shrub found in the desert, sometimes translated as mountain wormwood.

4. Lindquist, C. Heather (ed). Children of Manzanar. Independence: Manzanar History Association, 2012.

5. Muller, Eric L (ed). Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

6. Gene Oishi, translated by Someya Seiichiro, "Torn Identity: The Life of a Japanese Journalist," Iwanami Shoten, 1988

7. Takayo Tsubouchi Fischer, interview by Sharon Yamato, October 25, 2011, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

*Reprinted from the 135th issue (October 2013) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett