Read Chapter 1 (3) >>

4. Eviction Order <Spring 1942>

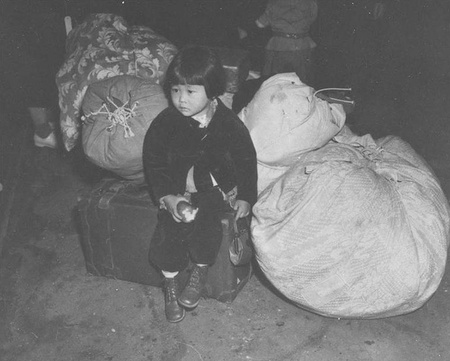

Finally, the evacuation of Japanese Americans from military areas designated on the West Coast began. Some families voluntarily moved from the military areas, but this was a massive migration of more than 110,000 people. The construction of permanent inland relocation camps was not completed in time, so people set off to temporary "assembly centers." The evacuation began from the areas most inconvenient to the military.

(Photo: National Archives and Records Administration)

Bainbridge Island, with its nearby naval base, was the first to receive an eviction order on March 24th. Bainbridge Island is a 30-minute ferry ride west of Seattle, and at the time, about 250 Japanese people lived there, mainly working in agriculture and fishing. They were instructed to take only what they could carry with them: bedding, toiletries, clothing, knives, forks, spoons, bowls and cups for eating. Shortwave radios and cameras were prohibited items. Departure was scheduled for Monday, March 30th, at 11:00 a.m., so there was less than a week to prepare.

Preparations began, with people selling, renting or depositing farmland, trucks, farm tools, houses, furniture, clothes, kitchen utensils, etc. Preparation periods varied from place to place, but at most it was a few weeks. The shortest was in Terminal Island, California, where an eviction order was issued on February 25th. The time given was 48 hours. That's right, just two days.

Jeanne Wakatsuki's family was there. After her father was taken away by federal agents, the family moved to Terminal Island with her siblings. "For several weeks, second-hand dealers had been roaming the area like wolves, offering extremely low prices for furniture and other items that we would sooner or later have to sell," she wrote in her book "Farewell to Manzanar: A Record of the Heart of a Japanese Girl Interned" (translated by Gon Yasushi). Jeanne, who was seven years old at the time, vividly remembers the morning of her departure, when she was unable to take with her mother's "fine, almost transparent, old blue and white porcelain set."

A salesman offered $15 for it. Mom said it was a set of 12 and would be worth at least $200. The man said $15 was the best he could get. Mom began to tremble and glared at the man. Mom was in hysterics after spending the whole night packing and trying to calm Grandma, who didn't understand why we were moving again and why we were so busy working. Navy jeeps were patrolling the streets now. Mom said nothing more, just glared at the man. Anger and frustration were shining through Mom's eyes.

The man stared at her for a while and then said he couldn't pay more than $17.50, at which point she reached into a red velvet box, pulled out a plate, and threw it at the man's feet.

The man jumped back and cried.

"Hey, hey, don't do that! It's a valuable plate!"

Mama didn't move, just shuddered with her mouth closed, glared at the retreating man, and took out more plates, throwing them, one by one, to the floor, tears streaming down her cheeks.... After the merchant had gone, Mama stood there, smashing cups and bowls and plates, until the whole china set lay in blue and white shards on the floor. 1

Henry's father's grocery store had just been renovated the previous year, with refrigerators, cabinets, etc., at a cost of $ 9,000 , but how much do you think the store and inventory cost? All told, it was only $400.

Some Buddhist churches and churches were willing to store luggage for them. Breed's house wasn't big either, but he stored the children's important belongings for them. What do you think Tetsuzo left behind?

I had kept my own little library of math, science, language, and other study guides, as well as other books, in a small apple box, but since I couldn't take them with me, Mr. Breed took care of my "library. " He kept the sealed box for me until I returned to San Diego.

At school, Henry was told not to talk about the internment camps. But his new friends seemed to know about it. During homeroom, when the teacher said, "Tomorrow is the last day for some of you," Henry suddenly stood up and began to speak: "I never came to America to see this happen. I don't know what's going on, but this is not what I came here for." 4

In Mr. Evenson's class at the same junior high school as Henry, Japanese-American children wrote down their feelings at the time in a signing book.

… I don’t want to leave Seattle because I won’t be able to see my friends, teachers, or my school. But there’s nothing I, or any of us, can do about it. …

Eye 5

…Even if I have to leave Seattle, I can’t go back there anytime soon because I was born here. But I will never forget the teachers at my elementary school and Washington Middle School. They were all very kind and taught me a lot. I hope to meet good teachers like the ones in Seattle in the future. I am an American.

Haruo 6

…I am sad about being evicted. I will miss my studies and my teachers, friends, and Principal Sears. Maybe it would be better for me to go to an internment camp, as the government says. But I hope there will be a school so I can continue my studies. As you know, Seattle is my hometown, so I am sad to leave. I hope the war ends soon so I can come back here and attend Washington Middle School, which I love. …

Kazuko 7

5. A journey without a clear destination <Spring to early summer 1942>

Bainbridge Island Ferry Pier

There were also six players on the pier who had fond memories of fun games. Mary Woodward recalled one baseball game that took place four days before the eviction:

The evacuation order was sent to all Japanese residents of Bainbridge by March 30th, and it was on the 24th, so I think it was the 26th. There was a baseball game between Bainbridge High School and North Kitsap High School, a strong rival from the neighboring town. It was an important game to open the season. The team had a strong-willed player, Earl Hansen, but the coach, Walter Miller, who everyone called "Dad Miller", put all the Japanese players on the field and did not make any substitutions during the game. There were six of them, although some of them always sat on the bench.

The result was a disastrous 15-0 result.

Mary's father, newspaper reporter Walt Woodward , was also at the game.

After the game, the disappointed catcher, still wearing his heavy gear, was trudging down the hallway to the locker room when a blonde female student appeared from somewhere, caught up with him, quietly put her arms around his sweaty gear, kissed him, and ran off crying. I happened to see this and realized that it wasn't just Japanese people who were sad.

(Photo: Dorothea Lange, National Archives and Records Administration, Densho ID: denshopd-i37-00436)

Santa Fe Station

On April 7th, Clara Breed, a librarian in charge of the children's section at the San Diego Public Library, was seen searching for children who had come to the library in a building crowded with Japanese Americans who were to be deported. She handed each child a postcard with a one-cent stamp and their address on it, encouraging the children who didn't know where they were going or how long it would take to return, saying, "Write me a letter. Let me know how the camp is going. I'll send you a book. " 11

Notes:

1. Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston, translated by Gon Yasushi, "Goodbye Manzanar: A Record of the Heart of a Japanese-American Girl Who Was Incarcerated," Gendaishi Publishing, 1975

2. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

3. "Dear Breed" (see above)

4. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

5. Scrapbook Entry, dated April 17, 1942. Ella C. Evanson Scrapbook. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

Pak, Yoon K. Wherever I go, I will always be a loyal American: Schooling Seattle's Japanese Americans during World War II. New York: RoutledgeFalmer, 2002

6. Scrapbook Entry, dated March 25, 1942. Ella C. Evanson Scrapbook. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

Pak, Yoon K. Wherever I go, I will always be a loyal American: Schooling Seattle's Japanese Americans during World War II. New York: RoutledgeFalmer, 2002

7. Scrapbook Entry, dated March 23, 1942. Ella C. Evanson Scrapbook. University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

8. Mary Woodward, interview by Debra Grindeland, August 3, 2007, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

Seigel, Shizue. In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment . San Mateo: AACP, Inc., 2006.

Paul Otaki, a former Bainbridge High School student, said, "Coach Miller didn't care about the score in that game, he just wanted the Japanese players to have fun playing in their last game at Bainbridge High School. We lost 15-2, but I will never forget Father Miller's kindness."

9. Walt and his wife Millie Woodward published the Bainbridge Review on Bainbridge Island. While other newspapers either pandered to public opinion or wrote articles that added fuel to the storm of anti-Japanese sentiment, the Bainbridge Review was one of the few newspapers that always maintained an impartial viewpoint. In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment , there is an angry editorial about the time when an eviction order was posted on the island. "Despite the good behavior of the Japanese people since December 7, despite their recognized civil rights... despite the sense of justice that Americans have, there is no excuse for such a high-handed and short eviction order." Later, they also said: "We have said over and over again that this is unconstitutional. It's an affront... to the human rights protected by the Bill of Rights. (The reason we continued to write these editorials) was not because we had Japanese Americans, but because if this can happen to Japanese Americans, it can happen to German Americans, Chinese Americans, fat Americans, Americans who are in the Rotary Club, any American, anyone."

10. In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During the Internment , op. cit.

11. Dear Breed, cited above

Letters from the children to Clara Breed can also be found online at the Japanese American National Museum.

http://www.janm.org/collections/clara-breed-collection/

*Reprinted from the 133rd issue (April 2013) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett