*Editor's Note: This article was written in 2004 and Fugetsu-do is currently celebrating its 112th anniversary.

My grandfather, Seiichi Kito, was born in Gifu, in Central Japan. He came to the United States in May 1903 and went to where other Japanese immigrants were – in the East First Street district of Los Angeles (now known as Little Tokyo). The Japanese population numbered 3,000 and, by November, my grandfather started producing sweets and opened Fugetsu-do with a couple of friends. As his business partners passed away, my grandfather found himself managing Fugetsu-do for the next 25 years.

Even on rainy and windy days, my grandfather would deliver his sweets. He carried manju and mochi around in a pouch, much like a backpack. He would also distribute the Rafu Shimpo, which was free in those days. Often people who wanted to pick up a copy of the Rafu, which also began in 1903, would buy something from my grandfather as well. So from the earliest days, the Kito and Komai family business were helping each other out. As time went on, products from Fugetsu-do were in demand up and down the coast of Southern California.

And, as Little Tokyo flourished, so did Fugetsu-do. Fugetsu-do’s success was largely due to the hard work of the entire Kito family. An early account tells of my grandmother running the front counter with her six children in tow. Not only the Kitos, but my grandmother’s brother. Sakae Sakuma, was very instrumental to the early success of Fugetsu-do. This labor-intensive business kept members on both sides of the family quite busy.

As fate would have it, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcing the evacuation of all people of Japanese ancestry. They had between four days to two weeks to wind up their affairs before reporting to the Civil Defense Centers for transport. My family had to liquidate their inventory. News spread to other parts of Los Angeles that “good deals” could be made in Little Tokyo where the Japanese Americans accepted any offer for their property. My father remembers these “bottom feeders” offering five cents on the dollar knowing the Japanese Americans had no choice but to accept. And, what my family couldn’t sell, they put into storage.

My family was sent to an internment camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. When word spread around that my grandfather was a pastry chef, fellow detainees provided him with their sugar rations, so he could make mochi and manju for them. It was at Heart Mountain that my father met and married my mother, Kazuko. After the war, as the Japanese Americans were being released, the War Relocation Authority encouraged them to move to other locations in the U.S. to minimize hostility, but there was never any question in my grandfather’s or father’s mind where they would go – they would return to Little Tokyo. And, they did.

Upon their return, my parents struggled to reestablish the family business. First, they had to retrieve equipment, but the property owner demanded four years of back rent for storing it. When my family couldn’t pay, he kept their machinery. For a time, my parents slept at Koyasan Temple while my father worked as a waiter making 20 cents an hour, and on Boy’s Day, May 5, 1946, he re-opened Fugetsu-do on East First Street, with the help of the Tanahashi family. The store briefly moved to Second Street for a couple of years and then reopened at its current location on First Street with my father, Roy Kito, as the sole owner.

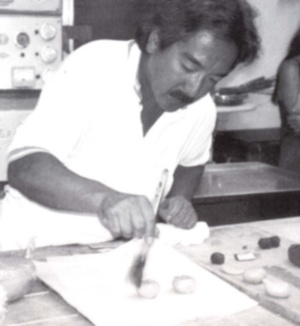

I must have inherited some entrepreneurial skill because, as a teenager, I leased the soda fountain at the family store and began my own snow cone business. It was a big hit during the annual Nisei Week festivities. Eventually, in 1980, I decided to continue the family business and promised to get it to 100 years, and I’ve dedicated myself to the promise made ever since.

Although the number of visitors to Little Tokyo had decreased in the past several years due to the economic situation in Japan, I count the local Buddhist Temples and the Japanese grocery stores as regular customers. Japanese holidays such as New Year’s Day, Girl’s Day (March 3), and Boy’s Day (May 5) also bring an influx of extra business, as special mochi and manju are made for those specific occasions.

Many times over the past several years, I have contemplated remodeling the shop, but each time, I hesitated. Yes, the shop looks old and dated, but that is what our customers remember. I have come to realize that Fugetsu-do has been around for 100 years not only for my family, but for our employees and customers as well. Last year, I received a request from a bride-to-be in San Francisco. She wanted her wedding photos taken here at Fugetstu-do. I obliged, not completely understanding the young woman’s motives. It was from the bride’s mother that I got the full story. The young woman had been very close to her grandmother, who had recently passed away. Most of her memories of her grandmother were of coming to Fugetsu-do together. For this young woman, my family shop represented a spiritual connection to her grandmother. This is just one story of why I hesitate remodeling and updating the shop.

There are many more stories that I could share. I could talk for hours about the “all-nighters” spent making mocha during the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day – not only with the Kito family but all the relatives, employees and friends were involved in filling orders. Even today, cousins send their children to help me during the New Year’s rush. It’s almost like a rite of passage for the members of our family to work at Fugetsu-do during the New Year’s season. It’s as if the older generation wants the younger generation to experience what they did so we can all share stories and have a common thread that can tie all of our family members – young and old – together.

Although the art of mochi and manju making has a long history in Japan, I try to keep my eyes focused on the future as well. In celebration of Fugetsu-do reaching its centennial, I crafted a new product – a strawberry flavored mochi with peanut butter filling.

Recently, I received a letter dated July 16, 2003 from Tony Yue, a member of the Chinese Historical Society of New England, located in Boston, Massachusetts. The timing of the letter could not have been more perfect. All along, my family has made the claim that it was my grandfather, Seiichi Kito, and not a Chinese, who created the fortune cookie. In his letter, Yue talks of finding a 1927 article from a California magazine, which confirmed the fortune cookie was invented by a Japanese American living in Los Angeles, and that the cookie was copied and popularized by the Chinese American proprietor named David Jung, the first mass producer of the fortune cookie.

Fugetsu-do has made it to its 100th anniversary. However, the road my family has taken over the past century hasn’t been completely smooth. Yes, we struggled, and yes, there was suffering – a lot of it, not only within the family, but in the community as well. But there has always been a sense of camaraderie at Fugetsu-do, through the good times as well as the bad. Anyone who has ever worked those “all-nighters” has fond memories of the experience. My family business could not have reached its 100th anniversary without the generations of customers and employees. It is with their help that Fugetsu-do has been able to achieve this historic milestone.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices, Little Tokyo: Changing Times, Changing Faces in 2004. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2004 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California