Read Chapter 1 (2) >>

3. The attack on Pearl Harbor and its repercussions <December 7, 1941 – Spring 1942>

On Sunday, December 7, 1941 (Showa 16), many Japanese people living on the West Coast learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor through emergency radio news that was repeated incessantly: "The Japanese military has attacked Pearl Harbor. ... The damage to the American fleet is enormous. Fires are spreading all over the coast..." 1

The following is an excerpt from Breed's letter that appeared in an article in the Library Journal (June 1942) written by Los Angeles Library Children's Librarian Zeda Taylor:

Working in a community children's library for 14 years, I have had the opportunity to develop strong friendships with children. During that time, a boy of seven has grown into a young man of 21, and a girl of five into a young woman of 19. Having simply been by their side during that time, I feel an immense sense of pride in their strength, youth, and courage.

December 7th was a shock to everyone, but for Japanese children, it was the shock of their world coming crashing down on them.

Yoshiko's family heard about it on the radio when they were eating lunch after returning from church. The family was skeptical, and even if it was true, they thought it was just the work of a few fanatics, and they never imagined that it would lead to a war. In the afternoon, Yoshiko went to the library.

In truth, I was more preoccupied with my approaching final exams at university than with this strange news, so I went to the library to study. When I arrived, I found several groups of Nisei students anxiously discussing this shocking event. We all agreed that it was just a sudden event, and soon turned our attention back to our books. I thought nothing more of the Pearl Harbor attack and stayed in the library until 5 p.m.

When we returned home, the house was filled with an eerie silence. A strange man was sitting in the living room, and my father was nowhere to be seen. FBI agents had come and taken my father away, as had been the case with dozens of other Japanese people. … Finally, it was just my mother, my sister Keiko, and me. My mother prepared dinner, and we all sat down to eat, but no one felt like eating anything. Something had changed somewhere, without my father. No one dared to speak of the fear that was crouching in our hearts like a heavy black stone.

"Let's leave the balcony light on and the screen door unlatched, in case your father comes home late tonight," her mother said hopefully.

However , the next morning, the balcony light was still on and no one had any idea where my father was.

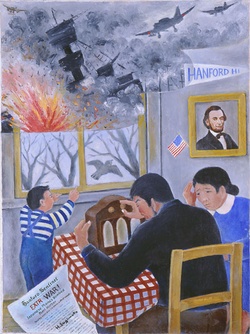

(Untitled by Henry Sugimoto. Gift of Madeleine Sugimoto and Naomi Tagawa. Collection of the Japanese American National Museum [92.97.105])

Henry also heard the news at home.

We heard the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor at around 3:00 p.m. At the time, my brother was into amateur radio, but I thought, "Oh no, I can't do that anymore." Soon after, Nobi Shigehara came running into the house and said, "They took you, Dad!" When we asked him, "What do you mean, they took you, Dad?" he said, "They came, arrested you, put you in a car and took you somewhere." When my father heard this, he hurriedly started packing his suitcase. Then the phone rang. It was George Sekiya, who was also an amateur radio operator like my brother, and he said, "They took everything. All my radio equipment. Everything I had." Then, exactly 15 minutes later, there was a knock on the front door. My brother's radio equipment had been taken, but fortunately my father was safe. 5

Federal agents wasted no time in arresting anyone who, like Yoshiko and Nobi's father, they thought had close ties to Japan: Japanese community leaders, Japanese language teachers, pastors, monks, newspaper reporters, people who worked for Japanese companies... Gene's father was one of them. Gene describes his feelings at the time:

On December 7, 1941, the war between Japan and the United States began. ... That night, early in the morning on December 8, two FBI agents came and arrested my father and took him away. A list of hundreds of Japanese American leaders living on the West Coast of the United States had been compiled, and my father's name was on it, and he was to be arrested within 24 hours of the outbreak of war. It was clear that the FBI was prepared and ready to act as soon as hostilities broke out. Neither my father nor anyone else had any criminal history. My father was arrested and taken into custody because he held a leadership position in the Japanese American community. For about two years after that, none of my family members were able to see my father.

I was asleep and didn't know about my father's arrest. In the morning, my older sister Hoshiko told me. She pointed to a telephone hanging on the kitchen wall. The FBI had cut the phone line before leaving, so that no one would know they had come. The fact that the FBI had cut the line had a stronger impact on me than my father's arrest. It was a concrete sign that the US government viewed us as enemies. For days, I stared blankly at the cut telephone line dangling from the kitchen wall. Until someone finally came and fixed it.

A few weeks later, I received a letter from my father. It was from the Santa Barbara County Jail. He later told me that he had been given only bread and water, and had been interrogated for several days. They all assumed that they would be executed. Although he didn't say so in the letter, it seemed that he had resigned himself to the fact that he would never see his family again. 6

Henry's new friend likes America and hopes that America will not go to war with Europe or Asia. The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, when he went to school, he told Henry with a serious face, "Lots of things are going to happen from now on." However, Henry, who was a junior high school student, did not understand the seriousness of the situation... 7

My new friend's prediction came true. Many things happened. The Issei had been living a stable life after all the hardships they had endured, but after the attack on Pearl Harbor, their lives changed drastically. First, the Issei's business licenses were revoked, and their bank deposits were frozen. The principal of the Japanese school was arrested, and the school was closed indefinitely. There were also incidents of violence against Japanese people. Soon after the new year, 26 Japanese staff members who were in charge of administration at a public elementary school in Seattle were forced to resign due to pressure from parents. Japanese people wearing red hats at train stations had suddenly become Filipinos. In California, 34 Japanese public servants were fired. Anger against Japan was directed at Japanese people. Japanese people volunteered for the U.S. military, bought defense bonds to support the war effort, and donated blood, but this had no effect on calming public opinion.

Far from calming the situation, it was the military, politicians, and the media that fanned the flames of war madness and public opinion. The newspapers continued to write rumors and speculation as if they were fact, and on December 15th, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox began to say completely false things, such as that Japanese Americans in Hawaii had helped Japan in the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, and that there was a large-scale spy ring among Japanese Americans. However, the Japanese community was quiet. There was no activity from this "large-scale spy ring." Well, since there was no organization, there couldn't be any action. Then, some people started to say, "The fact that there was no espionage activity by Japanese Americans living on the West Coast is proof that they were secretly planning the next surprise attack." Earl Warren, who was the District Attorney of California at the time, was one of those people. Secretary of War Stimson and the president were convinced by such arguments. This led to the forced eviction and internment of Japanese Americans.

There was also a high-ranking government official who opposed the forced eviction and internment of Japanese Americans. This was J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He said that since all Japanese Americans who seemed problematic had been imprisoned after the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was no need to evict or intern other Japanese Americans. He said that the forced eviction and internment were the result of succumbing to public opinion and political pressure, and were not based on actual data.8

On February 9 , a curfew was imposed on Japanese Americans on the West Coast from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m., but Henry walked home late at night from the nearby Yesler Library Branch. Just in case, he had a China badge that his Chinese friend Al had given him hidden in his trouser pocket. "A China badge is a round badge with a pattern around it and the word 'China' written in the middle. Al said that we were the same height and had similar faces, so if we got arrested, we could just show him the badge and he said we could use his name." 10

In mid-February, Principal Sears held an assembly for Japanese-American children. This is Henry's report on that occasion.

The principal was worried about us being harmed. He showed a proactive attitude to protect our safety by saying, "If anything happens on the way to or from school, please report it to me directly immediately." The curfew is from 8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m., so those who participate in club activities that start at 5:00 or 5:30 a.m. should talk to their advisor and ask to change the time. He also said, "No matter what happens, I will keep a proper record of your activities so that you can continue your studies in the future." Looking back, it seems that the principal was foreseeing the future. But at the time, it was like preaching to choirs. As soon as his words reached our ears, they didn't get through to us, and just bounced off of us. Soon after this rally, a presidential executive order was issued... 11

Presidential Executive Order 9066

"We will never, under any threat or danger, renounce the liberties our fathers established in the Bill of Rights," said President Roosevelt in a loud speech at the 150th anniversary ceremony of the Bill of Rights, just one week after the attack on Pearl Harbor. However, about two months later, on February 19, 1942, he signed Executive Order 9066, which gave the military "the authority to isolate civilians from any area without trial or interrogation." 12

This designated the West Coast as a military zone, and gave the Department of War and Lieutenant General John DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Command, the authority to evict Japanese Americans if it was necessary for military purposes. Lieutenant DeWitt had long believed that if there was a war with Japan, there was a good chance that Japanese Americans on the West Coast would help Japan. Even the Manson Report did not change his mind.

The Army then took power and evicted over 110,000 people from their homes and transported them without telling them where they were going because they might not be loyal to them. Not one of them had ever been tried or convicted of a crime. Although 70 percent were American citizens, their civil rights were ignored. They were simply accused of a crime because of their Japanese blood.13

Testimony of Yoshio Nakamura 14

My history teacher told me not to worry, Yoshio, you're an American. The U.S. Constitution doesn't allow for forced relocation. When I told him the following week that the order had been issued, he was stunned.

Notes:

1. Yoshimichi Nagae, "The Dawn of the Japanese-Americans: Testimony of First Generation American Journalist Shichinosuke Asano," Iwate Nippo Press, 1987

2. See War Children on the Pacific: A Symposium Article, op. cit.

3. "Dear Breed" (see above)

4. See above, "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of a Japanese-American Family During Wartime."

5. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

6. See above, "Torn Identity: The Life of a Japanese-American Journalist"

7. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

8. Takami, David A. Divided Destiny: A History of Japanese Americans in Seattle . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009.

9. Henry says February here, but I think it's more appropriate to assume that the Seattle curfew was imposed on March 2nd, when Lt. John DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Command, issued the first proclamation, which designated the western half of California, Washington, and Oregon, and part of Arizona, as military zones and imposed a curfew from 8pm to 6am within those zones. This proclamation also encouraged voluntary movement out of military zones. Lt. DeWitt issued a stricter curfew on March 24th. This is based on an interview, so I'll leave it as Henry said.

10. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

As for the China badge, reactions vary depending on the person, their age, and their relationship to the person wearing the badge, with some saying they were "hurt" (Takezawa Yasuko, "Japanese American Ethnicity") and others saying, "...I was extremely infuriated by the fact that it emphasized that I was not Japanese" (Ito Kazuo, "80 Years of American Spring and Autumn - A Commemorative Book for the 30th Anniversary of the Founding of Seattle Japanese Community").

11. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

12. Densho (Tradition): Based on the Japanese American Legacy Project’s U.S.-Japan Timeline.

13. Dear Breed, cited above

14. Testimony at a nationwide hearing conducted by the Commission on Wartime Civilian Relocation and Internment (CWRIC) in 1981.

CWRIC Testimony of Yoshio Nakamura, Los Angeles, Aug. 6, 1981

Previously mentioned, "Dear Breed"

*Reprinted from the 133rd issue (April 2013) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett