... We don't know exactly what life will be like in the camp, much less where we'll go afterwards. But we'll be among 4,000 Japanese Oregonians being housed at the Portland Camp, a former international livestock showroom. With limited work options available, many of us will likely just waste our time in boredom. In such a crowded environment, parents' biggest concern is their children: how to protect them from harmful influences and how to guide them toward creative, constructive lives... 1

This is a letter that Andrew Kuroda wrote to a friend just before entering the temporary internment camp. For the Japanese Americans, the thing they were most concerned about was their children. Their family registration numbers were attached to the lapel of their coats and on their belongings, and the moment they passed through the entrance to the temporary internment camp surrounded by barbed wire, each person's name was replaced with a number, and they lost their freedom and dignity.

* * * * *

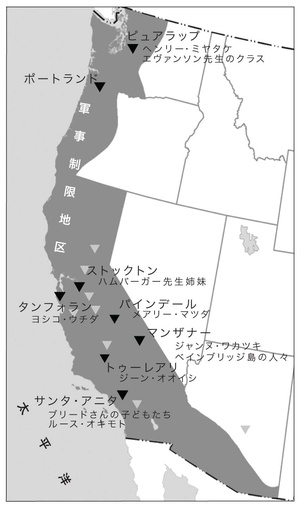

While waiting for the completion of the inland internment camps2, Japanese Americans were gathered in "assembly centers." There were 13 in California, and 16 others in Portland, Oregon, Puyallup, Washington, and Mayer, Arizona. Horse racetracks, livestock exhibitions, and state fairgrounds3 were used as makeshift housing, and Japanese Americans spent an average of 100 days in these temporary camps. The U.S. Army and the War Civilian Administration (WCCA) were in charge of administration, but activities within the camps were left to the Japanese Americans themselves. The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) acted as an intermediary between the administration and the internees.4

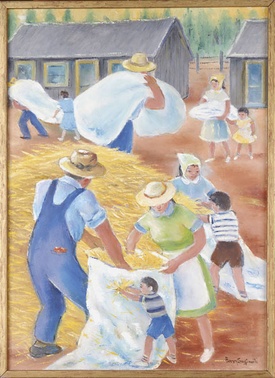

There was no sewer system, only one bare light bulb hanging from the ceiling, and one stove and one electrical outlet in the middle of the room. This was the setup of each room provided by the military, and it was the same in every camp. The equipment consisted of military cots, military blankets, and cloth bags for mattresses. We stuffed straw into the bags ourselves to make mattresses. The walls between adjacent rooms did not reach the roof of the barracks, which had no ceiling, so everyone could hear each other. The dining room, laundry room, toilets, and showers were all shared, and the toilets and showers had no partitions or doors. Modest people would think that they would go late at night when there were fewer people around, but when we went there, we found that there were others who thought the same. This was the beginning of a life without even a little privacy.

When the Japanese arrived at the hastily constructed internment camps, everything was only half-done, from the construction of barracks to the preparation of sewers. How did they build their lives and communities in such chaotic circumstances? How did they "lead the children to creative and constructive lives"? As we explore this through the eyes of the children, we see the presence of people both inside and outside the camp who lent a helping hand, doing what they could, at their own responsibility.

1. Children's "gathering place"

Soon after being detained, the children began writing letters. The first was a letter from the Puyallup detention center to Mr. Evenson and his class at Washington Middle School.

...We have to make our own chairs, tables, and mattresses for our beds with straw. (Isn't that terrible?)... P.S. Please write to me. And to all the other students in my class. It's lonely here. Could you please send me a photo of the teacher? 5

Mary

The children, who had been seen off by Clara Breed at the Santa Fe Station in San Diego, arrived at the Santa Anita Asylum in California. Babe Kasahara entered her new room for the first time.

...We lived in a horse stable. There was dried horse manure in the cracks in the asphalt. My mother had tears in her eyes and said she wouldn't go in there. ... My father wasn't with us because he was taken in by the FBI. He was held in Santa Fe, New Mexico for five months, and when he heard we were going to be evicted from San Diego he wrote in his diary, "Everyone is worried about being evicted. My eyes are full of tears. I can't believe this is happening in the country of the free!"

Luckily, our neighbor from Los Angeles lent us a broom and bucket, so we splashed water on the asphalt and scrubbed it clean. Then my mother said she wanted to go inside. But the awful smell lingered for a long time. The walls were sprayed with smudge paint, and probably had horse manure mixed in with the straw. 6

Jeanne Wakatsuki arrived at the Manzanar temporary camp on Terminal Island, located at an altitude of 1,200 meters above sea level, about 330 kilometers inland from Los Angeles. The cold winds blowing down from the Sierra Nevada mountains were whipping up the desert sand and creating a sandstorm. Even Jeanne was surprised by this sandstorm.

We rode the bus all day. When we arrived at our destination, the shades were up. It was late afternoon. The first thing I saw was a yellow swirl that blurred the red of the sunset. The bus was making a noise like a torrential downpour, but it wasn't rain. It was my first glimpse of what would soon become familiar: a dust storm blowing in from Owens Canyon.

We woke up early the next morning, shivering and covered in dust that had blown in through holes and cracks in the door. During the night, Mom had pulled out all our clothes and piled them on our beds so we'd sleep warmer. Our room looked like a big dry cleaning bag had burst open, blowing a fine dust over the clothes. The floor was covered in a thin layer of sand. I looked over Mom's shoulder to see Kiyo, who was on the edge of the fluffy mattress, buried in his jeans, overcoat and sweater.

Kiyo had white eyebrows. He started to giggle. He was looking at my white eyebrows and hair. Soon we were both giggling. I looked at Mama's face to see if she thought Kiyo was funny, but she lay motionless next to me. Her eyes wandered slowly over the bare rafters, the walls, the dusty children, over everything. If Woody hadn't called out to her through the wall at that exact moment, Mama's frozen face would have broken and she would have burst into tears. 7

After the Wakatsuki family's father was taken away by the FBI, 24-year-old Woody, the elder brother, played the role of father. Woody found empty can lids and nails from somewhere and hammered them into knot holes and cracks in the wood to plug the holes. At that time, the sound of hammering nails echoed everywhere in the temporary camps from Washington to Arizona. He made tables, chairs, and shelves from scrap wood left over after building barracks and nails scattered around.

Library Play

As long as they have loving family and friends, children have the ability to survive anywhere. They can also invent games. Breed and the children continue to correspond, and she continues to send them letters and books for review sent by publishers and books to be discarded by libraries, along with small items such as candy and bubble gum. On a spring day when the fresh breeze rustled the palm leaves, Elizabeth, who was in the Santa Anita temporary camp, was making homemade library cards to start a pretend library with her sister Anna and nearby friends. She remembered the library in San Diego where Breed was. From Elizabeth's letter dated April 25th:

Thank you for your letter and the books. It made me very happy. Yesterday, I collected 10 books to make a library. The books are "The Wizard of Oz", "Carmen of the Gold Coast", "A Mother's Prayer", "The Bible Stories", "Rebecca", "Wuthering Heights", "The Christ Child", and the three books you sent me. The library will open on Monday. I made two cards for each book. I will put one on the envelope and the other on the book cover. Playing in the library is a lot of fun. Soon we will have a big library here too. I have already read the books you gave me, but I will read them again. I have made library rules with my friends. 8

Notes:

1. Letter by Andrew Kuroda, May 6, 1942, Folder 16, Box 4, Gov. Sprague Records, OSA.

2. About distorted expressions: Until the long-term internment camps were built, the government and the Army called the places where Japanese Americans were forcibly taken "Assembly Centers." Manzanar was called the "Reception Center." What do you think of when you hear the words "Assembly Center" or "Reception Center"? The Army's propaganda department even came up with the name "Camp Harmony" for the Puyallup "Assembly Center." Isn't Camp Harmony a fun place where kids go to play in their sleeping bags in the summer? These are expressions that the government and the Army came up with to distort the facts. In reality, as Gene said, "anyone could see it as nothing but a POW camp." So when writing or talking about those days, the question is whether to use the terms that were actually used at the time or terms that more accurately describe what was going on there. In the main text, distorted terms are used in quotation marks. Nisei people often use the word "camp" for both "assembly center" and "relocation address."

3. The state fair, held once a year for the citizens of the state, started as an agricultural product fair, but in the 20th century, it was equipped with amusement park rides and concert venues, and carnival elements were added. During the war, the military saw the state fair as a relatively large place with well-developed infrastructure, making it convenient for building temporary camps. So in Puyallup, barracks were lined up next to the roller coaster.

4. However, even before the forced eviction, the JACL had consistently maintained the stance that "following completely what the government says would show Japanese Americans' loyalty to America," which later led to backlash from the first generation and second generation Japanese who had returned to America.

5. Letter by Mary Hashimoto, May 10, 1942. Ella C. Evanson Scrapbook. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

6. Joanne Oppenheim, translated by Ryo Imamura, "Dear Breed" Kashiwa Shobo, 2008

7. Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston, translated by Kwon Yasushi, "Farewell to Manzanar: A Record of the Heart of a Japanese-American Girl Interned in the United States," Gendaishi Shuppansha, 1975.

8. "Dear Breed" (ibid.)

*Reprinted from the 134th issue (July 2013) of “Children and Books,” a quarterly magazine published by the Children’s Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett