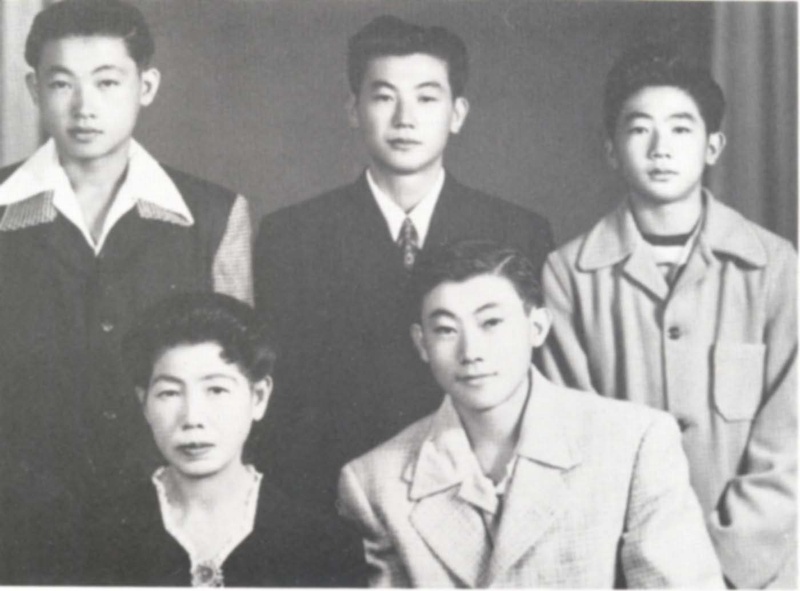

When the war came to a close, many of our friends started to leave camp. My brother Yukio just seemed to disappear at the first call—he went to Chicago to make his fortune. He found a job in one of the finer hotels as a busboy and was making a very good salary since that hotel catered to the very wealthy. My brother Taketo left for Los Angeles to make up for lost time and wanted to make as much money as possible. The only secure independent job to be found was as a gardener. My sister Haruko, who was married in Manzanar to John Ikkanda, went to Reno, Nevada with their child Janice (Chico) who was born in Tule Lake. My mother, my brother Iwao, and I left Tule Lake and arrived in West Los Angeles on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1945. It was a very sad Christmas Eve.

My father went back to Japan to see our oldest brother Hideharu who was living in Osaka, Japan. He was ill at the time and passed away before I ever saw him. It wasn’t until the Korean War that I saw my father again. He was living in Hiroshima when I first visited him and was raising both my niece and nephew, Hideharu’s children.

Our family was completely split up. The first night back from camp, and for the next few days, we slept in a trailer that belonged to Mr. Ikkanda. We ate all our meals at our friends’ (Kobayakawa) boarding house where my mother found a part-time job. Since our family was originally from West Los Angeles, my mother was able to find a room for the three of us at a friend’s place on Purdue Avenue. We were fortunate to live in that house until we were able to locate a place on Cotner Avenue. Iwao found a part-time job with a doctor as a student house boy. I remember Iwao giving me “kozukai” (allowance) until I found a job. I was fortunate to find a job at a golf practice range. I became very adept at picking up balls and was earning a lot of money. I was paid $1.60 per box, which I was able to fill in an hour. This was a part time job and paid very handsomely until my brother Tak found a rental home for all of us and asked me to help him with his gardening route. This was hard work but Tak was paying for the food and rent. Yukio, who came back from Chicago, also helped pay the rent, and since this rental home was so small, we found a bigger place on Missouri Avenue in West Los Angeles.

When I first came back from camp, I entered Emerson Junior High as a 7th grader. Since I was 14½ years old, the school officials wanted to know why I was still in the 7th grade. I had quit American school in Tule Lake to study Japanese because my father was planning to take me back to Japan since I was the only one that had never met my oldest brother in Japan. Anyway, after a few examinations, I was able to skip a year. I entered University High only a year behind in my studies, but since I took nothing but solid courses, I was able to skip a half-year: thus I graduated only a half-year behind. At Emerson, many of my friends who lived in W.L.A. formed a club which was called WLA Knights; it was very sports minded at first but later became a social club. The club changed its name to “San Souci” which meant “without a care.”

There were very few incidents of people picking on us, and this was probably due to our friendship with the Mexican Americans and our large Japanese American population. One incident I remember quite vividly was when I was shopping in Westwood. A man in his late fifties called me “a dirty Jap” and asked me what I was doing shopping in Westwood. I must have been about 16 years old then and a little hot headed, so I chased this man into a drug store. This old man ran behind the counter. I said, “I’m going to kick your butt.” The clerk intervened and asked me not to beat him up; he made the guy apologize to me…man, was I mad!

Another funny thing that happened at Emerson was when a guy named Sullivan, who was in my class, asked me if I was really Japanese. I said, “Yeah, I was born in Sawtelle.” He said, “You really don’t look like those guys in the funny (comic) books. How come you guys aren’t wearing glasses and none of you have buck teeth?” I called all my buddies and we laughed like crazy. Sullivan was from Montana and had never seen a Japanese in his life.

When we first got back to Sawtelle (W.L.A.), there was a lot of land where many Japanese were farming. The homes were being built a block at a time, making room for many others. In 1949, our family bought a house at 1934 Armacost Avenue for $10,500. The payment came to $70 per month. When I first went to work with my brother, he had a ’34 2-door Ford sedan. He had to take out the back seat and put all his tools in the back. At that time we didn’t have a gas engine mower; it was a push mower. The very first time I pushed a mower, it was quite difficult. We did everything by hand—cut grass, edged, etc. While living on Missouri Ave, I learned to drive, and by the 11th grade Tak had bought a 1941 Chevrolet and I was given the 1934 Ford, which I drove to school and to different parts of L.A. I was a fast driver and rear-ended many cars, but the drivers were very nice and did not sue or ever get angry with me.

I graduated in Winter, 1950, at 18½. Since I had very little money put aside, I decided to forego my higher education and go to work for a while and then enter college. But in June, 1950, the Korean War broke out, altering my plans again. I found out I had about a year before they would draft me, so I continued gardening. In November, 1951, with a few of my buddies I volunteered for the United States Air Force.

At the end of the Korean War, I was able to work on papers to get my father back to the states from Japan. He returned to the United States in 1954.

My mother was a very strong willed person who set certain standards for me to observe. She valued hard work, honesty, respect for others, and trust. I remember when she asked me, “What do you want?” I gave her a list of many material things that I wanted. She said, “If you want all these things, go find a job.” So I did. She never complained about what I bought. She also believed in giving 100% to whatever one did.

She earned a living as a domestic, cleaning homes until her early 70s. It was probably due to her years of hard, physical labor that she was able to bounce back after breaking her hip in a fall in the bathtub at about age 83 or 84. Not only that, she went back to walking daily to places like Yamaguchi Department Store, 3 miles roundtrip!

Her favorite pastime was Shigin (Japanese singing based on Chinese poetry). She was also a very good masseuse. At our home, she had many Issei men and women come over for massages.

She was very thrifty (like most Issei parents), and she was able to give all her children a small sum of money in her last remaining years. Although she had little education, common for Issei her age, she had foresight and an uncanny understanding of the economic system of our country.

She was a very religious person and belonged to the WLA Buddhist Temple and Seicho-no-ie (The House of Long Life) and, true to its name, she lived to 102 years of age. She passed away early in the morning of her 102nd birthday. We believe her longevity was due to her strong will, years of hard work, and deeply religious lifestyle.

A great source of pride for her and for us was when she was selected to be one of the first Issei to receive redress in person in Washington, D.C., at age 99.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices, Resettlement Years 1945-1955 in 1998. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 1998 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California