Read Chapter 2 (2) >>

2. Start from what you can do and within your reach

The adults around the children begin to do what they can, wherever they notice something or where there is a need. Even in this environment, the way they take the initiative to try to make it as livable as possible shows the indomitable and positive energy of the Issei and Nisei. It is spring, and it is in tune with the rhythm of nature. This is how the founding of the library also began, but we'll talk about that a little later. Here are two examples from rainy Puyallup.

Jim Akuts was working in the cafeteria. One day, he noticed someone wrapping up leftover bread on a plate. Hearing this, he learned that he was taking it home to his mother, who was sick and couldn't come. Hearing this, Jim realized, "That's right, it must be hard for elderly and sick people to walk to the cafeteria and then wait in line outside for hours," so he started a tray service to deliver meals to such people. This service soon expanded to hospitals and isolation wards. Jim says, "We just did it because there was a need." 1

Whenever it rained, the roads turned into a muddy mess that made it hard to walk. There was no paved ground anywhere in the camp. In her autobiography, Monica Soné described the place as "an ocean of man-eating mud." 2 The camp newspaper even joked that if you went to the shower in normal shoes, you would need angel wings to come back. This is when Toyonosuke Fujikado, a member of the Issei family, came into the spotlight. He turned a corner of his barracks into a mini geta workshop, using scrap wood and accepting no money, and making over 700 pairs of custom-made geta in all different sizes, shapes and heights, just as people asked. 3

Because these were temporary internment camps for a short period of time, the Wartime Civilian Administration did not think about school or how the internees would spend their leisure time. However, having nothing to do all day was boring, and a decline in morale became an issue. So they quickly created education and recreation departments in each internment camp, with the Japanese interned people in charge of actual planning and operation. The education department quickly drew up plans for schools and nursery schools, and began recruiting teachers. In the recreation department, activities quickly began, ranging from baseball, basketball, softball, and sumo to knitting, crafts, go and shogi.

3. School

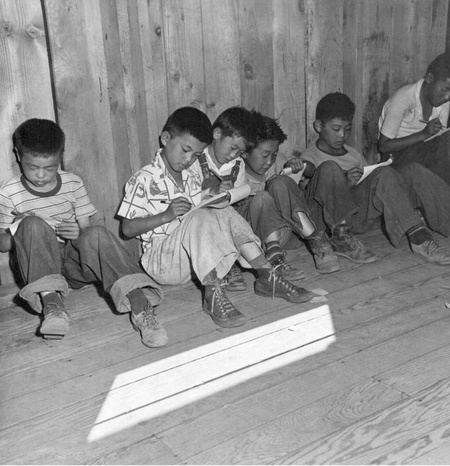

The school started before there were even desks or textbooks. The photo in this issue was taken when a second generation college student volunteered as a teacher at Manzanar and started the school to teach discipline to the children. There is nothing there, but the natural light coming in through the window reflects on the neatly swept classroom floor, giving a refreshing impression, doesn't it? There are people who care about the children, there are children who want to learn, there is a space where they can learn, and there is a trail of light that changes from moment to moment. It seems that time flows contentedly here alone. The photo was taken on July 1st by government photographer Dorothea Lange.

At the Tanforan camp, Yoshiko Uchida's sister Keiko was put in charge of setting up a nursery school. Keiko had studied child development at Mills College and was qualified as a nursery teacher. However, even after graduating, she was unable to find a job that would utilize her qualifications. Keiko was not the only Nisei to have experienced the same thing. There were no jobs due to racial prejudice. It was a time when graduates who had studied aeronautical engineering at university sold vegetables. Do you know the architect Minoru Yamasaki? He is one of America's leading architects of the 20th century, and designed the World Trade Center in New York. He studied architecture at the University of Washington, but was unemployed at the time of graduation, so he worked as a helper in a store and sometimes delivered to Henry's father's store. Fortunately, he was able to work at an architectural firm in New York before the forced eviction began, and was spared from eviction. At the camp, Keiko was given the opportunity to do the job she was meant to do for the first time. Later, Yoshiko became an elementary school teacher in the camp, but before that she helped out a little at Keiko's nursery school. It's a fascinating episode from that time.

...Whenever children played house, instead of cooking and setting the table as they did at home, they would queue up to eat in an imaginary restaurant. It was sad to see how quickly a child's idea of home had changed. [4]

The teacher who brings the salami and the school

"A single candle illuminating the darkness is better than a hundred candles in the daytime. For many Japanese Americans, the kindness they received during the internment camps and wartime, no matter how big or small it was, rekindled the flame of hope that had almost died out, and reaffirmed to them, in the darkest hours of their lives, that human beings are worthy of love and trust. That flame continues to burn today," is what I found in a book of memorable stories recommended by former internees.

Elizabeth and Katherine Hamburger, both teachers at Stockton High School during the day, went to Stockton detention center every night. Since they did this almost every night, they were familiar with the soldier guarding the gate. The guard probably thought that the two women were either pregnant or very overweight. In fact, they had wrapped around their stomachs salami and other prohibited foods that had been given to them.

The Japanese-American students at Stockton High School were sent to the internment camp one month before the end of the semester, and if things continued as they were, they would not be able to earn credits for that semester and would not be able to move up to the next grade. So the sisters came up with the idea: "If the government is going to take the students away from the school, then let's take the school to the students." They planned to have university students who were also being held in the internment camp as teachers, have the students from Stockton High School tutor them, and get the school authorities to recognize their credits. They would go to the internment camp almost every night to teach the university students who had suddenly become teachers how to teach, or to hand out the handouts that other teachers from Stockton High School had handed out in class that day. 5

Graduation Ceremony

A solo graduation ceremony

My diploma, rolled up and placed in a cardboard tube, was delivered to my cabin by the postman from Tanforan camp .

This was Yoshiko's only graduation, as she was deprived of the opportunity to attend the University of California, Berkeley graduation ceremony by two weeks.

Thirteen empty chairs

Let Mary Woodward continue with her baseball game story as she gives us two Bainbridge High School graduation ceremonies.

... There were 13 Japanese students who were supposed to graduate with the rest of the class, a quarter of the graduating class. Yes, a quarter. They were all student leaders, stars on the basketball team, leaders of the student council... There were many outstanding students who were fully integrated into Bainbridge High School. ... The school may have been lenient in some subjects given the circumstances, but once they were sure that the 13 students had completed the studies required for graduation, they sent them to Manzanar to be handed their diplomas, along with the drafts of speeches to be read at the graduation by the chairman of the board of education and Principal Dennis. So we were able to hold the Bainbridge High School graduation ceremony at Manzanar, and at the island's graduation ceremony, 13 empty chairs were lined up on the podium. 7

Notes:

1. Jim Akutsu, interview by Art Hansen, June 9 & 12, 1997, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

When Jim first started tray service, he went to get permission from the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), which oversees daily activities within the camp, but the JACL ignored him, presumably because they had too many issues they needed to resolve at the time. Jim thought, "Feeding the elderly and sick is important. We need to get started right away," so he got permission from the camp director over the head of the JACL, and started recruiting volunteer high school students.

2. Sone, Monica. Nisei Daughter. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1953.

Monica herself had a pair of red geta made. She begged her father, who, through a friend of a friend of her father, asked a carpenter to make geta. It was probably Fujikado. Monica revealed, "The geta can be worn in the shower, they're three inches high so they're fine in mud, and most importantly, they don't require stockings, so they're a lifesaver."

3. Camp Harmony News-Letter, June 17, 1942.

4. Yoshiko Uchida, translated by Kazuo Hatano, "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of a Japanese-American Family During the War," Iwanami Shoten, 1985

About a week after Yoshiko and her family arrived at the temporary camp, her father, who had been held by the FBI, was paroled and they were able to live together. Yoshiko attributes three reasons for her father's relatively early parole to the fact that he had retired from Mitsui & Co. two years before the war began, his volunteer work in the community, and the effectiveness of sworn testimonials from acquaintances about her father's personality and actions.

5. Seigel, Shizue. In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment . San Mateo: AACP, Inc., 2006.

6. See above, "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of a Japanese-American Family During Wartime."

7. Mary Woodward, interview by Debra Gindeland, 8/3/2007, Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community Collection, Densho.

*Reprinted from the 134th issue (July 2013) of “Children and Books,” a quarterly magazine published by the Children’s Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett