The other day, after the school lesson was over,

I headed to a bakery I'd never been to before.

I took a bus and walked using a map app.

It took nearly an hour to get there.My dream is to have my own bakery.

From next spring,

I plan to begin my training at a local bakery.

During this preparation period,

These days, I visit many bakeries.

I'm researching to see if I can find anything.Going to a store far away

It can be tough for students with limited means of transportation (and money to spend), and to be honest, it's quite difficult.But under the blazing sun,

As I walked down the street I felt free.

I think that being able to walk on your own two feet and move forward in the direction of what you love is proof of freedom.

When I read Yamaguchi Satsuki's bouncy feelings in "Today's Darling" in the daily Itoi Shimbun, I knew this was exactly what I was looking for. When I asked people who spent their childhood in the camps what life was like for the children in the camps, many of them said "it was fun." At first glance, it may seem carefree and fun, but the freedom within the barbed wire enclosure is fundamentally different from the true freedom of "being able to walk on your own two feet, in the direction of what you love." I came across Yamaguchi's writing when I felt frustrated that I was not able to fully convey this. By comparing the writings of the children in the camps with Yamaguchi's writing, I was able to see the differences and think about the importance of protecting a society in which anyone can "walk on their own two feet, in the direction of what they love." With the permission of Yamaguchi Satsuki and the daily Itoi Shimbun, I have published this article.

Viktor Frankl said, "You can throw a man into a concentration camp and take away everything he has, but you can never take away his final human freedom: how to behave in the environment he is given." 2 Let us continue with the story of a Japanese-American who, in a concentration camp, dreamed of a society in which everyone could "walk on their own two feet, moving towards what they love," proving Frankl's words.

* * * * *

1. 1943 (continued from Chapter 3)

Three Tons of Books as a Gift - Spring

In the spring of 1943, three tons of books arrived at Minidoka. They were surplus books from the Victory Book Campaign. In the diary of Director Kleinkopf on May 18, he wrote, "The three tons of books that had been in the warehouse have finally been put on the shelves of the Community English Library and are now available for viewing. Most of them are donated books, and there are multiple copies of the same book, and some are so old that they are worthless. " How many books are in three tons? Assuming each book weighs 500 grams, that would be about 6,000 books.

These large volumes of books were collected as part of a large-scale book collection campaign called the Victory Book Campaign, organized by the American Library Association to send books to soldiers and prisoners of war, whose numbers had increased dramatically during the war. Not only the media, but also dry cleaners put flyers about the campaign in the bags of clothes returned to customers, factories placed book collection boxes in their work areas, and supermarket trucks and highway patrol officers helped to transport the collected books, making it a truly nationwide book collection effort. 4 According to a survey by the four military services, the books most desired by soldiers were recent bestsellers and novels published in the past ten years, with adventure novels, westerns, detective novels, and mystery novels being particularly popular, as well as specialized books on architecture, aviation, and other subjects. Paperbacks, which were easy to carry and could be taken to the battlefield, were particularly popular. 5 By June 1942, the target of 10 million books had been collected. Approximately half of the books, excluding those in poor condition, were sent to military institutions.

Large quantities of surplus books from this campaign were delivered to each internment camp. However, all of these books were written in English. Japanese books were also absolutely necessary for the Issei and Kibei Nisei. Next, let's look at the case of Topaz Internment Camp, where, even within the camp that adhered to the American assimilationist ideology, efforts were made to establish a Japanese language library, preaching the need for a Japanese cultural space.

Movement towards establishing a Japanese language library

At the Topaz Internment Camp, there was a man who thought about creating a Japanese language library using the Japanese books that had been confiscated at the temporary camp. His name was Asano Shichinosuke6 . Asano's biography, Nagae Yoshimichi, described the conditions at the camp as follows:

At the time of their arrival, life for the Japanese was chaotic, with no order, no motivation to live, and they were simply in a state of despair. Furthermore, rumors and speculation were spread among the residents, and anxiety and confusion swirled throughout the relocation site. The only solace was listening to shortwave radio broadcasts of Japan, and spending each day listening to the Imperial General Headquarters' announcements of victory. As a result, ultranationalists began to rear their heads within the site, striding down the main streets as if to say, "Japan is winning, just wait and see, our time is coming," and they opposed the relocation administration office, branding all those who were communicating between the authorities and the residents as spies, and there was a constant stream of people committing foolish acts such as assaulting and sabotaging operations .

In order to overcome this situation, Kyogoku Itsuzo, who was the chairman of the Adult Education Committee, proposed that several experts meet to discuss countermeasures. Asano immediately proposed the establishment of a Japanese language library. At the time, there were 2,400 Issei and 800 Nisei who had returned to America in the Topaz Camp. Asano felt that a Japanese language library would be a place to promote healthy spiritual and emotional exchange, and that literary books would soothe the residents' hardened hearts and bring them comfort, philosophical and religious books would give them a perspective on life, and scientific books would no doubt cultivate a scientific mind. 10 This proposal was supported by the chairman and several others, and the chairman immediately began negotiations with the Administration, but the Administration, which was wholeheartedly in support of the plan to Americanize the camp, was not enthusiastic about the establishment of a Japanese language library. However, in the winter of 1942, riots broke out in Poston and Manzanar (Issue No. 135), and with the idea that a Japanese library could be of some use in preventing such incidents, permission was given to lend Japanese books in a corner of the English library on January 19, 1943. The condition was that a budget would be provided for one librarian to handle Japanese books, but that the library would have to obtain its own books and operating funds.

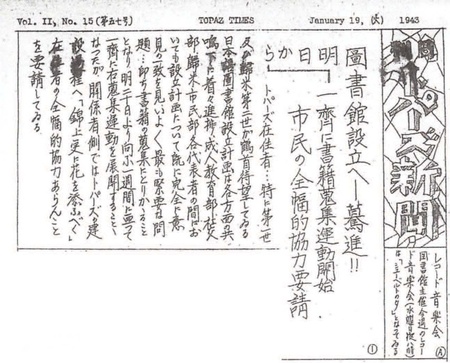

Nevertheless, Asano was overjoyed with this permission and immediately appealed for the cooperation of the detainees in the January 19th edition of the Daily Topaz newspaper, the newspaper within the camp, stating, "The library will be established from tomorrow - moving forward at full speed! We will begin the book collection campaign all at once, and we request the full cooperation of the citizens," and "This will add an extra touch of beauty to the occasion." This article was written by Asano himself, and we hope that you will enjoy the spirit of this spirited generation. In the February 5th edition of the same paper, just before the opening, he expressed his gratitude for the support from the detainees in an article entitled, "The Japanese Library has finally been established, and the grand opening ceremony will be held the day after tomorrow." 11

(Credit: Densho Digital Archive)

This Japanese book corner was especially popular with the Issei, the Kibei Nisei, and the Nisei from Hawaii, whose Japanese language skills were better than those of the mainland Nisei. People craving books flocked to the library, and when it first opened, there were so many books that outside lending had to be temporarily stopped in order to meet the demand. In order to raise funds to repair equipment and books, lending was limited to those who paid or who had donated books, so many Issei stayed in the library to read. Kyogoku ordered 600 of his own books, which he had left at the International House of the University of California, Berkeley, at his own expense, to donate. The Topaz Newspaper of April 13th carried a breakdown of the books Kyogoku had donated under the headline "Luxurious books long awaited by readers have arrived." The collection includes the Complete Works of Meiji and Taisho Literature (50 volumes), the Complete Works of World Literature (40 volumes), the Complete Works of Modern Japanese Literature (50 volumes), the Complete Works of World Great Thought (30 volumes), the Complete Works of World Art (50 volumes), the Asahi Common Knowledge Lectures (10 volumes), the Complete Works of Self-Cultivation (12 volumes), the Complete Works of Natsume Soseki (12 volumes), the Complete Works of Tokutomi Roka, the Encyclopedia of the Japanese Home (3 volumes), the National Translation of the Buddhist Canon, the National Translation of the Tripitaka (100 volumes), and other books on religion, philosophy, history, literature, and popular topics, all of which are valuable and hard to find in America.

As the Japanese library stock grew, it became possible to lend books for free, but the next problem was finding a space. Asano felt that the Japanese library needed its own space, not just a corner of the English library. One reason was that he wanted to create a Japanese cultural space where the first generation of Japanese people, born in the Meiji period, who were used to reading aloud, could read aloud, talk freely, and hold exhibitions of flowers and crafts. Another reason was that he wanted to keep the Japanese library open for long hours without being bound by the English library's opening hours. On May 6, the Japanese library was given half of the recreation hall in Block 40, and became independent. For three days, the move was celebrated with an exhibition of shell crafts, and opening hours were extended from 10am to 10pm.

In his later years, Asano said, "The reason there weren't many problems at Topaz Camp was because of the Japanese language library," and "Everyone was absorbed in reading... they stayed up all night reading books." 13 The Issei, born in the Meiji era, were determined to do what they thought was necessary.

Notes:

1. From the August 3, 2013 issue of "Today's Darling" in the Daily Itoi Shimbun

http://www.1101.com/home.html

Yamaguchi apparently sent this email after reading Shigesato Itoi's article in "Today's Darling," in which he said, "I want to cherish freedom." After introducing Yamaguchi's email, Shigesato Itoi continued, "If she ever opens her own bakery, I'd love to know about it. I'd like to take the train and bus and go there next time."

2. "Man's Search for Meaning" by Viktor E. Frankl, translated by Kayoko Ikeda, Misuzu Shobo, 2002

3. Kleinkopt, Arthur. Relocation Center Diary 1942-1946 , Hagerman: Minidoka Internment National Monument, 2003.

4. Becker, Patti Clayton. Up the Hill of Opportunity: American Public Libraries and ALA During World War II , PhD Thesis, Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002.

5. Books Join the Battle: The Victory Book Campaign from Life on the Home Front, Oregon Responds to World War II

http://arcweb.sos.state.or.us/pages/exhibits/ww2/services/books.htm

6. Asano was born in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture in 1894. Before moving to the U.S., he was a student of Hara Takashi. In America, he worked as a journalist throughout his life, fighting against discrimination against Japanese Americans and contributing to the Japanese American community.

7. Shortly after the Japanese moved to their "relocation addresses," the Relocation Bureau decided to refer to the internees as evacuees and residents. In his diary dated December 31, 1942, Kleinkopf, the Superintendent of Minidoka Camp, wrote, "Today, I received a message from the Relocation Bureau staff, instructing government officials not to use the word Kow-Cajun (white person) but to call the person in charge. They were concerned that words like Kow-Cajun and Oriental (Asian person) could cause racial conflict and resentment. In this message, they also instructed us to call the Japanese 'evacuees' or 'residents.'"

8. Yoshimichi Nagae, "The Dawn of the Japanese-Americans: Testimony of the First Generation American Journalist Shichinosuke Asano," Iwate Nippo Press, 1987

9. Andrew Wertheimer, "Creating Cultural Space in an American Internment Camp: Asano Shichinosuke and the Topaz Japanese Library 1943-1945," Journal of the Japan Society for Library and Information Science 54(1), 1-15, 2008-03-31

10. See above, "The Dawn of Japanese Americans: Testimony by First-Generation Journalist Asano Nananosuke"

11. Topaz Times , Vol. II, No. 15, January 19, 1943.

Topaz Times , Vol. II, No. 30, February 5, 1943.

12. Topaz Times , Vol. III, No. 7, April 13, 1943.

13. See above, "The Dawn of Japanese Americans: Testimony by First-Generation Journalist Asano Nananosuke"

*Reprinted from the 136th issue (February 2014) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2014 Yuri Brockett