I thought it was very unfair of my parents to make me go to Saturday School to learn Japanese. All the other kids I knew from public school got to take the whole weekend off, but not me—I had to go to Saturday School from 9 in the morning ‘til 3 in the afternoon to learn what seemed to be the most boring subject in the entire world—Japanese.

My Issei parents thought it was important that their American-born children study Japanese and learn a little bit of the Japanese culture. The lack of a common language was a barrier to having any real communication between me and my parents. My Japanese language skills were pretty limited to things like “when do we eat?” and “you are a baka.” So my parents made me go to Saturday School to learn Japanese from the time I was six years old. I thought since we were living in America, it should be my parents’ obligation to learn English, but even after decades of living in this country, English was still a foreign language to them. And so we were sent to Saturday School to learn Japanese.

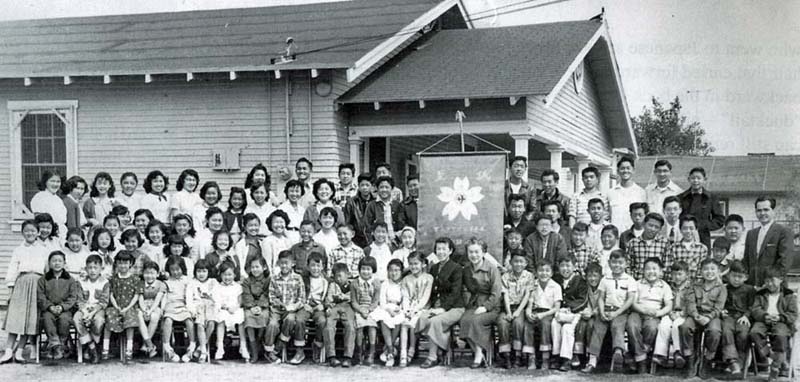

This was the lot for about 150 of us Japanese American kids back in the 1950s, growing up in the San Fernando Valley. For nearly 10 of the years that I attended Saturday School, I sat next to Dick who became my best Japanese school friend. We often commiserated about our plight and came to the conclusion that we must have earned some serious bachi when we were very young. Bachi is a Japanese term that is similar to something like “karma”—the idea that you must have done something bad to have earned a subsequent calamity in your life. Thus, the punishment of having to go Saturday School must have been bachi—some evil thing we had committed as children or perhaps in another life. Dick and I used to wonder what major misdeed or terrible evil we could have possibly done in our short young lives to have merited such bachi. Dick and I concluded that the main reason we stuck it out at Japanese School was because if we refused to go to Saturday School, we feared that our parents would disown us and we would get nothing to eat. This was what it boiled down to—we endured Saturday School because we wanted to ensure our next meal.

The teachers at Saturday School were mostly amateurs—folks from Japan who needed the money or who had nothing better to do on a Saturday. The teachers tried to teach us the Japanese alphabet and then kanji (Chinese characters), but we tried to get away with doing as little as possible, and not surprising, only a small amount of knowledge actually sank into our inattentive young brains. While the teachers were giving their Japanese lessons, we sought to find ways to pass the time. When the teacher wasn’t looking, we would exchange dozens of silly notes about trivia that were written on small sheets of paper and folded into tiny squares and then secretly passed from student to student. Entire games of “Hangman” could be played surreptitiously while the teacher stood in front of the classroom droning on about “sa-shi-su-se-so” (a line in the Japanese syllabary). I had no clue at the time what importance there could ever be in learning “sa-shi-su-se so.”

The principal was Mrs. Yamaguchi, a short but stern teacher, and everyone, and I mean everyone, knew she was the boss. When she scolded someone, even the toughest kids would toe the line because Mrs. Yamaguchi always carried herself with the air of a leader and a strong personality and no one messed with her. She could, almost like God, just walk into a noisy classroom and instantly, the room would turn quiet. Even though she scared me, I had to admire the power she held over us all. Even though she was pretty old, and when you are only about ten years old, most adults look pretty old, I always thought that she must have been beautiful when she was younger.

We looked forward to recess and lunch breaks when we could go out and play or eat snacks. Though I can’t remember the lessons that were taught, the amazing thing is I can vividly remember what we did during breaks. During lunch breaks, we would play indoor games such as cards, look at school year books, take surveys of who was the “coolest looking guy or girl,” and we would also play outdoor games like basketball or even football on a tiny playground of asphalt. Sometimes, we would walk down to the local Mexican-owned grocery store and buy a giant dill-pickle for 5 cents and munch on it ‘til the break ended. We used to talk endlessly about a new song or a new singer, a new movie, or which local school had the best basketball team.

We were all equals at Japanese School, that is, there were no pretensions, no cliques, and no elites. The older kids didn’t look down on the younger kids as if they were stupid punks. This may be because deep down inside, we subconsciously knew we were all inmates of the same institution. Among our ranks, were student body presidents, valedictorians, salutatorians, Ephebians (California Scholarship Federation Seal-bearers), but in Saturday School, we were all on the same footing—we were trapped and had to make the best of it.

There were also some borderline delinquents who went to Japanese school; these guys had hair that curled forward in the front and combed backward in the back in what was called a “ducktail”—picture a Nikkei Grease cast. I can still remember one fellow I shall call “Stan” who some might consider a bully. Stan was big, and worked out with weights, and had a reputation as a ferocious fighter. I never saw Stan in a fight, but my friend Dick did. Dick gave a detailed description of how he saw Stan pummel a Mexican kid at junior high school and that was good enough for me—I tried to stay on Stan’s good side as best I could. One time at Japanese School, Stan was talking to me about a dance he went to at high school, and how one of his Mexican buddies got high on marijuana or something and how this guy was giggling in a high-pitched voice and then Stan said the guy suddenly pulled out a zip-gun and stuck it under Stan’s chin. At this point, Stan decided he wanted to enact the scene with me, perhaps so I would get the full flavor of the story, so Stan started to giggle in a high-pitched voice, and he grabbed me by my neck and used his closed fist to pretend he had a gun under my chin. While Stan was subjecting me to this bizarre behavior, all I could think of Dick’s descriptive story of Stan pummeling this other guy senseless, so I forced a smile, hoping Stan’s story had a quick and happy ending. Stan held my face about two inches away from his face, just above his closed fist which sat atop a muscular forearm, for about 15 long quiet seconds. Suddenly, Stan said his friend in the story started laughing again and put the zip-gun away, so that is what Stan did. He pulled down his fist and walked away, laughing. I was a little weak in my knees for a few moments, and then decided to take a breath, and be grateful nothing happened to me. For the most part though, Stan was just another inmate and we got along without major incidents.

The irony of all this is that Saturday School has, in many ways, left a greater mark in my life than public school itself. Dick and I have remained close friends for over 50 years, and whenever I see another J-school classmate, there is always a bond of friendship and empathy that is shared at a deeper level than other relationships.

Another irony is that my mother always told me that someday I would be glad she made me go the Japanese School and when that day came, I would regret not having studied harder. And sure enough, doggone it, she was right. That time came when I graduated college and realized that I still couldn’t communicate with my parents beyond grunts and asking in basic Japanese, “When do we eat?” My Japanese proficiency must have been a major disappointment to my parents after all the money spent in paying for Japanese school but they never said anything or criticized me.

I ended up going to Waseda University in Japan for one year to try to improve my simple Japanese so I could speak in real sentences and have more of a human vocabulary. After returning home, I found I could actually carry on a conversation with my parents on subjects more profound than just “what’s for dinner?”

It felt great to be able to communicate with my parents and to talk with them like parents and children should. I realized how much I had missed all those years I chose to remain monolingual English. I like to think that my parents were happy that I chose to go to Japan, and that perhaps all those Saturday lessons weren’t totally wasted. My mother was right about making me go to Saturday School, but not because it helped me learn Japanese, but because of the recess and lunch breaks and friendships that helped make me the person I am.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices: The Japanese American Family, in September 2010. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2010 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California