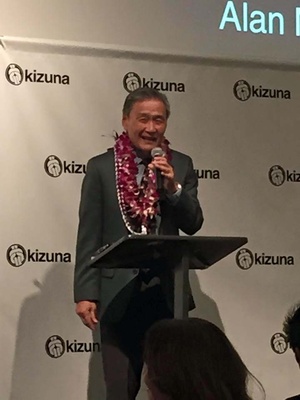

The smiling gentleman being roasted at the sold-out event to raise money for the youth-empowering program, Kizuna, was hardly the young radical who thirty-five years ago could have been mistaken for the sword-carrying D’Artagnan in the battle for redress. In the spirit of the roast, Chris Aihara, one of his Musketeers from that bygone era, gleefully informed the audience that Alan Nishio possessed “superior powers, keen intellect, relative good looks, and better than average athletic ability,” but was still “deeply flawed.”

As the laughter subsided, it was clear that the man on stage would agree he was no swashbuckling hero. Those who have worked with him throughout his nearly 50 years of community service would probably more aptly call him an undercover hero.

Quietly yet boldly, Alan has made his imprint on the Japanese American community in Los Angeles by staying in the shadows. As Sansei co-chair of the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations (NCRR) in the 1980s, he led by asking the Nisei to do the talking while he sat doing what he does best: listening, compromising, and strategizing. Meanwhile, Bert Nakano, an articulate Nisei camp survivor who worked for Pan Am, became NCRR’s spokesperson in part because, as Alan and others recognized, Bert had just enough anger to ignite other Nisei, and he worked for an airline that gave its employees free airfare. Knowing a lot of travel would be required for meetings, the cash-strapped founders were not dummies.

Alan fondly remembers that time in our community’s not so recent past when everything came together to make the impossible happen. He calls it a testament to our Japanese American-ness that many diverse groups and individuals with just as many differing opinions and approaches could work together to win something as elusive as redress. Though some groups would like to take all the credit, the Great Negotiator Alan says no one group could have done it alone. It took someone like him not to let ego get in the way. In fact, never one to steal the spotlight, Alan was the kind of leader the community needed when internal friction had the potential to ruin everything.

“If the JACL had their druthers,” said the co-chair of the more populist group that insisted camp survivors participate by telling their stories, “there would have been hearings in Washington with a lot of experts and scholars testifying.” Instead, witnessing the testimonies of real people across the country that endured the devastating camp experience was the emotional catalyst that made a difference. Going to Washington, D.C., to lobby was another way Alan and NCRR fought the good fight—sometimes without the blessing of other groups and lawmakers. The trip that began as a few NCRR folks deciding to use their own money to vacation in D.C. subsequently became a huge history-changing event.

Besides his ability to bring diverse groups together, Alan also embodies humility with true Japanese American aplomb. Bill Watanabe, former executive director of the Little Tokyo Service Center, the social service organization Alan has chaired for fifteen of more than thirty years on its board, couldn’t help but chide him for his modesty, insisting Alan had “much to be modest about.” Another roaster, Kizuna’s Kristin Fukushima, explained that even though Alan describes himself as the “shyest man you’ll ever meet,” he was really “all about the attention.”

There are those who would probably insist that Alan was born with a picket sign in his hand, but it was not until he attended UC Berkeley that he found himself smack-dab on the picket line. Caught in the hotbed of the ’60s Free Speech Movement, Alan would say that he had no choice but to join the protest movement when demonstrations blocked classrooms forcing students to take a stand. His involvement even made him change his major from mathematics to political science.

In college he recalls another life-transforming experience. Never having spoken about his family’s incarceration with his parents, he had no idea what camp meant until he happened across a telling book in the college library. Strangely enough, Alan was born at Manzanar on the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki but didn’t really understand what any of that signified. In that defining moment, he realized what Japanese Americans had endured and kept silent for as many years as he had lived.

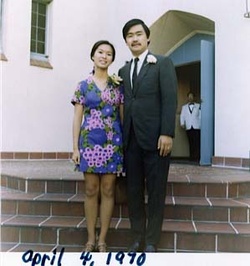

Between getting his B.A. and M.A., it still took him awhile to refine his sensibilities about community work. In the meantime, he gained some practical experience that taught him what hard work was all about. To help out his mother and sister after his father died and left them practically destitute, Alan took over his father’s gardening route. With absolutely no knowledge of pruning or planting, he covered his father’s full-time gardening job in a day and a half, leaving him time to continue his graduate studies at USC. Fortunately, his then girlfriend and now wife Yvonne stuck with him during those exhausting days and nights, though she would bemoan that a typical Saturday night date with Alan would be watching him fall asleep on the couch.

Alan’s real entry into community activism came in the late ’70s when a group of Sansei demanded rights for Little Tokyo’s senior housing population that was in danger of being displaced by Japan-based corporations. As president of the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization (LTPRO), he wet his feet in community activism while preparing himself for the longer and rockier road ahead. When LTPRO eventually shifted its emphasis into three areas of concern, Alan decided to go with one of its offshoots, the Los Angeles Community Coalition for Redress and Reparations, which was to become NCRR, and the rest, well, is history.

Alan’s mantra of “stand up for justice” has long been the driving force that got him to join organizations that serve the Nikkei community, and he always managed to rise to the top. Frequently falling into the position of “chair,” Alan would say it was because all these community-based nonprofit organizations had to have one. Others saw him step forward in this voluntary role because he was trusted and experienced. And to Alan’s credit, knowing the amount of time and dedication it required, few others would likely not be willing to assume the leadership role. As of today, Alan has served (to mention a few) as chairman of the board of the Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC) for fifteen years, member of the board of the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center (JACCC), member of the advisory council for Kizuna, and past president of the California Conference for Equality and Justice. He was also a founding member and chair of the California Japanese American Community Leadership Council, a statewide organization seeking to preserve California Japantowns.

Believe it or not, nearly eight years ago, he had a “real job” that in fact paid him money. As associate vice president for the Division of Student Services at Cal State University, Long Beach, he made money in spite of himself because he never once asked for a raise. For a man who clearly worked hard and capably for all his good fortune, Alan would credit Lady Luck for having a supportive and trusting university president who rewarded him well for the relationships Alan nurtured with students over the years.

These days, he’s as busy as ever—to the point that he’s forced to choose his causes wisely in order to make time for his wife Yvonne, two daughters, and six grandchildren. Citing three organizations that take up most of his energy, he puts LTSC near the top because of its advocacy for social services to those less fortunate. He also names JACCC for its preservation of community arts and culture, and Kizuna for its focus on building tomorrow’s communities and leaders.

Alan does his undercover work with generosity of time, money, and spirit that leaves even the most bighearted community activists dumbfounded. Even though the Kizuna fundraiser was supposed to be a roast, Chris Aihara and Bill Watanabe, both JA pillars in their own right, couldn’t help but sing Alan’s praises. Bill said LTSC would not be the agency it is today without Alan’s “leadership, wisdom, and direction.” Chris capped her roast by describing Alan as someone who doesn’t want to be the center of Japanese American history because, as he had said to her many times, “It’s the story of all of us and of all our contributions.”

Both young and old gravitate to a man who loves the community that clearly loves him back. As Kizuna’s 20-something executive director Craig Ishii would begrudgingly admit, “Alan has more friends under the age of 25 than I do.”

If there is a person who personifies the Three Musketeers’ motto of “All for One and One for All,” it is Alan Nishio.

© 2015 Sharon Yamato