Read Part 2 >>

The Small Altars of Heart Mountain Relocation Center

At least six small Buddhist altars were built at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center for personal home use. The Bishop Obutsudan (Figure 10) was the last to be built and was made with fine wood. The others (whose construction dates are unknown) were made from scrap lumber, very likely leftover materials in the Heart Mountain Center Carpenter Shop. Except for one, the other altars have been painted in opaque colors; the exceptional one has a clear finish, which displays the quality of scraps that were used.

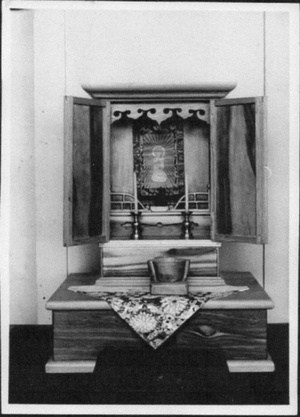

The Bishop Obutsudan

Ryotai Matsukage, the bishop of the Buddhist Churches of America, had the altar shown in Figure 10 made for his personal home use. Because the headquarters of the Buddhist Churches of America1 was located in San Francisco, Bishop Matsukage was relocated to the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah.

This obutsudan was built by Shinzaburo and Gentaro Nishiura at the Heart Mountain Center; on completion, it was shipped to Topaz. In a letter to Shinzaburo – dated June 27, 1945, and written in kanji – the bishop made payment of $47.00 for the obutsudan.2 The approximate dimensions are 20 inches wide, 32 inches tall, and 14 inches deep. The top of the altar is gracefully curved, requiring a steaming of the wood. The wood used and the finish are of the same quality as the large Aso and Shibata Obutsudans. The Bishop Obutsudan features finely carved columns and panels, one of which is at the top of the exterior. An interior detail that is not visible in Figure 10 is a hint of a temple roof. The base has a drawer with a classical hand-carved pull. On each door is a perfectly carved sagari fuji mon, a feature shared with the Aso and Shibata Obutsudans. The many details show skilled craftsmanship.

The Topaz Center closed on October 30, 1945. The headquarters of the Buddhist Churches of America and the bishop returned to San Francisco; the obutsudan went with him. Reverend Shintatsu Sanada cared for the bishop through his final years of illness, and when the bishop passed away in 1948 without any heirs, the ownership of the obutsudan passed to Reverend Sanada. Later, ownership passed to Reverend Sanada’s son, and remains in his posession.3

The Kimoto Butsudan

According to Alice Kimoto Ibaraki of Los Angeles, the present owner, the Kimoto Butsudan (Figures 11a and 11b) was made by the same builders as the Kubose Shumidan – that is, Suetsuna Okashima and Naoki Wakaye. The butsudan was made for Alice’s father, Kinzuchi Kimoto, who took it with him to Los Angeles when he returned in June 1945.

In July 1945, Okashima returned to San Jose to operate a strawberry farm, and, in October 1945, Wakaye returned to San Francisco – it is not known whether he continued to work as a skilled carpenter.

The right door in the closed-door image (Figure 11b) is slightly ajar and the interior is visible. The doors are curved (Figure 11a), which required steaming, and appear to be made of fine wood; the remaining parts appear to be ordinary wood, perhaps scraps. The doors are the work of skilled craftsmen. The dimensions are approximately 18 inches tall, 12 inches wide, and 8 inches deep.4

The Chikuma Butsudan

Masaki Chikuma, who worked in the Heart Mountain Cabinet Shop, collected leftover lumber and had Shinzaburo and Gentaro Nishiura build a home altar with the lumber. As Figure 12 shows, the wood was of good quality, requiring only a clear finish. The dimensions are 22 inches tall, 11 inches wide, and 8 inches deep.5 The butsudan also has the added feature of a drawer in the base with a hand-made classical pull.

Chikuma may have been assigned to the Cabinet Shop, but his pre-Relocation work was as a farmer in Santa Clara, California. Archival records about the Heart Mountain Relocation Center show that most people employed as carpenters were not formerly employed in building and construction trades. It is unlikely that Chikuma was involved in the actual building of his butsudan. He returned to Santa Clara in March 1945 to resume farming. The butsudan is now owned by his son, George Chikuma.

The Nishiura Butsudan

Shinzaburo and Gentaro Nishiura built the Nishiura Butsudan for their personal use (Figure 13a). Its dimensions are 34 ¼ inches tall, 24 inches wide, and 17 inches deep.6 This butsudan has many elaborate features of the Shibata Obutsudan, such as two sets of folding doors, one interior and one to close the butsudan, and a temple roof. The craftsmen could not achieve this design by merely shrinking the dimensions of the Shibata Obutsudan, for that would make the shrine area too small to place objects in. Instead, they reduced the temple roof to just the underside, as can be seen in Figure 13b. The carved top panel of the Shibata Obutsudan has been changed to a very simple screen design. The black paint used as trim emphasizes the bright color of the shrine area. To add height to the altar, two drawers with traditional pull handles were added under the shrine area. This altar demonstrates the skill of these artisans; to quote Kiyoshi Nishiura,7 “Shinzaburo was a sharp mathematical whiz, Gentaro was more ‘sublime.’”

The years 1942-1945 were creative ones for the Nishiura brothers, and their creations helped Buddhists and the Buddhist churches sustain their religion far from their West Coast origins. In late September 1945, Shinzaburo returned to Mountain View. Earlier, in August 1945, Gentaro had relocated to Denver to join his son, Kiyoshi, so that they could return together to San Jose. The three men restarted the Nishiura Construction Company in October of that year. The Nishiura Butsudan followed them from Heart Mountain to California. The ownership of the butsudan was passed to Kiyoshi on the death of the brothers, then to Kiyoshi’s wife, Stella, on his death, and finally to Anne, daughter of Kiyoshi and Stella.

The Dobashi Butsudan

The provenance of this butsudan is somewhat murky. The Dobashi family was a large and prominent San Jose family before 1941. There is no record confirming that they requested that a butsudan be built for them, and the members of the Nishiura family who would know the history of the altar’s construction are now deceased. The butsudan may have been on loan to the Dobashi family. In 2010 the Dobashi family asked Stella Nishiura to take the butsudan.

The altar is approximately 38 inches tall, 24 inches wide, and 20 inches deep.8 The material used is scrap lumber, and the finish is in the style of the Nishiura Butsudan. Unlike the Bishop Obutsudan and the Chikuma and Nishiura Butsudans, there are no drawers at the bottom of this altar.

The Ishigo Butsudan

The existence of this altar (Figure 15) has been documented by Estelle Ishigo and will therefore be called the Ishigo Butsudan, although it was not made for her. Its whereabouts are not known. Ishigo donated a photo of it to the University of California at Los Angeles Library.9 The maker and the dimensions of the altar are not recorded. The only relevant recorded information is that the altar was made in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center.

Estelle Ishigo was not a person of Japanese ancestry, but she was married to Arthur Shigeharu Ishigo, who was born in San Francisco. Arthur had to relocate, and she went with him to Heart Mountain even though she could have chosen not to.10 Only U.S. citizens were eligible to be on supervisory committees in the Relocation centers. Estelle was on the committee that supervised the arts and crafts activities of the Heart Mountain Center. Furthermore, she was given “authority to visit all parts of the Center and depict any phase of camp life (except those under control of the U.S. Army), which she has been directed to paint or sketch.”11 Some of her work was published in 1972 [Ishigo], but not as a government archival record.

Notes: (*The references occur at the end of the fourth part.)

- The history of the Buddhist Churches of America has been documented in BCA beginning on page 43. The Buddhist Churches of America was legally incorporated in 1944 as a California organization (interestingly, this was during the years of the Relocation). Prior to its official incorporation the Church had “evolve into a missionary branch of the Hompa Hongwanji Headquartered in Kyoto, Japan.” This evolution had its controversies – especially being headquartered in Kyoto during World War II. At its headquarters in the Topaz Center, the newly incorporated church appointed Ryotai Matsukage as bishop. Recollections of the incorporation can be found in Masuyama. The events surrounding the incorporation were reported by the Topaz Relocation Center Newspaper: Topaz Times, Semi-weekly, Vol. III, No. 9, Topaz, Utah, Saturday, April 29, 1944, page 5, and Vol. III, No. Buddhist Altars and Poetry 24 10, May 3, 1944, page 3. It is interesting to note that the incorporation papers were signed only by U.S. citizens; implicit was the emphasis on “America” in the name of the newly formed organization. Added on January 2015: The November 4, 1944, issue of the Heart Mountain Sentinel (Vol. III, No. 45, page 3) reported on a tea party given for Bishop Matsukage. His trip from Topaz Relocation Center occurred after the incorporation of the Buddhist Churches of America and the dedication of the Shibata Obutsudan. It is very likely that, during this trip, the bishop had seen the Aso and Shibata Obutsudans, met the Nishiura brothers, and requested that a small altar be made for him.

- The letter is in the Nishiura Archives.

- In a note written by Shinzui Sanada to the author, the provenance of the obutsudan was detailed. As the bishop had no heirs, the bishop’s estate passed the ownership of the obutsudan to Reverend Shintatsu Sanada. On the death of Reverend Sanada the ownership of the obutsudan passed to his son Shinzui Sanada.

- Dimensions were provided by Irene Eiko Masuyama.

- Dimensions were provided by Alfred Nishiura, nephew-in-law of George Chikuma.

- Dimensions were provided by Alfred Nishiura.

- Naomi Hirahara attributes this quote to Kiyoshi Nishiura, son of Gentaro Nishiura, from a December 1998 Japanese American National Museum interview. See Hirahara.

- Dimensions provided by the author.

- Calisphere, California Digital Library, UC Libraries. http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu, listed under the title: Buddhist shrine.

- See Ishigo, page vi.

- See Ishigo, page v.

© 2015 Togo Nishiura