Read the prologue >>

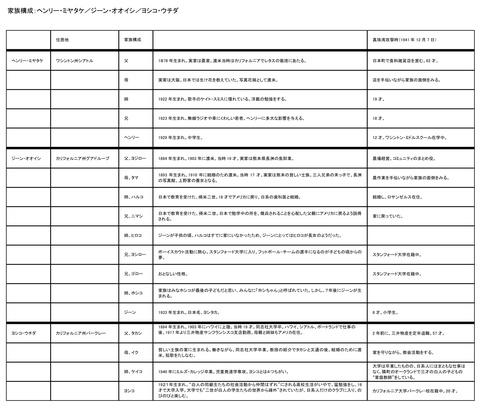

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, more than 110,000 Japanese people living on the West Coast of the United States were sent to internment camps. Two-thirds of them were born in the United States and were citizens, but they were simply of Japanese descent. Why did such an injustice happen, despite the United States Constitution, which proclaims individual freedom and equality?

1. Historical Background

Immigration from Japan to America began with immigration to Hawaii in 1885, and reached its peak from the 1890s to 1924. With the tax reforms following the Meiji Restoration, taxes were no longer collected on a village basis as in the Edo period, but were instead collected by individuals in cash, and farmers without cash had to borrow money from loan sharks using their land as collateral to pay their taxes.

So the second and third sons of farm families who were forced to live in poverty came to America in hopes of getting rich quick. But that's not all. Many immigrants also came to America in search of a new place to work, such as Asano Shichinosuke, a freedom and civil rights activist in the mid-Meiji period and a student of Hara Takashi.

Gene Oishi later wrote his autobiography, Torn Identity: The Life of a Japanese-American Journalist (translated by Someya Seiichiro), in which he tells the following story.

Gene's father was born in Nagasu, which faces the Ariake Sea in Kumamoto Prefecture. His grandfather was a fish wholesaler there. Apparently, whales used to come to the bay when his father was a child. However, as the fish stocks decreased, the whales stopped coming, and his grandfather's work also decreased dramatically. He also failed in an investment he had made to save the store, and he ended up with a large amount of debt. So his father, the second son, came to America at the age of 19 to pay off his grandfather's debts. He arrived in San Francisco in 1903. His goal was to work for a few years, save up money, and return to Japan. Although he had studied English for two years in Kumamoto, he had no one to rely on.

When he first arrived, he worked as a restaurant helper and in an orchard, but a year later he moved to Guadeloupe in the Santa Maria Valley, where he quickly rose to prominence. When it was discovered that his father was Japanese and could speak a little English, he was asked to bring in many Japanese workers to a sugar beet plantation, and he was hired as a supervisor. Until then, the majority of the workers on the plantation had been Chinese, but they were getting older, and since it was the time of the Chinese immigration ban, no new immigrants were coming, and the plantation was in trouble. By the seventh year after arriving in San Francisco, he was able to own his own plantation. "The fact that he had finally paid off this debt was a source of pride for my father. He would often tell me that my grandfather could once again walk the streets of Cheung Chau with his head held high," Jean writes. 1

Around the time Jean's father moved to Guadeloupe, anti-immigration movements from Japan began to grow. Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War stirred up fears of a Japanese invasion of the American West Coast, economic considerations caused by fears that an increase in hardworking, low-wage Japanese would become competition for jobs, racial prejudice that called for the Japanese to be expelled from California, and politicians' intentions to use these movements to their own advantage... 2

The first generation of Japanese on the West Coast, especially in California, 3 endured hard labor every day amid a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment, but in those days when everyone was poor, Japanese people lived by helping each other. Even in those difficult times, they raised their children well, and the children learned the Japanese values of hard work, honesty, and perseverance from their parents.

Library usage status

Nisei children had free access to public libraries, and Issei parents encouraged their children to attend libraries as well, as they believed education was very important and wanted their children to surpass their parents.

Japanese-American children are avid readers and have good manners, so they are also loved by librarians. Seattle librarians also praised them, calling them "one of the best groups of users this library has had since it was established." 4 Natalie Mayo, librarian at the San Francisco Central Library's Children's Room, also wrote in a letter that "The (Japanese-American) children follow the library rules and consider it a great privilege to be able to borrow books and take them home. I hope that American children can learn these things from Japanese-American children, who are foreigners." 5

At that time, school libraries were run by public libraries, so public librarians delivered books to schools. In those days, there was a record of a happy exchange between a librarian and children that is not seen in libraries today. ("Dear Mr. Breed" by Joanne Oppenheim, translated by Ryo Imamura)

Many Nisei children loved going to the San Diego Public Library Downtown Branch, which was within walking distance from their homes, not only for the books but also for meeting "Mr. Breed," who had been by the children's side for 14 years, handing them books.

There must have been a relationship of trust between Breed and the children. It seems that the children told Breed everything. Breed responded to them and faced each one honestly. The children who attended Breed's school are "Mr. Breed's children." Tetsuzo and Louise say the following:

Mr. Breed introduced me to the fascinating world of books. ... Ironically, it was probably a good thing that I didn't have parents to look after me. My mother died when I was five years old, and my father worked 16-hour days. I was told strictly to stay away from trouble and live an honest life, which is one of the reasons I became a bookworm. I read everything I could find, from one end of the library shelves to the other. When summer ended and school started, I would go to the school library, and when summer vacation came, I would go back to the town library. All the while, Mr. Breed gently and gently guided me. 6

Railroad elephant

I think I started reading when I was about eight years old. It was all thanks to the summer reading club that Ms. Breed started at the children's library. She was very kind and helpful, and always greeted us with a happy smile. Thanks to the reading club, we were able to spend busy and fulfilling days throughout the summer vacation. She prepared many different programs for us, one of which was to travel the world through reading. She made a map and prepared books for us from various countries. When we joined the reading club, we were each given a number. Then, when we finished a book, she would put a star with our number written on it above the country that we had. In this way, she made our summers fun and not boring, and she made us love reading. 7

Louise

Yoshiko Uchida, who lives in Berkeley, also enjoyed going to the library. In a book she wrote before completing her autobiography, "People Driven to the Wilderness: A Record of a Japanese-American Family During Wartime," she wrote about her favorite books as a child.

I loved going to the South Berkeley branch of the library. I always headed straight for the children's books. The first thing I did was look for the ones with a star on the spine. They were my favorite mysteries. I read a lot of books like "The Mystery of the Old Violin" by Augusta H. Seaman. I also liked Hugh Lofting's "Doctor Dolittle" series and Louisa May Alcott's "Little Women" and "Little Women No. 3". Other books I liked were Anna Sewell's "The Black Horse" and Frances Hodgson Burnett's "The Secret Garden". ... I couldn't read Japanese myself, but I loved having my mother tell me stories like "The Old Man Who Made Flowers Bloom" and "The Tongue-Cut Sparrow" before I went to bed at night, and singing nursery rhymes to me. 8

Libraries and the First Generation

But for Issei parents, public libraries were not exactly a welcoming place. Very few people could read English, and there were almost no books in Japanese. For many librarians, the Issei were invisible, or rather, they did not want to see them.

Andrew Wertheimer introduces this anecdote in his research on community libraries in Japanese American internment camps. It is a letter from the San Francisco Public Library in 1919, during the post-World War I recession, requesting assistance from the Japanese Consulate General when they stopped accepting subscriptions to Japanese-language newspapers. "If you could donate Japanese-language newspapers, they would be appreciated by the Japanese residents staying temporarily for work or vacation," the letter says, but makes no mention of the 5,358 Issei who lived in the city at the time. 9

Notes:

1. Gene Oishi, translated by Someya Seiichiro, "Torn Identity: The Life of a Japanese Journalist," Iwanami Shoten, 1989

2. In May 1905, representatives of 67 organizations gathered in San Francisco and would later launch the Anti-Japanese League. In 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education announced that it would segregate Japanese children from regular schools to existing schools for Asians only. President Roosevelt, who learned of this policy through a report from Tokyo, was troubled and expressed his intention to work with the Japanese government to resolve the situation. The conditions were that California would stop segregating Japanese children and would not make any further regulations that discriminated against Japanese people. As a result, a gentlemen's agreement was concluded between Japan and the United States, and the Japanese government would voluntarily refrain from issuing passports to workers in the United States.

There was a big difference between immigrants from Europe and immigrants from Asia. European immigrants were able to become naturalized and obtain citizenship, but this path was closed to Japanese and Chinese immigrants. The 1913 California Alien Land Law (First Japanese Exclusion Land Law) prohibited Issei Japanese from buying land or renting land for more than three years. It was too cruel to have to change farmland every three years and start from scratch when farming. However, in dire straits, there were many cases where Issei parents were able to get away with it by buying land in the name of a citizen Nisei and registering them as guardians. However, in 1920, the Second Japanese Exclusion Land Law was passed, which made the 1913 law even stricter. This time, it was completely prohibited to sell or rent land to those with Japanese nationality. Issei could no longer be guardians of minor children when buying or selling land.

3. Because the Issei were not able to obtain American citizenship, they are technically Japanese, but in the text they are referred to as Japanese-Americans along with the Nisei.

4. Becker, Patti Clayton. Up the Hill of Opportunity: American Public Libraries and ALA During World War II . [Doctoral dissertation] Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002.

5. Tayler, Zada. War Children on the Pacific: A Symposium Article, Library Journal. Vol. 67, June 15, 1942. American Library

Association (ALA) Archives. It is unfortunate that even the librarian Mayo did not realize that Japanese-American children born in America were American, even though they were foreigners. It's just that their faces look different.

6. Hirasaki, Tetsuzo. In Memory of Clara Breed , Footprints, newsletter of the Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego, 3:4 Sinter 1994. Joanne Oppenheim, translated by Imamura Ryo, Dear Breed, Kashiwa Shobo 2008

7. Joanne Oppenheim interview with Louise Ogawa

8. Uchida, Yoshiko. The Invisible Thread. New York: Julian Messner, 1991.

9. Wertheimer, Andrew B. Japanese American Community Libraries in America's Concentration Camps, 1942 – 1946. [Doctoral dissertation] Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2004.

*Reprinted from the 133rd issue (April 2013) of "Children and Books," a quarterly magazine published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett