One dark night when I was living alone in my twenties, my mother phoned me at one a.m. to tell me to turn on the television.

“Susan. Go turn on channel eleven. Right now.” Blinking, bleary, I imagined ambulances, disasters, twisted cars steaming at the side of the highway. But it was none of that.

“What is it?” When I understood that nobody in our family was near death, I felt grouchy. My eyeslashes were gummy, stuck together, and the inside of my mouth was foul. Sleep beckoned from the other side of my pillow.

“It’s Daddy’s movie. Go for Broke.”

I rubbed my hand over my face. “Oh! Have I missed much?”

“It only started about ten minutes ago. Daddy opened a new bag of arare so we can have a snack while we watch. Too bad you can’t come over, middle of the night, neh?” I could hear the wishing in her voice. I was an hour away, my Bronx apartment to their New Jersey house.

“No, Mom, thanks. I’ll watch from here.” I pulled the quilt around my body. The irritation had melted away. “Thanks for calling.” I got up to put on hot water for tea and to settle in front of my little TV set.

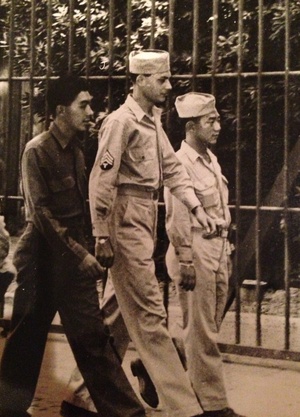

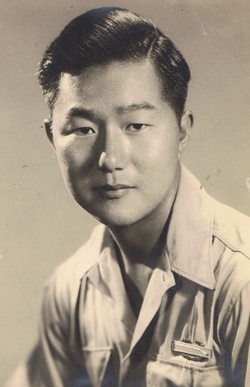

Go for Broke. The old black and white movie starring Van Johnson and the largest cast of Asian actors I’d ever seen on a screen. The World War II movie usually only aired once a year and it was our family tradition to keep a vigilant eye on the newspaper listings. It only usually appeared during the Late-Late-Late-Movie or in the middle of the afternoon, midweek. This was decades before the onslaught of seven-hundred channels, twenty-four hours a day programming. Once my parents even let me come home from school at lunchtime so I could watch it.

Four four two. Those magic numbers. Hero numbers. How I loved that story, loved seeing the Nisei soldiers, short and fast like my dad, how they tricked the Germans and saved the Lost Battalion in France. I loved their inside jokes, the sprinkling of Japanese words that I recognized. Their password was bakatare, Japanese for stupid idiot. It was like hearing a secret swear word, something that only we knew about. This movie made the war seem bloodless and exciting, even a little bit funny. It made my father victorious.

When I was small, he used to tell me that the 442nd was “the most decorated unit in US history.” Because they were so brave, he said, they got to wear the most medals. Beautiful, shining decorations on their uniforms like purple hearts, ribbons, stars. I imagined my father bejeweled and shimmering like a Christmas tree.

I didn’t understand, for a long time, that most decorated really meant the most dead, most hurt, least likely to ever return home. In Go for Broke, the famous battle to free the Lost Battalion looks like a glorious run through the forest, an obstacle course of leaping over logs, the soldiers grinning and whooping as they charge uphill. The ones who are shot twirl in midair and collapse to the ground quietly. There is no blood, no infested wounds, no shards of bone glistening through skin. I used to jump on the couch during this scene, throwing pillows and rice crackers in the air. I chanted, “Go for broke! Go for broke!” In the final scene, when the American flag is fluttering, when FDR is awarding medals to the soldiers, I stood in front of my father and saluted. I tore newspaper into tiny bits and let it rain down on his head.

This was one of our family’s favorite and most secret rituals. We never knew when to expect it, but when it came, all normal rules were suspended and we got to celebrate the hero in our house.

My father surely knew that it wasn’t like that. Not for real. I wondered if when he watched those scenes, his memory was superimposed with a layer of blood, of screams and cries that only he could hear. But he liked to present it to us, my mother and I, in the Hollywood way, the version that has us cheering and throwing confetti. He told us, with pride, of the hundred-pound radio he carried on his back, when he weighed not much more himself. How he lived and fought in Italy for two years, alongside his brothers, my uncles.

That morning in my twenties, I watched quietly, a mug of green tea in my hands. It had been at least five years since I’d seen it, and the first time I’d ever watched it alone. This time, I flinched every time I heard the word “Jap.” Good old Japs. At the film’s end, the men of the Lost Battalion are passing by the 442nd, shaking their hands and thanking them for their lives. One of the tall, light skinned soldiers reaches out to the Nisei soldier who’s from Honolulu. “Aloha, little guy,” he says, and he wiggles the man’s nose. As if he were a child, or a pet.

Why had I never noticed this before? I got up and flung the tea mug into the sink so hard that the handle snapped off. I started crying as the patriotic music played over the credits. The movie was over. I faced the west wall, towards New Jersey, where my father was sitting on the living room sofa in his bathrobe. I raised my fingers up to my hair in salute.

* * * * *

My father died at eighty-one in May of 2000, during a surgery to repair an aneurism in his abdominal aorta. The funeral was held on the Friday of Memorial Day weekend. When we went to the mortuary and spoke with the elderly director, he scribbled notes about my father on a clipboard. “Was he a veteran?” he asked. Oh yes, I said. He was a World War II veteran, a member of the Japanese American 442nd Regiment. It was one of the things in his life of which he was most proud.

The funeral director put down his pen and dabbed at his eyes. “I’m honored,” he said. “I’m honored to have one of those heroes here in my own home.” He arranged for military representatives to present a perfectly folded flag to my mother, as a handful of my father’s 442nd comrades stood around her. The entire funeral home was bedecked in flags and red, white, and blue banners. So was the rest of the neighborhood, the whole town. I know that it was for Memorial Day, but I believed in my heart that every flag was really for him.

This year, my mother received a small but weighty package in the mail. It contained a black box with United States Mint imprinted in gold lettering on the cover. Inside, a square black velvet box. She opened it and inside was a solid gold disc that covered her whole palm. One side depicted uniformed soldiers in profile, under an arc of words that said, NISEI SOLDIERS OF WORLD WAR II: GO FOR BROKE.

We took it out and felt its heft. A serious piece of gold. The back side was imprinted with the insignias of the Military Intelligence Service, the familiar held-aloft torch of the 442nd, and the 100th Infantry Battalion. On the bottom: Act of Congress 2010.

The enclosed letter stated that my father had been posthumously awarded this Congressional Gold Medal by President Obama’s Public Law 111-254, in recognition for his unit’s collective bravery and valor.

The United States remains forever indebted to the bravery, valor, and dedication to country these men faced while fighting a 2-fronted battle of discrimination at home and fascism abroad.

It took us a while to realize what we were looking at. It had arrived late, much too late for him to appreciate, but I can imagine him turning it over and over in his hands, nodding, feeling its dense weight, seeing it gleam in the sunlight.

“He would have liked this,” my mother murmured. She is ninety now. Once or twice a week I see her remove the lid from the pink outer box, and lift the black case from its bubble wrap. She opens the cover and the disc inside always seems to take her by surprise, as it does with me. She reads the letter, running her finger along my father’s underlined name, and then folds it up and puts it back in the envelope. Yes. He would have liked it very much.

* This article was originally published on Medium.com on November 11, 2013.

© 2015 Susan Ito